Social Justice

Shaping India's Nutrition Revolution

This editorial is based on “To improve both crop and human nutrition, India needs a paradigm shift” which was published in The Indian Express on 07/05/2024. The article brings into picture the paradox of India’s food security—while the nation has become the world’s largest rice exporter and runs the largest food distribution programme, deteriorating soil health and nutrient imbalance threaten both crop productivity and human nutrition.

For Prelims: Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Anna Yojana, POSHAN Abhiyaan, International Year of Millets 2023, “Shree Anna” campaign, Hidden hunger, Soil Health Card Scheme, Ayushman Arogya Mandirs, Minimum Support Price, Farmer Producer Organisations .

For Mains: Key Strides of India in Ensuring Nutritional Security, Key Issues Hindering Nutritional Security in India.

India has made a historic leap from food scarcity in the 1960s to becoming the world’s largest rice exporter and running the largest public food distribution programme. Yet, this achievement masks a deeper crisis—widespread malnutrition persists. The core of this paradox lies in India's neglected soil health, marked by severe nutrient deficiencies and imbalanced fertilizer use. Poor-quality soils yield calorie-rich but nutrient-poor crops, silently fueling hidden hunger. Ensuring nutritional security now demands a shift from quantity-focused agriculture to quality-centered food systems.

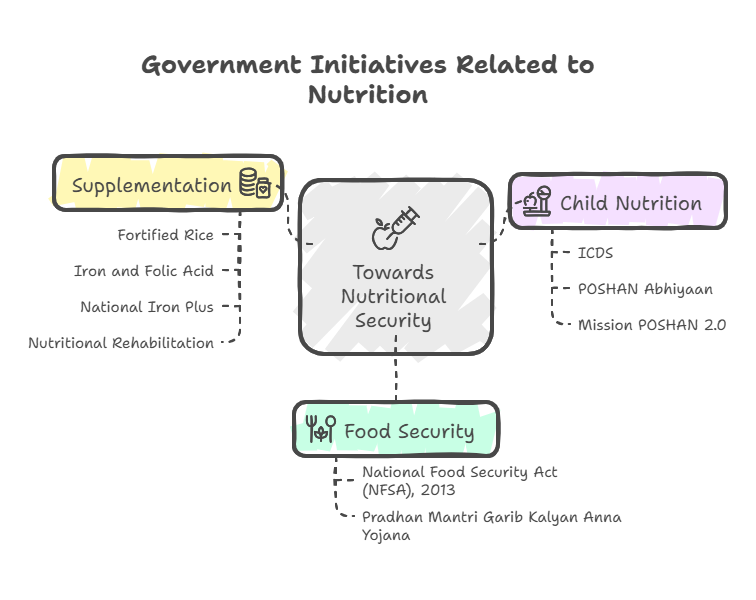

What are the Key Strides of India in Ensuring Nutritional Security?

- Expansion of Universal Food Access through PMGKAY and NFSA: India has institutionalised food security through legally backed entitlements and free food provisioning for the poor.

- By extending Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Anna Yojana (PM-GKAY) for five more years from 2024 and reinforcing NFSA coverage, food availability for over 800 million people is ensured.

- This guarantees caloric security and protects vulnerable populations from inflationary shocks.

- PMGKAY now covers 81.35 crore beneficiaries with 5 kg rice/wheat/month.

- As of July 2024, the Central Pool holds 608.75 lakh metric tonnes of foodgrains, significantly surpassing the stocking norm of 411.20 lakh metric tonnes.

- Targeted Maternal and Child Nutrition through ICDS and POSHAN Abhiyaan: Through ICDS and POSHAN Abhiyaan, India has built the world’s largest community-based nutrition delivery system.

- Anganwadi Centres now serve as hubs for early childhood nutrition, maternal care, and growth monitoring. The convergence model improves service outreach and impact.

- 100+ crore awareness activities under POSHAN Abhiyaan were observed during Poshan Maah in 2024.

- POSHAN Tracker digitised 13.9 lakh Anganwadi centres for real-time service delivery.

- Policy Push for Millets and Crop Diversification: With the International Year of Millets 2023, India has repositioned millets as “nutri-cereals” to enhance dietary diversity and climate resilience.

- The inclusion of millets in government procurement and schemes expands access to protein, fibre-, and mineral-rich food. This supports both health and farmer income.

- Millets included NFSA, ICDS, and school feeding programmes in select states. Budget 2023 announced the “Shree Anna” campaign and millet-focused research support.

- Price Stabilisation for Affordable Nutrition: To ensure affordability of nutritious staples, India has actively used price management tools and launched subsidised retail schemes.

- This shields the poor from food inflation and supports dietary adequacy. Public procurement and buffer stock mechanisms have been leveraged smartly.

- Bharat Dal, Bharat Atta, Bharat Rice retail at subsidised rates via NAFED, NCCF outlets.

- Global Leadership in Food System Transformation: India has emerged as a global player in food security, contributing to nutrition goals beyond its borders.

- As a food surplus country, its policy and implementation experience is shaping South-South cooperation in nutrition. This marks a reversal from past dependency.

- India is the largest rice exporter (20.2 MT in FY25) and second-largest food grain producer.

- From PL-480 dependency (US Public Law 480 (PL-480) program for food aid, primarily wheat) in the 1960s to current self-sufficiency and export leadership.

What are the Key Issues Hindering Nutritional Security in India?

- Persistent Child Malnutrition Despite Food Surplus: India has transitioned from food scarcity to surplus, yet child malnutrition remains alarmingly high due to a focus on calorie distribution over nutritional quality.

- NFHS-5 shows 35.5% children under 5 are stunted, 19.3% wasted and 32.1% underweight.

- India had by far the largest number of zero-food children (6.7 million), which is almost half of all zero-food children in the 92 countries.

- Micronutrient Deficiencies Linked to Soil Health Crisis: Soil degradation and nutrient imbalance directly affect the nutritional value of food, reducing key micronutrients like zinc and iron in crops.

- This leads to “hidden hunger” where food is available but lacks essential nutrients. Current fertiliser use patterns exacerbate the issue.

- Of more than 8.8 million samples tested under the Soil Health Card Scheme in 2024, less than 5% of Indian soils have high or sufficient nitrogen.

- Zinc-deficient soils correlate with stunting in children-a public health link now recognised.

- Over-Reliance on Cereal-Centric Food Policies: India’s food security strategy is cereal-heavy, focused on rice and wheat, neglecting pulses, vegetables, and millets critical for nutrition.

- This leads to dietary monotony and insufficient intake of proteins, vitamins, and minerals. Even flagship schemes reinforce this cereal bias.

- PMGKAY covers 81.35 crore people with 5 kg rice/wheat per month — but lacks diet diversity.

- Though 406 LMT of fortified rice has been distributed since 2019 — a step forward, protein intake gaps persist.

- Gendered Dimensions of Malnutrition: Nutritional inequality is deeply rooted in gender norms, with women and girls often eating last and least.

- Anaemia, poor maternal nutrition, and inadequate prenatal care perpetuate intergenerational malnutrition. Empowerment is key but under-addressed in food policies.

- Recent government data state that around 57% of women (15–49) are anaemic. NFHS-5 recorded 24% adult women to be overweight or obese c

- Children born to undernourished women are more likely to be low birthweight and stunted.

- Urban-Rural and Socioeconomic Inequities in Nutrition Access: Rural, tribal, and low-income households suffer disproportionately from malnutrition due to poor access to health and nutrition services.

- Urban areas now face rising obesity and NCDs — indicating a “double burden” of malnutrition. Public health efforts are unevenly distributed

- Stunting is higher among children in rural areas (37%) than urban areas (30%) (NFHS-5).

- Inadequate Reach and Quality of Health & Nutrition Infrastructure: Despite schemes like ICDS and Poshan Abhiyaan, delivery remains patchy due to infrastructure gaps, staffing issues, and poor convergence.

- Ayushman Arogya Mandirs are underutilised for nutrition services. Monitoring and targeting remain weak.

- Only 66% of POSHAN Abhiyaan funds spent as of 2022; HWC coverage uneven across regions. (ORF India)

- Sanitation, Hygiene and Environmental Health Linkages: Poor WASH (Water, Sanitation, Hygiene) practices increase disease burden, reducing nutrient absorption and exacerbating undernutrition.

- Environmental factors like contaminated water, open defecation, and pollution remain serious barriers to nutrition.

- 50% of malnutrition is linked to repeated diarrhoea from poor hygiene (WHO).

- India still has ~620 million people practicing open defecation in some areas (UNICEF, 2021).

- Price Volatility and Affordability of Nutritious Food: Inflation, supply shocks, and unequal income growth have made nutritious food unaffordable for many.

- FAO Report (2023) states that 74.1% of Indians are unable to afford a healthy diet. Even with food grain security, access to fruits, pulses, and animal proteins is limited for poor households. Recent food price spikes worsen the crisis.

What Measures can India Adopt to Enhance Nutritional Security in India?

- Shift from Calorie Security to Nutrient-Dense Food Systems: India must restructure its food policy architecture to prioritize dietary diversity by integrating pulses, millets, vegetables, and animal proteins into government schemes.

- This demands revisiting Minimum Support Price and procurement frameworks to incentivize nutrient-rich crops. PDS must evolve into a tool for nutritional security, not just caloric sufficiency.

- Linking agriculture with health goals ensures sustainable food systems. Such an approach also aligns with SDG 2.2 targets.

- Localized Nutrition Planning through District Nutrition Action Plans (DNAPs): Every district must formulate a data-driven Nutrition Action Plan aligned with local food cultures, agro-climatic conditions, and deficiencies.

- These plans can be anchored in Zila Parishads and monitored via Nutrition Dashboards. Institutional convergence through DM-led district nutrition committees will strengthen accountability.

- This decentralised strategy ensures context-sensitive interventions. It will also bridge the implementation gap across diverse geographies.

- Mainstream Soil-Health Linked Nutrition Strategy: A national framework linking soil health to human nutrition is needed, with targeted investments in soil organic carbon restoration and micronutrient balancing.

- Soil Health Cards must integrate nutrition outcome indicators. Promoting biofortification and agro-ecological practices can enhance the nutritive value of crops. This aligns agricultural policy with public health objectives.

- “From Soil to Stomach” must become a policy mantra.

- Soil Health Cards must integrate nutrition outcome indicators. Promoting biofortification and agro-ecological practices can enhance the nutritive value of crops. This aligns agricultural policy with public health objectives.

- Reinforce Frontline Nutrition Delivery through Ayushman Arogya Mandirs: Ayushman Arogya Mandirs should be equipped with dedicated nutrition counsellors to deliver personalized dietary advice, growth monitoring, and behaviour change communication.

- Expanding their role from curative to preventive nutrition services will help mainstream holistic wellness.

- HWCs must operate as convergence points for ICDS, WASH, and NCD screening.

- Mobile HWC units can serve remote and urban poor populations. This brings nutrition closer to people’s homes.

- Universal Fortification Beyond Staples with Region-Specific Nutrients: Food fortification must go beyond iron-folic rice and salt to include milk, edible oils, pulses, and condiments based on regional nutritional gaps.

- Encouraging decentralized, small-scale fortification through local SHGs and cooperatives can enhance reach and cultural acceptability. Nutrition-sensitive value chains must be supported with fiscal incentives.

- Fortified food supply should also expand to anganwadis, schools, and workplace canteens. This ensures a wider coverage of hidden hunger.

- Revamp Take-Home Ration (THR) into Customised Nutrition Kits: THR must be redesigned to meet age-specific and physiological requirements (children, adolescent girls, pregnant women).

- Local sourcing of ingredients through Farmer Producer Organisations (FPOs) and SHGs can improve freshness and reduce logistics costs. Integration with Poshan Vatikas and Ayurveda-based nutrition models adds value.

- Packaging should include instructions for use and preparation. This brings dignity and efficacy into government nutrition provisioning.

- Make Nutrition a Core Mandate in Education System: School curriculums should embed compulsory nutrition literacy modules from primary levels, covering balanced diets, food safety, and locally available healthy foods.

- Teachers should be trained in nutrition pedagogy and incentivised for conducting regular health-nutrition sessions.

- Collaboration with local cooks and mothers for meal planning adds contextual sensitivity. Schools should also act as demonstration sites for healthy dietary practices. Early awareness fosters lifelong impact.

- Create a Unified Nutrition Monitoring and Accountability Framework: A real-time National Nutrition Grid should be developed by integrating data from NFHS, POSHAN Tracker, PM-POSHAN, SHC, and HWC portals.

- This can track district-wise performance, service delivery, and outcomes simultaneously.

- Quarterly nutrition audits led by third-party institutions will ensure transparency. Integration with SDG dashboard and GHI score tracking will improve India’s global rankings. Data-driven decision-making becomes the bedrock of national nutrition policy.

- Integrate Nutrition with Climate-Resilient Food Systems: Nutrition security strategies must incorporate climate adaptation by promoting drought-resilient, nutrient-rich crops like millets, pulses, and tubers. Investments in agroforestry, integrated farming systems, and indigenous crop revival can diversify nutrition sources.

- Policy incentives for low-emission, high-nutrition food chains will serve dual goals.

- This aligns with India's commitment under SDG 13 and sustainable food systems under UNFSS. Nutrition must become climate-smart.

- Expand Private Sector Engagement through Nutrition-CSR Missions: Corporates should be mandated under CSR norms to invest in nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive interventions in their areas of operation.

- This includes workplace nutrition initiatives, supply chain fortification, mobile clinics, and mother-child support programs.

- Public-private partnerships in fortified food production and distribution must be scaled. Branding nutritional outreach can also reduce stigma. This brings scale, innovation, and sustainability into public nutrition efforts.

- Launch a Gender-Responsive Nutrition Budgeting Framework: Gender-sensitive budgeting must be applied across ministries (Health, WCD, Agriculture, Panchayati Raj) to ensure resources reach female-headed households, adolescent girls, and women farmers.

- Intersectional mapping of nutritional vulnerability will help target funds better. Conditional cash transfers for diet improvement should be expanded.

- Women must also be represented in nutrition governance at local levels. This ensures equity in access and empowerment.

Conclusion:

India’s progress in food production and distribution is remarkable, yet the battle against hidden hunger is far from over. Bridging the gap between food availability and nutritional adequacy demands a holistic, soil-to-stomach approach. As Mahatma Gandhi said, “It is health that is real wealth and not pieces of gold and silver.” Ensuring nutritional security is not just a policy goal—it is a moral imperative for a healthier, equitable future.

|

Drishti Mains Question: "Despite achieving food self-sufficiency and running the world’s largest food distribution programme, India continues to grapple with high levels of malnutrition." In this context, examine the role of soil health and food system reforms in ensuring nutritional security. |

UPSC Civil Services Examination, Previous Year Question (PYQ)

Prelims:

Q. Which of the following is/are the indicators/ indicators used by IFPRI to compute the Global Hunger Index Report? (2016)

- Undernourishment

- Child stunting

- Child mortality

Select the correct answer using the code given below:

(a) 1 only

(b) 2 and 3 only

(c) 1, 2 and 3

(d) 1 and 3 only

Ans: C

Mains:

Q. How far do you agree with the view that the focus on lack of availability of food as the main cause of hunger takes the attention away from ineffective human development policies in India? (2018)