Indian Polity

Uniform Civil Code- Promise of Equality, Challenge of Pluralism

This editorial is based on “Uttarakhand Governor returns UCC and religious conversion amendment Bills” which was published in The Hindu on 17/12/2025. The article brings into picture the states push towards adopting UCC to provide common personal laws. This comes into conflict with the religious freedom guaranteed under the constitution.

For Prelims:UCC,DPSP,Fundamental Rights,Triple Talaq,Muslim Personal Law Case,Secularism,Constitutional Morality

For Mains: Need for a uniform civil code, gender justices, personal laws

Uttarakhand Governor has returned the Uniform Civil Code and religious conversion amendment Bills, citing technical and punitive inconsistencies, requiring redrafting and fresh legislative approval. The Uniform Civil Code, envisioned under Article 44 of the Directive Principles of State Policy, seeks to replace diverse personal laws with a common set of civil laws governing marriage, divorce, inheritance, adoption, and succession. Rooted in the ideals of equality before law and gender justice, the UCC remains one of the most debated constitutional goals, owing to concerns related to religious freedom, cultural diversity, and federalism. Recent developments have revived this debate, underlining the need to assess whether the pursuit of uniformity strengthens constitutional values or risks undermining India’s pluralistic fabric.

What Necessitates the Adoption of a Uniform Civil Code in India?

- Advancing Gender Justice and Women’s Rights: Several personal laws continue to contain provisions that place women at a disadvantage in matters of inheritance, divorce, maintenance, guardianship, and adoption.

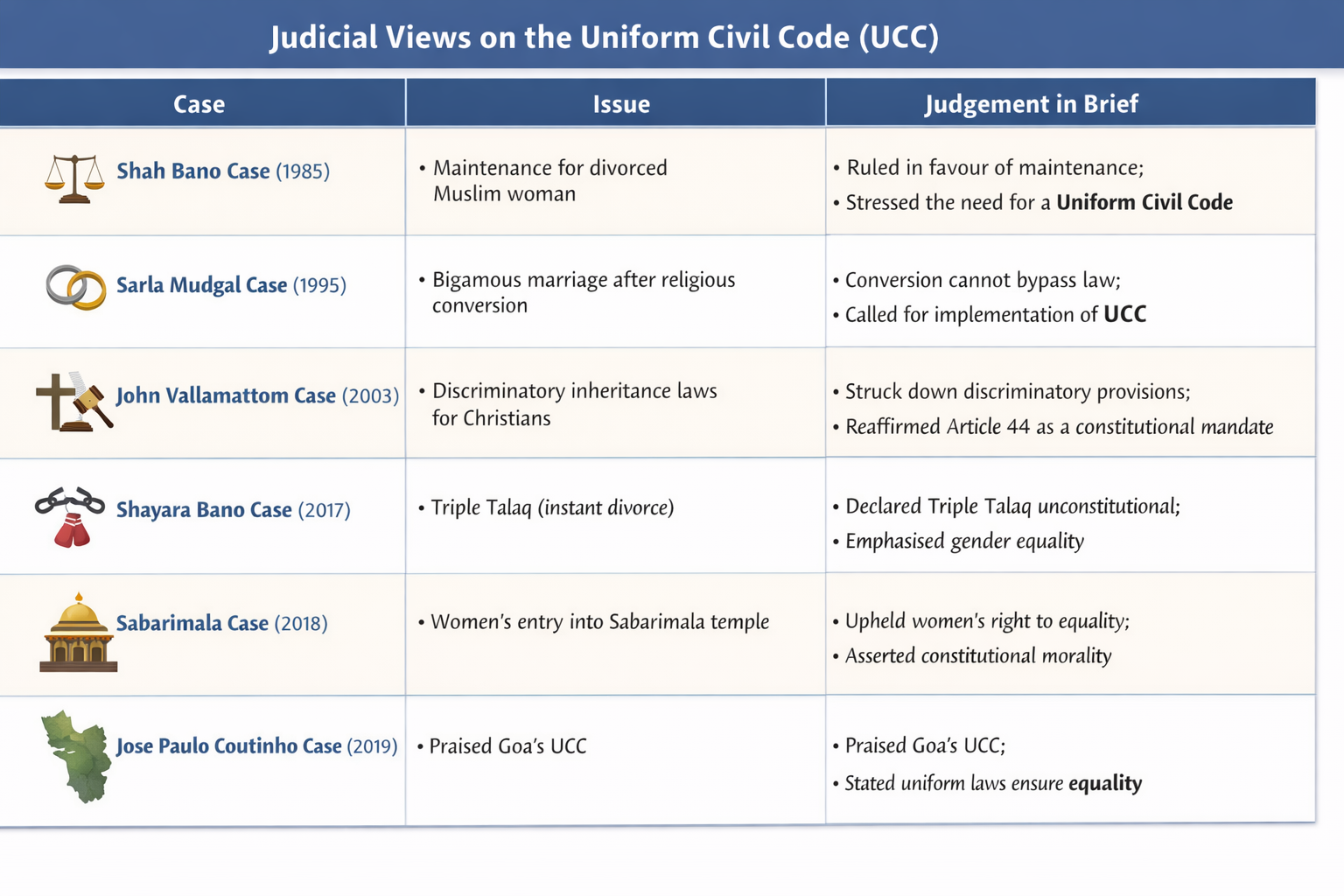

- For instance, practices such as unequal inheritance rights, unilateral divorce, or limited maintenance entitlements have historically affected women across communities. Judicial interventions, such as in the Shah Bano case (1985), have highlighted these inequities and the need for reform.

- A Uniform Civil Code can provide a gender-neutral legal framework, ensuring that civil rights flow from citizenship rather than religious identity.

- State-level codifications like Goa’s Civil Code illustrate how uniform personal laws can coexist with religious freedom while ensuring relatively equal rights for women.

- Upholding Equality Before Law: The coexistence of multiple personal laws leads to differential legal treatment of citizens based solely on religion or community, raising concerns under Article 14 of the Constitution.

- For example, individuals in similar civil situations, such as marriage dissolution or succession, are governed by different legal standards depending on their faith.

- A UCC seeks to establish uniform civil obligations and entitlements, reinforcing the constitutional principle that all citizens are equal before the law.

- The gradual harmonisation of laws through judicial interpretation, as seen in cases like Sarla Mudgal (1995), reflects this constitutional aspiration.

- Simplifying the Civil Justice System: India’s plural personal law regime adds significant complexity to the legal system, often resulting in lengthy litigation, conflicting interpretations, and jurisdictional confusion.

- Courts are required to interpret religious texts alongside statutory law, increasing the scope for ambiguity and inconsistency.

- There are currently over 950+ functional Family Courts across India. Despite their specialized nature, the volume of fresh filings (institutions) often outpaces disposals.

- A common civil code would streamline civil adjudication by providing a clear, secular, and codified set of rules, enhancing legal certainty and reducing judicial burden.

- The experience of States that have codified family laws, such as Goa, demonstrates how legal simplicity can improve accessibility and predictability for citizens.

- Courts are required to interpret religious texts alongside statutory law, increasing the scope for ambiguity and inconsistency.

- Reinforcing Constitutional Morality Over Social Practices: The UCC is rooted in the principle of constitutional morality, which requires that laws and governance be guided by the values enshrined in the Constitution rather than by discriminatory customs or social hierarchies.

- Certain traditional practices, even if culturally entrenched, may conflict with constitutional ideals of dignity, liberty, and equality.

- By prioritising individual rights and legal equality, a UCC seeks to align civil laws with constitutional values.

- The Supreme Court has repeatedly underscored that constitutional morality must prevail when social practices violate fundamental rights.

What are the Key Concerns in Implementing the Uniform Civil Code in India?

- Tension Between Religious Freedom and Cultural Autonomy: Personal laws in India are deeply intertwined with religious beliefs, rituals, and cultural identity. For many communities, matters such as marriage, inheritance, and succession are not merely legal arrangements but expressions of faith and tradition.

- A rigid or hastily imposed Uniform Civil Code may therefore be perceived as infringing upon the freedom of religion guaranteed under Article 25, which protects the right to profess, practise, and propagate religion, subject to public order, morality, and health.

- Judicial pronouncements, including observations in cases like Shirur Mutt (1954), have emphasised the need to respect essential religious practices, underscoring the constitutional sensitivity involved in reforming personal laws.

- Diversity of Customs Within and Across Communities: India’s social diversity extends far beyond differences between religions, significant variations exist within communities across regions, castes, and tribes.

- For instance, customary inheritance practices among tribal communities differ substantially from codified personal laws.

- While most of India follows a patrilineal inheritance system under the Hindu Succession Act, the Khasi, Jaintia, and Garo tribes of Meghalaya practice matriliny.

- Among the Khasis, ancestral property passes to the youngest daughter (Ka Khadduh), sharply contrasting with the largely patrilineal structure of codified Hindu law, where daughters gained equal inheritance rights only in 2005

- Since family and marriage fall under the Concurrent List, States have exercised flexibility in regulating them. While State-level initiatives like Goa’s civil code demonstrate the potential of decentralised reform, uneven adoption of the UCC raises concerns about balancing national uniformity with India’s federal and cultural diversity.

- A one-size-fits-all approach risks ignoring these social realities, leading to resistance and uneven implementation.

- For instance, customary inheritance practices among tribal communities differ substantially from codified personal laws.

- Perception of Majoritarian Bias and Minority Trust Deficit: One of the most persistent concerns surrounding the UCC is the fear that it may reflect the norms and practices of the majority community, thereby marginalising minority traditions.

- Past debates, including those following the Shah Bano case (1985), reveal how personal law reform can become politically polarising if not accompanied by consensus-building.

- In Pannalal Bansilal v. State of Andhra Pradesh (1996), the Supreme Court observed that the Uniform Civil Code should be implemented gradually and in a piecemeal manner, as social uniformity in personal laws cannot be imposed abruptly without consensus.

- If sections of society perceive the UCC as an instrument of cultural dominance rather than constitutional equality, it may erode trust and social cohesion. Hence, the legitimacy of the UCC depends critically on neutral drafting, inclusive consultation, and transparency.

- Past debates, including those following the Shah Bano case (1985), reveal how personal law reform can become politically polarising if not accompanied by consensus-building.

- Legal and Administrative Complexity:The sheer scale of consolidating thousands of uncodified and codified laws into a single framework presents a massive "legislative nightmare." India lacks a centralized database of all customary practices across its 700+ recognized tribes and various sub-sects.

- Beyond marriage and divorce, the UCC must address complex issues like taxation (e.g., the Hindu Undivided Family or HUF status), adoption, and maintenance.

- Scrapping the HUF status, for instance, would have significant implications for the revenue department and the financial planning of millions of citizens.

- Beyond marriage and divorce, the UCC must address complex issues like taxation (e.g., the Hindu Undivided Family or HUF status), adoption, and maintenance.

- Impact on LGBTQ+ Rights and Non-Binary Recognition:A major modern concern is whether the UCC will be truly "progressive" or just "uniform."Current personal laws are almost entirely binary, focusing on "husband" and "wife."

- There is a fear that the UCC might simply codify a "heteronormative" standard (one man, one woman) across all religions, thereby missing the opportunity to recognize same-sex marriages or non-binary gender identities.

- If the UCC is drafted based on "traditional family values" to gain political consensus, it might legally solidify the exclusion of the LGBTQ+ community for decades, making future reforms even harder.

What Should be the Roadmap for Effective Implementation of the Uniform Civil Code in India?

- Adopt a Phased, Incremental, and Consultative Reform Strategy: Rather than pursuing an abrupt or comprehensive overhaul, India should follow a phased approach to civil law reform. Initial efforts can focus on removing clearly discriminatory provisions, such as unequal inheritance rights or gender-biased divorce practices, across existing personal laws.

- This mirrors India’s own reform history, where gradual interventions (e.g., Hindu Code Bills of the 1950s) ensured social acceptance over time. Incremental reform reduces resistance and allows society and institutions to adapt.

- Prioritise Gender-Neutral Civil Laws Over Religion-Specific Uniformity: The core objective of the UCC should be gender justice, not cultural homogenisation. Reform should therefore centre on gender-neutral and rights-based civil laws applicable to all citizens, irrespective of religion.

- For example, the Supreme Court’s ruling in Shayara Bano (2017) demonstrates how targeted judicial intervention can eliminate gender discrimination without dismantling entire personal law systems.

- This approach ensures alignment with Articles 14 and 15 while minimising concerns over religious freedom.

- Institutionalise Broad Stakeholder Consultation and Social Dialogue: Successful reform requires inclusive consultation, particularly with women’s organisations, minority community representatives, legal experts, and civil society.

- Experiences from law reform commissions globally show that participatory law-making enhances legitimacy.

- In India, the Law Commission’s consultative processes on family law reforms provide a template for building trust and consensus, ensuring that reforms reflect lived realities rather than abstract legal ideals.

- Codify Best Practices from Existing Personal Laws and State Models: India can adopt a “best-of-all-systems” approach, selectively codifying progressive provisions already present in various personal laws.

- For instance, equal succession rights under Hindu law, protections for women under the Special Marriage Act, and elements of Goa’s civil code can serve as reference points. Such selective codification reinforces the idea that the UCC is an evolution of existing laws, not their erasure.

- Ground Implementation in Constitutional Morality and Fundamental Rights: Any movement toward the UCC must be firmly anchored in constitutional morality, as emphasised in cases like Sabarimala (2018).

- This ensures that individual dignity, equality, and freedom take precedence over discriminatory customs. Importantly, reform must be insulated from political expediency and electoral considerations, reinforcing the judiciary’s consistent stance that the UCC is a constitutional goal best realised through principled legislation.

- Enable State-Level Experimentation Within a National Framework: Given India’s federal structure, States can act as laboratories of reform, piloting harmonised civil law provisions suited to their social context, while adhering to national constitutional standards.

- This bottom-up approach allows learning from successes and challenges before broader adoption, balancing uniformity with diversity.

Conclusion:

The Uniform Civil Code represents a constitutional aspiration to harmonise equality, dignity, and justice in India’s civil laws. If pursued through a phased, consultative, and rights-based approach, it can advance gender justice without eroding cultural diversity. Anchoring reform in constitutional morality rather than majoritarian impulses is essential to preserve social trust. A balanced UCC would strengthen rule of law and legal certainty, while respecting India’s pluralism. In doing so, it would also contribute to the achievement of SDG 5 (Gender Equality).

|

Drishti IAS – Mains Question Q. The Uniform Civil Code is envisaged as a constitutional instrument to promote equality and gender justice, yet its implementation raises concerns related to religious freedom and pluralism. |

FAQs

Q. What is the Uniform Civil Code (UCC)?

The Uniform Civil Code refers to a common set of civil laws governing marriage, divorce, inheritance, adoption, and succession for all citizens, irrespective of religion, as envisaged under Article 44 of the Constitution.

Q. Why is the UCC considered important in India?

The UCC is viewed as a means to ensure equality before law, gender justice, and legal uniformity, particularly by addressing discriminatory provisions present in certain personal laws.

Q. Why does the UCC remain a contentious issue?

It raises concerns related to freedom of religion (Article 25), cultural autonomy, minority rights, and India’s pluralistic social structure, making consensus difficult.

Q. Does the Constitution mandate immediate implementation of the UCC?

No. Article 44 is part of the Directive Principles of State Policy, which are non-justiciable and meant to guide the State toward gradual and consensual reform.

Q. What approach is considered suitable for implementing the UCC in India?

A phased, consultative, and rights-based approach, focusing on gender-neutral laws, stakeholder consultation, and constitutional morality rather than political expediency.

UPSC Civil Services Examination, Previous Year Questions (PYQs)

Prelims

Q. Consider the following provisions under the Directive Principles of State Policy as enshrined in the Constitution of India: (2012)

- Securing for citizens of India a uniform civil code

- Organising village Panchayats

- Promoting cottage industries in rural areas

- Securing for all the workers reasonable leisure and cultural opportunities

Which of the above are the Gandhian Principles that are reflected in the Directive Principles of State Policy?

(a) 1, 2 and 4 only

(b) 2 and 3 only

(c) 1, 3 and 4 only

(d) 1, 2, 3 and 4

Ans: (b)

Mains:

Q. Discuss the possible factors that inhibit India from enacting for its citizen a uniform civil code as provided for in the Directive Principles of State Policy. (2015)