Indian Polity

Private Member’s Bill on Judicial Diversity

- 21 Feb 2026

- 13 min read

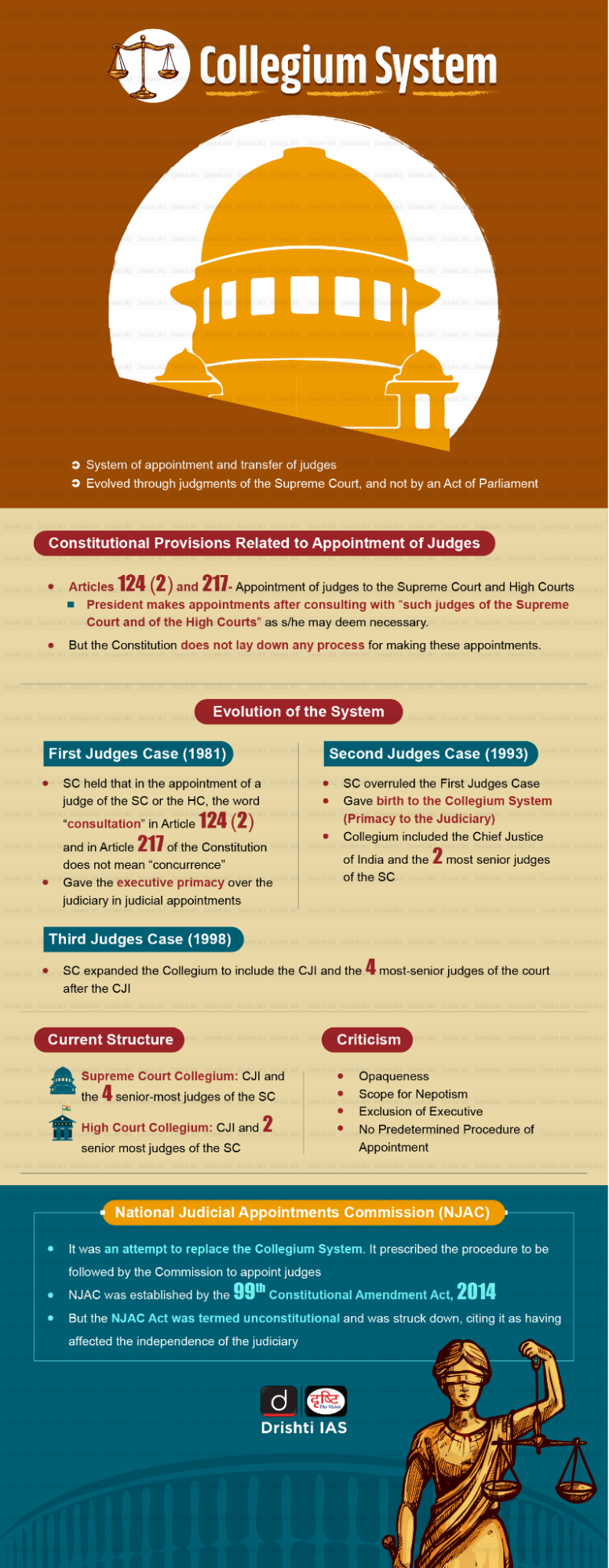

For Prelims: Private Member's Bill, Supreme Court of India, Judicial Appointments, Chief Justice of India, Collegium System

For Mains: Judicial appointments and Collegium system reforms, Diversity and representation in higher judiciary, Access to justice and regional benches of the Supreme Court

Why in News?

A Private Member's Bill has been introduced in Parliament seeking to amend the Constitution to mandate social diversity in higher judicial appointments and establish regional benches of the Supreme Court (SC) of India, aiming to make the highest court more accessible to citizens across the country.

Summary

- Private Member’s Bill proposes proportional representation for SCs, STs, OBCs, women, and minorities in higher judicial appointments, and regional Supreme Court benches to improve access to justice.

- The higher judiciary faces structural barriers such as opaque collegium processes, nepotism, absence of constitutional diversity mandates, gendered career constraints, and geographical centralisation in Delhi, which limit representation of marginalised groups.

What does the New Private Member Bill Propose for Judicial Diversity?

- Current Deficit: Proportional Representation: The Bill mandates that due representation must be given to Scheduled Castes (SC), Scheduled Tribes (ST), Other Backward Classes (OBC), religious minorities, and women in proportion to their population when appointing judges to both the Supreme Court and High Courts.

- Data shows that between 2018 and 2024, only about 20% of appointees to the higher judiciary belonged to the SC, ST, and OBC.

- Furthermore, women and religious minorities represent less than 15% and 5%, respectively.

- Data shows that between 2018 and 2024, only about 20% of appointees to the higher judiciary belonged to the SC, ST, and OBC.

- Time-Bound Appointments: It proposes a strict maximum timeline of 90 days for the Central government to formally notify the recommendations made by the collegium to avoid arbitrary delays.

- Regional Benches of the Supreme Court: The Bill proposes permanent regional appellate benches of the Supreme Court in New Delhi, Kolkata, Mumbai, and Chennai to handle regular appeals.

- Matters of national constitutional importance would remain exclusively with the Constitution Bench in Delhi.

- The Supreme Court currently sits exclusively in New Delhi, it severely restricts access to justice for common citizens and litigants living in distant southern, eastern, and north-eastern states.

Constitutional Provisions Regarding Supreme Court's Seat and Judicial Appointments

- Article 130: Declares that the seat of the Supreme Court shall be in Delhi, or at such other places as the Chief Justice of India (CJI) may decide with the prior approval of the President.

- Article 124: SC judges appointed by the President in consultation with the CJI and other judges.

- Article 217: High Court (HC) judges appointed by the President in consultation with CJI, Governor, and HC Chief Justice.

- Ad hoc Judges (Article 127): If quorum of SC judges is not available, CJI (with President’s consent) can request a HC judge to sit in SC.

- Acting CJI (Article 126): In case of vacancy/absence, senior most available SC judge appointed by the President.

- Retired Judges (Article 128): With President’s consent, CJI may request a retired SC judge to sit and act as SC judge for a specified period.

- Article 224A: A retired High Court judge may be requested to sit and act as an ad hoc judge of a High Court, with the prior consent of the President, on a reference made by the Chief Justice of the High Court.

- Appointment Procedures:

- CJI: Outgoing CJI recommends a successor, usually by seniority.

- SC Judges: CJI initiates the recommendation, consulting Collegium members and the senior-most judge from the candidate’s High Court. Their opinions are recorded in writing.

- The Collegium’s recommendation is sent to the Law Minister, then the Prime Minister, who advises the President for the appointment.

- HC Chief Justices/Judges: The Chief Justice of a High Court is appointed by the President in consultation with the CJI and the Governor of the State.

- The procedure for appointing puisne Judges is the same except that the Chief Justice of the High Court concerned is also consulted.

What are the Challenges Hindering Diversity in Judicial Appointments?

- Lack of Transparency: The Collegium, which holds the power to recommend judges for the higher judiciary, operates behind closed doors.

- Because there are no publicly defined criteria, binding diversity metrics, or published minutes for these selections, the process is highly susceptible to unconscious biases.

- The "Uncle Judge" Syndrome: Nepotism and familial influence are persistent criticisms. A significant percentage of judges in the higher judiciary are related to former judges or elite legal families.

- This creates an invisible, exclusionary barrier for first-generation lawyers, particularly those from marginalized backgrounds.

- No Constitutional Mandate: Unlike the legislature or public employment, the Indian Constitution does not mandate reservations for SC, ST, OBC, or women in the higher judiciary (under Articles 124 and 217).

- Without formal quotas, diversity relies entirely on the discretion of the Collegium, making SCs, STs, and minorities remain severely underrepresented.

- The "Leaky Pipeline": While women enter law schools and the lower judiciary in large numbers (often aided by state-level reservations), their presence drops drastically at the High Court and Supreme Court levels.

- As of late 2024, women constituted only about 14% of High Court judges. Only two of the 25 High Courts have women Chief Justices.

- Workplace Realities: The demanding nature of litigation, combined with disproportionate caregiving responsibilities and a lack of institutional support (such as childcare facilities or even basic infrastructure in some lower courts), forces many women to step away from the traditional, uninterrupted career paths required for elevation to the bench.

- "Old Boys' Club" Mentality: Elevation from the bar to the bench relies heavily on professional visibility, senior designations, and recommendations within elite legal circles.

- These circles are traditionally male-dominated and patriarchal. Lawyers outside these established networks struggle to gain the necessary recognition to be considered for judgeship.

- Geographical and Economic Centralization: Supreme Court practice is highly centralized in New Delhi.

- The immense financial and logistical cost of relocating and establishing a practice in the capital prevents highly talented lawyers from distant regions (such as the Northeast or deep South) from building the visibility required for elevation to the Supreme Court.

- Lack of Diversity Metrics and Audits: The current Memorandum of Procedure (MoP) for appointing judges does not require disclosure of candidates’ demographic data. Without regular audits, monitoring progress or ensuring accountability for inclusivity remains difficult.

What Measures can Strengthen Diversity in Judicial Appointments?

- Implementing Regional Benches via Article 130: As previously recommended by the 229th Law Commission of India Report (2009) and Parliamentary Standing Committees (2021-22), the Supreme Court does not necessarily need a constitutional amendment to set up regional benches.

- The CJI can establish them under the existing provisions of Article 130 in a phased, time-bound manner.

- Workplace Infrastructure: Improving basic infrastructure in lower and high courts (like crèches, safe washrooms, and strict anti-harassment committees) is crucial to preventing women from dropping out of the litigation sector before they reach the seniority required for judgeship.

- Formal Mentorship: Establishing institutional mentoring programs for first-generation, Dalit, Adivasi, and minority lawyers to help them build their practice, gain visibility, and prepare for judicial roles.

- NJAC: Experts advocate for reviving a modified version of the National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC).

- By including representatives from the judiciary, the executive, Bar Councils, and civil society/academia, the selection process becomes democratized, reducing nepotism and broadening the search for talent.

- Formal Metrics: The current MoP (the rulebook for appointing judges) focuses on merit and seniority but lacks binding diversity mandates.

- Amending the MoP to explicitly include demographic diversity (caste, gender, religion, and region) as a core criterion would force the Collegium to actively seek out diverse candidates.

Conclusion

Ensuring diversity in India's higher judiciary is essential to building a legal system that truly reflects the lived realities of all its citizens. Implementing structural reforms, such as transparent selection criteria and regional benches, will help dismantle historical barriers and elitism within the courts. Ultimately, a more representative bench strengthens the rule of law, enriches constitutional jurisprudence, and deepens public trust in the justice system.

|

Drishti Mains Question: Q. “Diversity in the judiciary is essential for substantive justice.” Examine in the context of India’s higher judicial appointments. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What does Article 130 of the Constitution provide?

It declares Delhi as the seat of the Supreme Court but allows the CJI, with Presidential approval, to hold sittings elsewhere.

2. What is the key objective of the proposed Private Member’s Bill?

To mandate social diversity in higher judiciary appointments and establish regional Supreme Court benches for better access to justice.

3. Why is diversity in the judiciary considered important?

It improves representation, enriches constitutional interpretation, and strengthens public trust in the justice system.

4. What is the main criticism of the Collegium system?

Lack of transparency, absence of diversity metrics, and susceptibility to nepotism (“Uncle Judge” syndrome).

5. How can regional benches reduce judicial pendency?

By decentralising appellate workload, improving accessibility, and enabling faster disposal of cases.

UPSC Civil Services Examination, Previous Year Questions (PYQs)

Prelims

Q. With reference to the Indian judiciary, consider the following statements: (2021)

- Any retired judge of the Supreme Court of India can be called back to sit and act as a Supreme Court judge by the Chief Justice of India with the prior permission of the President of India.

- A High Court in India has the power to review its own judgement as the Supreme Court does.

Which of the statements given above is/are correct?

(a) 1 only

(b) 2 only

(c) Both 1 and 2

(d) Neither 1 nor 2

Ans: A

Mains

Q. Critically examine the Supreme Court’s judgement on ‘National Judicial Appointments Commission Act, 2014’ with reference to the appointment of judges of higher judiciary in India. (2017)