Social Issues

Menstrual Health as a Fundamental Right

- 04 Feb 2026

- 17 min read

For Prelims: Supreme Court of India, Menstruation, Article 21, Janaushadhi Kendras

For Mains: Expanding scope of Article 21: dignity, health, and bodily autonomy, Substantive equality under Article 14 and gender-responsive governance, Menstrual health as a public health, education, and human rights issue

Why in News?

The Supreme Court of India (SC) , in the case of Dr. Jaya Thakur v. Government of India & Ors. (2026), officially recognized Menstrual Health and Hygiene (MHH) as a fundamental right under Article 21 (Right to Life and Dignity).

- The court issued a continuing mandamus (a judicial order through which it keeps a matter pending to monitor compliance ) directing the Centre and states to ensure free sanitary napkins and functional toilets in all schools.

Summary

- The Supreme Court has declared Menstrual Health and Hygiene (MHH) an integral part of the right to life, dignity, bodily autonomy, equality, and education under Articles 21 and 14, transforming it from a welfare concern into a binding constitutional entitlement.

- The judgment mandates free sanitary products, functional gender-segregated toilets, safe waste disposal, sensitisation of students and teachers, and strict accountability, while exposing major implementation challenges in infrastructure, funding, and social attitudes.

What did the Supreme Court Rule on Menstrual Health?

- Article 21 (Dignity and Bodily Autonomy): The Court ruled that the inability to access MHH facilities subjects girls to "stigma, stereotyping, and humiliation", which directly violates their right to live with dignity.

- Forced absenteeism or dropouts due to biological realities are seen as violations of bodily autonomy.

- The SC held that MHH are inherent to a life lived with dignity, not mere survival. The right covers bodily autonomy, privacy, and reproductive health of menstruating girls.

- Substantive Equality (Article 14): The judgment moves beyond "formal equality" (treating everyone the same). It argues that ignoring the unique biological needs of women creates a "structural exclusion".

- SC noted that true equality requires the State to address these specific disadvantages to put girls on an equal footing with their male peers.

- Right to Education (RTE): Under RTE Act 2009, the Court ruled that "free" does not just mean waiving tuition fees. It requires removing any financial barrier (including the cost of sanitary products) that prevents a child from completing their education.

- Under RTE Act 2009, the requirement for separate toilets is no longer just an "infrastructural" guideline but a "substantive" one. Failure to provide these facilities is now termed a "stark constitutional failure."

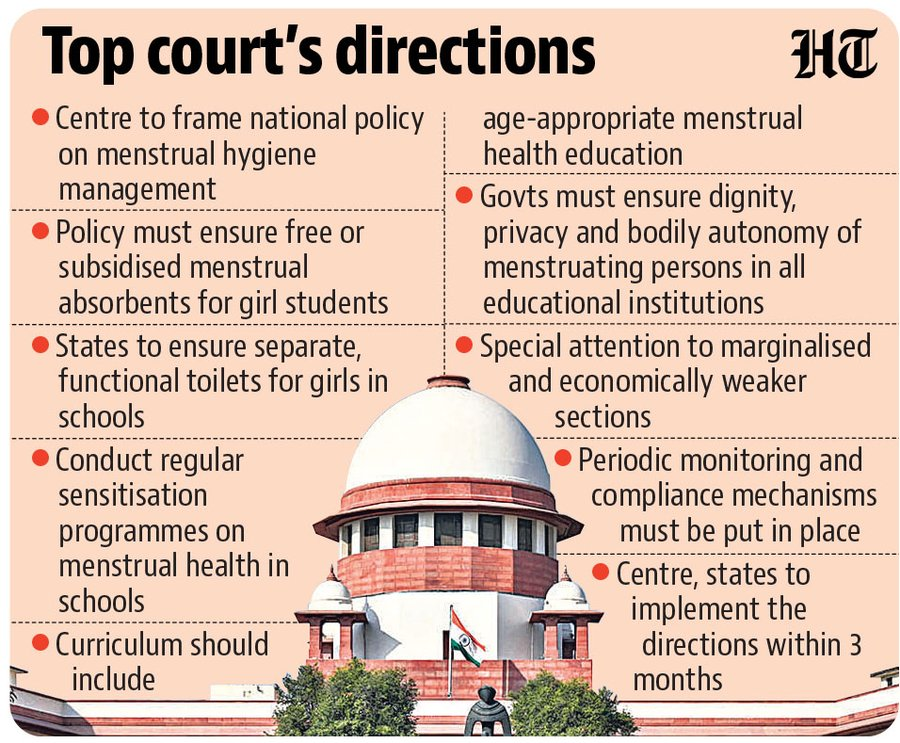

Directions Issued by SC

- Accountability & Feedback: District Education Officers (DEO) must conduct periodic inspections and, crucially, obtain "anonymous feedback" via surveys from the students themselves to assess the ground reality.

- SC also asked the National Commission for Protection of Child Rights (NCPCR), or, State CPCR to oversee implementation of its orders stating that its directions and the Union’s Menstrual Hygiene Policy for School-going Girls (Classes 6th–12th) shall operate as mandatory pan-India standards, in addition to existing state policies and schemes.

- Provision of Products: Every school (government and private) must provide free oxo-biodegradable sanitary napkins via vending machines.

- Menstrual Hygiene Management (MHM) Corners: Schools must establish dedicated corners stocked with essentials like spare innerwear, uniforms, and disposable bags to handle "menstruation-related exigencies."

- Sanitation Infrastructure: Functional, gender-segregated toilets with water connectivity and soap must be available at all times.

- Waste Management: Safe and environmentally compliant disposal mechanisms must be integrated as per Solid Waste Management (SWM) Rules, 2026.

- Male Sensitization: The Court mandated that the NCERT and SCERTs incorporate gender-responsive curricula. It noted that boys must be educated about the biological reality of menstruation to prevent harassment.

- All teachers, regardless of gender, are to be trained to support menstruating students.

Did you Know?

- Menstruation is a normal and natural biological process in which the uterine lining sheds and is discharged as blood and tissue through the vagina pregnancy does not occur in women and girls of reproductive age.

- Menstruation is regulated by hormonal changes and usually occurs once a month from puberty (menarche) to menopause, with most women menstruating for a few days each month over nearly seven years in total during their lifetime.

- Menstruation is a key indicator of reproductive health and is not an illness or impurity, but a healthy physiological function of the female body.

- Poor menstrual hygiene can lead to reproductive and urinary tract infections, especially where clean water and sanitation are unavailable.

- Polycystic Ovarian Disease (PCOD) is a hormonal disorder that can disrupt menstruation, causing irregular, delayed, or absent periods.

- Even with PCOD, menstruation remains a normal physiological process, not a disease or impurity.

What is the Significance of MHH as a Fundamental Right?

- Establishment of "Biological Citizenship": The ruling creates a new category of rights where the State is held responsible for the "biological tax" women pay.

- If a woman is disadvantaged by a natural process (menstruation), the State must intervene to neutralize that disadvantage.

- This moves from Negative Liberty (the State won't stop you from going to school) to Positive Liberty (the State must provide the pads and toilets so you can go to school).

- Redefining the "Free" in RTE: NFHS-5 reveals that only 77.3% of women aged 15–24 use hygienic menstrual methods, while nearly one-fourth remain deprived of basic menstrual support.

- This deprivation directly translates into educational exclusion, with around 23% of girls experiencing dropout or chronic absenteeism after puberty.

- Recognising this linkage, the Supreme Court identified the lack of access to sanitary products, water, toilets, and safe disposal as “menstrual poverty” that undermines bodily autonomy and denies girls equal enjoyment of the RTE.

- By mandating free sanitary pads, the Court redefines “free education” as a condition that is materially enabling, not merely nominal, thereby making the RTE substantively enforceable.

- Socio-Legal Engineering: By mandating sensitization and training, the Court is using law as a tool for social change. It recognizes that the "hostile environment" created by un-sensitized boys and male teachers is a primary cause of dropouts.

Government Measures to Improve Menstrual Hygiene

- Scheme for Promotion of Menstrual Hygiene: Targets adolescent girls aged ten to nineteen years. It emphasises awareness, access to sanitary napkins, and environmentally safe disposal.

- Menstrual Hygiene Policy for School-Going Girls: Ensures low-cost products, gender-segregated toilets, and disposal facilities. Integrates menstrual hygiene education into school curriculum.

- PMBJP (Pradhan Mantri Bharatiya Janaushadhi Pariyojna): Over 16,000 Janaushadhi Kendras provide Oxo-biodegradable 'Suvidha' napkins at just Rs. 1 per pad.

- Cumulative sales crossed 96 crore pads by November 2025.

- ASHA Network: Frontline workers distribute subsidized packs (Rs. 6 for 6 napkins) and conduct monthly community meetings to break societal taboos.

- Women & Child Development Initiatives: Menstrual health awareness is a key component of Mission Shakti (Beti Bachao Beti Padhao), Rashtriya Kishor Swasthya Karyakram (RKSK), and Scheme for Adolescent Girls (SAG).

- Infrastructure & Education:

- Samagra Shiksha (Ministry of Education): Provides funds for the installation of sanitary pad vending machines and incinerators in schools.

- Swachh Bharat Mission: Provides National Guidelines on MHM for rural areas, focusing on behavior change and sanitation.

- UGC Advisory: Mandates Higher Educational Institutions (HEIs) to ensure sanitary facilities at conspicuous locations.

What are the Key Challenges in Implementing the MHH Guidelines?

- Last-mile infrastructure deficit: Toilets exist on paper, but lack of running water, soap, disposal facilities, and ensuring regular stocking of Vending machine maintenance in rural and remote schools remains uncertain.

- Absence of dedicated cleaning staff and recurring O&M budgets leads to rapid deterioration of facilities.

- Procurement and Supply Constraints: Scaling up affordable, quality oxo-biodegradable sanitary pads within tight timelines poses serious logistical challenges for states.

- Without earmarked funding, MHM expenditure may strain state education budgets and crowd out schemes like midday meals or teacher recruitment.

- Unsafe Waste Disposal Risks: Inadequate technical capacity for operating incinerators and absence of standardised menstrual waste protocols threaten environmental compliance.

- Feedback Authenticity Concerns: Power hierarchies and fear among students may prevent honest reporting through surveys and grievance mechanisms.

- Despite WHO guidelines and the Ministry of Education’s 2021 directive on sensitisation, schools often continue to reinforce gender hierarchies, with menstruation treated as dirty, leading to embarrassment, stigma, and exclusion of girls.

What Measures Can Strengthen MHH?

- Inclusivity: The policy must be inclusive of trans-men and non-binary individuals who also menstruate.

- Sashaktikaran (Empowerment): State governments should leverage Self-Help Groups (SHGs) for the local production of biodegradable napkins.

- Assured Water Supply: Integrating school toilets with the Jal Jeevan Mission to ensure 24/7 running water, which is non-negotiable for menstrual hygiene.

- Privacy-First Design: Installing "privacy screens" and internal latches in toilets, along with mirrors and hooks, to allow girls to change products and wash without fear of exposure.

- Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT) Alternative: In areas where the supply chain is broken, the government could explore "Pad Credits" or DBT to the girl’s (or mother’s) account specifically for the purchase of hygienic products.

- Disposal as a Service: Engaging local "Safai Mitras" (sanitation workers) through the Swachh Bharat Mission (Grameen) to collect and process menstrual waste, ensuring it doesn't end up in general landfills.

- Standardized Procurement: States should establish a Centralized Procurement Cell to ensure that all napkins distributed meet the ASTM D-6954 or IS 17518 standards (focused on evaluating the degradation of plastics in the environment) for biodegradability, preventing the distribution of low-quality, plastic-heavy alternatives.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court’s ruling gives constitutional force to a simple but powerful truth “A period should end a sentence, not a girl’s education.” By recognising menstrual health as central to dignity, equality, and education, the judgment opens the door for structural reform, sustained state responsibility, and real gender justice.

|

Drishti Mains Question: “The recognition of menstrual health as a fundamental right marks a shift from welfare to entitlement.” Examine this statement in light of Article 21 |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What did the Supreme Court rule on menstrual health in 2026?

It held menstrual health and hygiene to be an integral part of the right to life, dignity, bodily autonomy, and reproductive health under Article 21.

2. How does the judgment link menstrual health with the Right to Education?

The Court ruled that period poverty is a financial barrier under the RTE Act and that lack of pads or toilets amounts to a constitutional failure.

3. What key directions were issued to schools?

Schools must provide free oxo-biodegradable sanitary pads, functional gender-segregated toilets, MHM corners, safe waste disposal, and trained staff.

4. Why is the concept of “substantive equality” important in this ruling?

It recognises that treating everyone the same ignores biological disadvantages and that the State must actively correct such structural exclusions.

5. What are the main implementation challenges of the MHH guidelines?

Last-mile infrastructure gaps, water scarcity, procurement of quality pads, waste disposal capacity, and ensuring genuine student feedback.

UPSC Civil Services Examination, Previous Year Questions (PYQs)

Mains

Q. What are the continued challenges for women in India against time and space?(2019)