Indian Polity

Strengthening Judicial Accountability in India

- 09 Jun 2025

- 22 min read

This editorial is based on “Impeachment motion against Allahabad High Court judge Yashwant Varma in Monsoon session” which was published in Times of India on 05/06/2025. The article brings into picture the impeachment against an Allahabad High Court judge, bringing renewed attention to the constitutional process for judicial accountability and the high threshold required to remove a sitting judge.

For Prelims: Indian Judiciary, Separation Of Powers, Supreme Court, High Courts, Judicial Review, Collegium System, Judicial overreach, Judges (Inquiry) Act, 1968, Supreme Court’s Recent intervention in setting specific timelines for the President to act on Bills (Reserved by Governer)

For Mains: Current Mechanism for Judicial Accountability in India, Key Factors Underscoring the Growing Imperative for Judicial Accountability in India.

The Union government's impeachment motion against Allahabad High Court Judge, following allegations of financial misconduct, brings judicial accountability into sharp focus. While India's Constitution provides mechanisms for judicial oversight, the rarity of such proceedings—raises questions about their practical implementation. The judiciary, as one of the three pillars of democratic governance, must be subject to the same rigorous standards of accountability as the executive and legislative branches. The current case thus offers an opportunity to examine how effectively India's existing judicial accountability systems function in practice.

What is the Current Mechanism for Judicial Accountability in India?

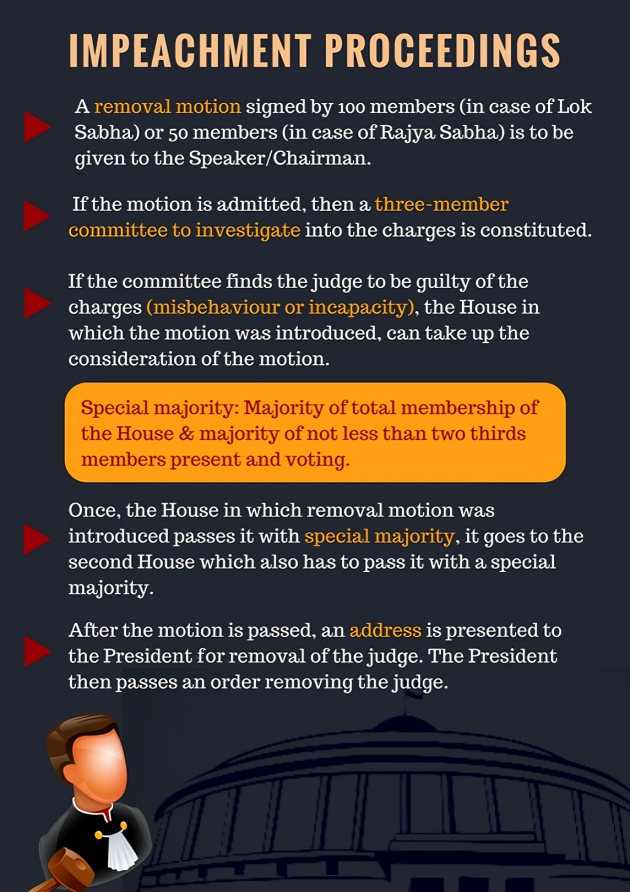

- Impeachment: The Constitution provides the "skeleton" for the removal of judges. It ensures that judges cannot be removed at the whim of the executive. Although the Constitution uses the term “impeachment” only for the President. For judges, the word is not mentioned, though it is often used informally to describe their removal process.

- Article 124(4): Outlines the removal of a Supreme Court Judge. It specifies that a judge can only be removed by an order of the President after an address by each House of Parliament.

- Articles 217 and 218 provide similar provisions for High Court judges,

- Grounds for Removal: The Constitution explicitly limits removal to only two grounds:

- Proven misbehaviour (e.g., corruption, lack of integrity, or moral turpitude).

- Incapacity (physical or mental inability to perform duties).

- The Judges (Inquiry) Act, 1968 is the statutory "instruction manual" that operationalizes the removal process mentioned in the Constitution.

- The Act sets out the following steps for removal from office: Under the Act, an impeachment motion may originate in either house of parliament.

- To initiate proceedings: (i) at least 100 members of Lok Sabha may give a signed notice to the speaker, or (ii) at least 50 members of Rajya Sabha may give a signed notice to the chairman.

- The speaker or chairman may consult individuals and examine relevant material related to the notice.

- Based on this, he or she may decide to either admit the motion or refuse to admit it.

- If admitted, a three-member inquiry committee—comprising a Supreme Court judge, a High Court Chief Justice, and a distinguished jurist, is constituted to investigate the charges.

- The judge concerned is given the charges and an opportunity to submit a written defence.

- The committee’s report is then placed before the concerned House; if it finds misbehaviour or incapacity, the removal motion is debated.

- For removal, the motion must be passed in each House by a majority of total membership and a two-thirds majority of members present and voting.

- Once approved by both Houses, it is sent to the President, who issues the removal order.

- No judge has been successfully impeached so far, as proceedings have either failed to secure the required majority or ended in resignation before completion.

- The Act sets out the following steps for removal from office: Under the Act, an impeachment motion may originate in either house of parliament.

- Article 124(4): Outlines the removal of a Supreme Court Judge. It specifies that a judge can only be removed by an order of the President after an address by each House of Parliament.

- In-House Mechanism: The in-house mechanism was created as a result of the Supreme Court’s judgement in C.Ravichandran Iyer v Justice A.M.Bhattacharjee (1995).

- The decision noted that it was a mechanism to fill in the “yawning gap” between proved misbehaviour and bad conduct inconsistent with the high office.

- Under the established “In-House Procedure” for the higher judiciary, the Chief Justice of India (CJI) is the competent authority to receive and examine complaints relating to the conduct of Supreme Court Judges and Chief Justices of High Courts.

- Likewise, the Chief Justices of the High Courts are empowered to receive complaints concerning the conduct of High Court Judges.

- If the complaint is found credible, a three-member committee is constituted to inquire into the complaint and may recommend removal or initiation of criminal proceedings.

- For complaints against a High Court judge, the committee comprises two Chief Justices of High Courts other than the concerned High Court and one High Court judge.

- For complaints against a Chief Justice of a High Court, the committee consists of one Supreme Court judge and two Chief Justices of other High Courts.

- For complaints against a Supreme Court judge, the committee is composed of three judges of the Supreme Court.

- Judicial Standards and Accountability Bill 2010 (Lapsed): This bill sought to introduce an external oversight body, the National Judicial Oversight Committee, along with other bodies for complaints and investigations.

- It was passed by the Lok Sabha but lapsed in the Rajya Sabha, leaving judicial accountability largely unaddressed through formal legislative channels.

- Judicial Review and Public Scrutiny: The judiciary is subject to judicial review by higher courts, but there is no independent external body or comprehensive statutory framework to oversee judicial conduct.

- Allegations against judges often lead to internal investigations or resignation, but such actions are not always transparent or publicly disclosed.

Instances of Impeachment Proceedings in Past

- Justice V. Ramaswami (Supreme Court, 1991): Financial irregularities and "extravagant spending" on his official residence while serving as Chief Justice of the Punjab and Haryana High Court.

- Outcome: The motion was defeated in the Lok Sabha because the ruling party abstained from voting, resulting in the motion failing to get the required 2/3rd majority.

- Justice Soumitra Sen (Calcutta High Court, 2011): Misappropriation of public funds while acting as a court-appointed receiver and misrepresenting facts to the court.

- Outcome: After the Rajya Sabha passed the impeachment motion, he resigned just before the motion was to be taken up in the Lok Sabha.

- Justice P.D. Dinakaran (Sikkim High Court, 2011): Massive land-grabbing, corruption, and abuse of judicial office.

- Outcome: He resigned from his post in July 2011 before the impeachment process against him could be completed in Parliament.

- Justice J.B. Pardiwala (Gujarat High Court, 2015): Making "objectionable remarks" regarding the reservation system in a judgment. 58 Rajya Sabha MPs signed the notice.

- Outcome: The motion was dropped when the judge formally withdrew/deleted the controversial remarks from his judgment shortly after the notice was moved.

- Justice Dipak Misra (Chief Justice of India, 2018): "Misuse of authority" in assigning cases (Master of Roster) and other administrative irregularities.

- This was the first-ever motion moved against a sitting Chief Justice of India.

- Outcome: The Chairman of the Rajya Sabha rejected the motion at the preliminary stage, stating the charges lacked "proved misbehavior."

- Justice Yashwant Varma (Delhi High Court, 2025): Financial misconduct following the discovery of bags of burnt currency at his residence. (The case is under development)

Related Supreme Court Judgements

- K. Veeraswami v. Union of India (1991): The Court held that judges of the High Courts and the Supreme Court are "public servants" and can be prosecuted for corruption.

- To protect judicial independence, the Supreme Court established that no FIR can be registered against a sitting High Court or Supreme Court judge without prior consultation and permission from the Chief Justice of India (CJI) to protect judicial independence from executive interference.

- CPIO, Supreme Court of India v. Subhash Chandra Agarwal (2019): The case was a landmark Supreme Court ruling that declared the office of the Chief Justice of India (CJI) a "public authority" under the Right to Information (RTI) Act, balancing transparency with judicial independence.

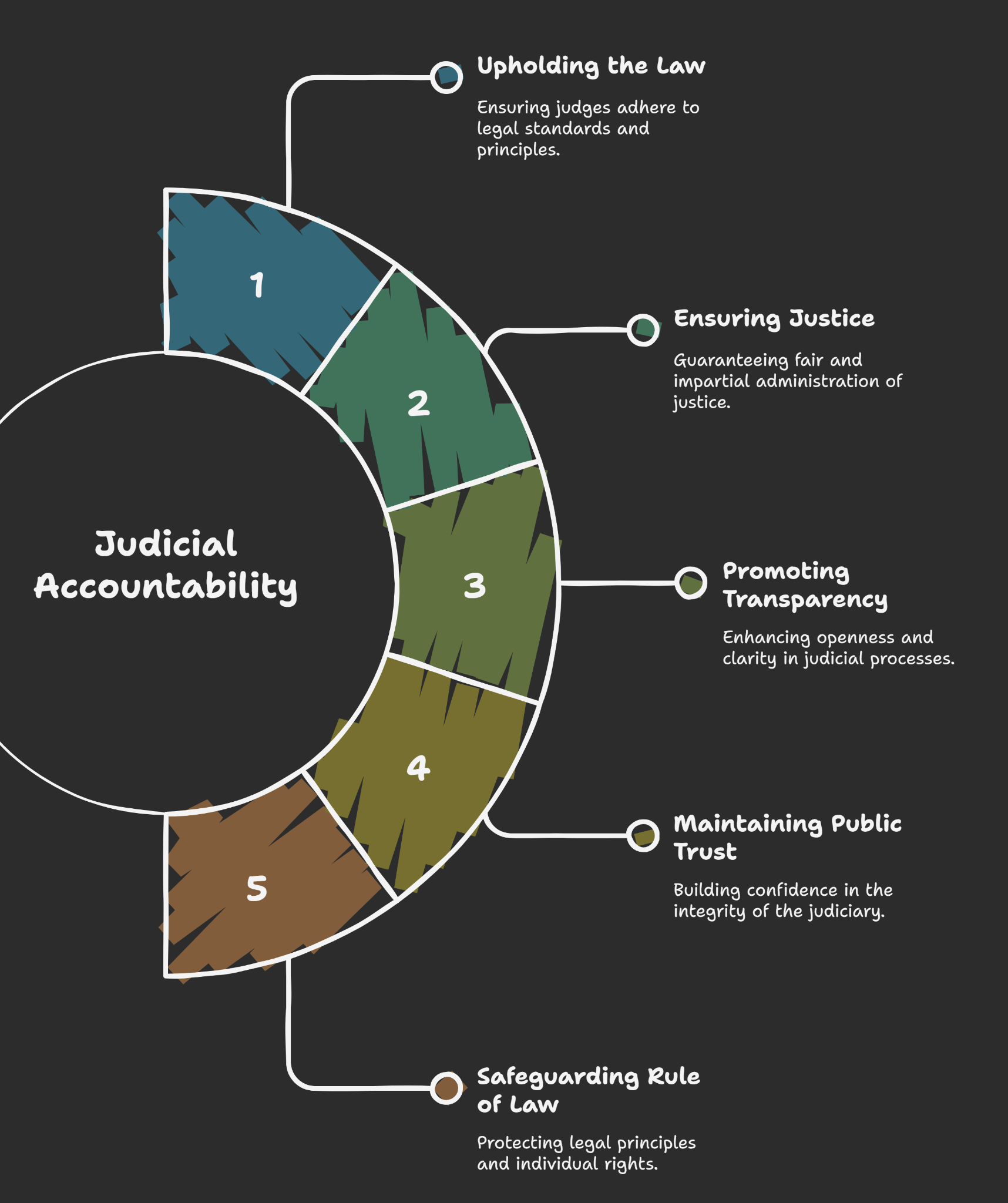

Why There is a Need for Greater Judicial Accountability?

- Lack of Robust Accountability Mechanisms in Judiciary: The existing frameworks for judicial accountability, such as the Judges (Inquiry) Act, 1968, are cumbersome and ineffective.

- Despite its importance, impeachment motions for judicial misconduct have not been successful, leading to public distrust in the judiciary’s ability to self-regulate.

- Judicial Independence vs. Judicial Accountability: The balance between maintaining judicial independence and ensuring accountability remains a core issue.

- Critics argue that too much autonomy leads to a lack of external scrutiny, fostering a culture of impunity.

- Judicial independence has become a shield against accountability, undermining public trust in the system.

- The issue over Justice Yashwant Varma of the Allahabad High Court, accused of corruption, and the Supreme Court’s in-house procedure for judicial discipline, reflects the lack of external checks despite serious charges.

- Critics argue that too much autonomy leads to a lack of external scrutiny, fostering a culture of impunity.

- Opacities in the Judicial Appointment Process: The lack of transparency in the judicial appointment process under the collegium system contributes to concerns over judicial accountability.

- Critics argue that this opacity not only breeds nepotism but also prevents scrutiny of judicial performance.

- Furthermore, the absence of prescribed norms regarding eligibility criteria and selection procedures further contributes to the perception of a closed-door affair.

- Inadequate External Oversight Mechanisms: The absence of a statutory, independent body to oversee judicial conduct exacerbates accountability issues.

- While the judiciary relies on internal mechanisms, they are often perceived as inadequate due to lack of transparency and public involvement.

- The judicial reforms bill of 2010, which proposed a National Judicial Oversight Committee, lapsed in 2014, leaving judicial oversight to self-regulation, which has often been opaque and ineffective.

- Challenges of Judicial Activism and Overreach: Judicial activism has led to the judiciary stepping into domains traditionally reserved for the executive and legislature.

- While this is seen as necessary in some cases, it raises concerns about the accountability of unelected judges making policy decisions.

- The Supreme Court’s recent intervention in setting specific timelines for the President to act on Bills reserved for their consideration by a Governor, have been criticized as an encroachment on executive functions, raising questions about judicial accountability.

- Global Shift Towards Judicial Transparency: Globally, there has been a growing trend towards judicial transparency and accountability, with many nations introducing external oversight mechanisms.

- Countries like the UK and the US have established independent judicial oversight bodies.

- India’s failure to implement such reforms contrasts with global standards, making the system more vulnerable to criticisms of opacity.

- Countries like the UK and the US have established independent judicial oversight bodies.

What are the Potential Risks Associated with Enforcing Judicial Accountability?

- Threat to Judicial Independence: Over-enforcement of judicial accountability can dilute judicial independence by exposing judges to executive or legislative pressure.

- Politicised mechanisms risk influencing judicial decision-making, as seen in concerns raised after the Lokpal order proposing jurisdiction over judges, later stayed by the Supreme Court to safeguard autonomy.

- Political Interference in the Judiciary: Accountability tools like impeachment are vulnerable to partisan manipulation, enabling political targeting of inconvenient judges.

- The failed impeachment of Justice V. Ramaswami (1993) highlighted how political calculations can override substantive misconduct allegations.

- Erosion of Public Confidence: Excessive scrutiny or punitive action may create a perception of judicial vulnerability, discouraging bold and independent judgments.

- Frequent use of contempt powers against critics further raises concerns about transparency and accountability, affecting public trust.

- Lack of Uniform Standards: The absence of a clear statutory framework for judicial accountability leads to inconsistent and opaque handling of misconduct cases.

- The ad-hoc in-house procedure, illustrated by controversies involving the Allahabad High Court, underscores risks of arbitrariness and selective enforcement.

What Measures can be Adopted to Ensure Robust and Transparent Judicial Accountability Framework in India?

- Establishment of an Independent Judicial Oversight Body: Create a National Judicial Oversight Committee comprising retired judges, legal experts, and eminent persons to impartially investigate complaints of judicial misconduct without political interference.

- Drawing from the UK’s Judicial Conduct Investigations Office, it can frame a binding National Judicial Code of Conduct to clearly define ethical standards and conflicts of interest.

- Revamping the Impeachment Process: Reform impeachment to ensure transparency, fixed timelines, and public disclosure of proceedings.

- Amend the Judges (Inquiry) Act, 1968 to mandate completion of inquiries even after resignation or retirement, preventing evasion of accountability, as seen in cases like Justices Soumitra Sen and P.D. Dinakaran.

- Public Disclosure of Judicial Assets and Liabilities: Mandate annual public disclosure of judges’ assets and liabilities, subject to independent scrutiny, to deter corruption and enhance transparency.

- This would strengthen the 1997 Supreme Court resolution on asset declaration by moving from internal disclosure to public accountability.

- Strengthening the In-House Mechanism with Transparency: Reform the in-house procedure by formalising processes and publishing inquiry outcomes in a calibrated manner.

- Clear communication of disciplinary action would enhance credibility while preserving judicial independence.

- Also, India needs to revive a reformed National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC) with balanced representation and safeguards for judicial independence to enhance transparency and institutional accountability.

- Judicial Performance Review and Reporting: Introduce periodic performance and ethics reviews focusing on quality of judgments and professional conduct, with aggregate findings disclosed publicly.

- The National Judicial Data Grid (NJDG) can be leveraged to track efficiency, quality of disposal, and systemic bottlenecks.

- Whistleblower Protection for Judicial Misconduct: Institutionalise strong whistleblower safeguards within the judiciary to protect court staff and stakeholders reporting misconduct. This would promote internal accountability and a culture of self-correction.

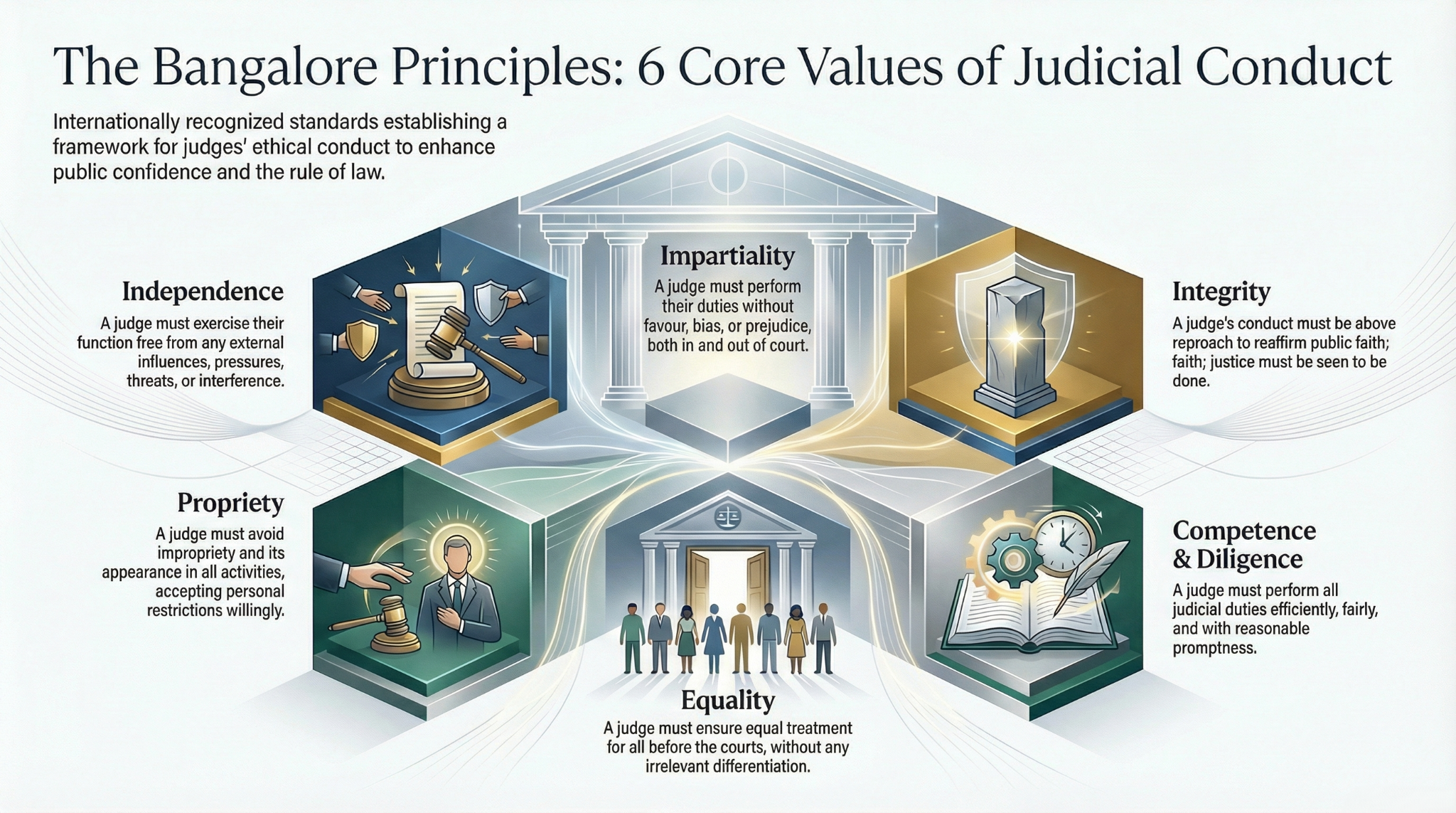

- Institutionalising Ethical Standards: Ensure adherence to the Bangalore Principles of Judicial Conduct and the Restatement of Values of Judicial Life through mandatory ethics training, periodic reaffirmation, and integration into disciplinary mechanisms, ensuring consistent and enforceable ethical governance.

Conclusion:

Current judicial accountability mechanisms, such as the Judges (Inquiry) Act, are often inefficient and politically influenced. To strengthen accountability, reforms like an independent oversight body, transparent asset declarations, and regular reviews are needed. These steps will safeguard judicial independence while boosting public trust. As former CJI D.Y. Chandrachud highlighted, "True judicial independence is not a shield to protect wrongdoing, but an instrument to secure the fulfilment of constitutional values."

|

Drishti Mains Question: Judicial accountability is a cornerstone of democratic governance, but it must be balanced with judicial independence. Examine the current mechanisms for judicial accountability in India. What reforms are needed to ensure a more transparent, effective, and accountable judiciary? |

UPSC Civil Services Examination Previous Year Question (PYQ)

Prelims:

Q. With reference to the Indian judiciary, consider the following statements:

- Any retired judge of the Supreme Court of India can be called back to sit and act as a Supreme Court judge by the Chief Justice of India with the prior permission of the President of India.

- A High Court in India has the power to review its own judgement as the Supreme Court does.

Which of the statements given above is/are correct? (2021)

(a) 1 only

(b) 2 only

(c) Both 1 and 2

(d) Neither I nor 2

Ans: (c)

Mains:

Q. Discuss the desirability of greater representation to women in the higher judiciary to ensure diversity, equity and inclusiveness. (2021)

Q. Critically examine the Supreme Court’s judgement on ‘National Judicial Appointments Commission Act, 2014’ with reference to appointment of judges of higher judiciary in India. (2017)