Governance

Caste Census in India: Need and Challenges

- 07 May 2025

- 15 min read

For Prelims: National Commission for Backward Classes, Caste enumeration, Census, Scheduled Castes, Article 340

For Mains: Role of caste data in shaping affirmative action policies in India, Caste-based census

Why in News?

The Indian government has approved the inclusion of caste enumeration in the delayed Census 2021, reviving a practice discontinued after independence. Triggered by growing political and social demands, this move is expected to significantly impact governance, affirmative action, and social justice efforts.

What is a Caste Census?

- Definition: A caste census is a systematic collection of data on individuals’ caste identities during a nationwide population census.

- The word "caste" comes from the Spanish word 'casta', meaning 'race' or 'hereditary group'. The Portuguese used it to denote ‘Jati’ in India.

- M. N. Srinivas (Indian sociologist) defines caste as a hereditary, endogamous, and usually localized group, linked to a specific occupation, and occupying a certain position in the social hierarchy.

- Objective: It aims to understand the socio-economic distribution of various caste groups to inform policies on social justice, reservations, and welfare.

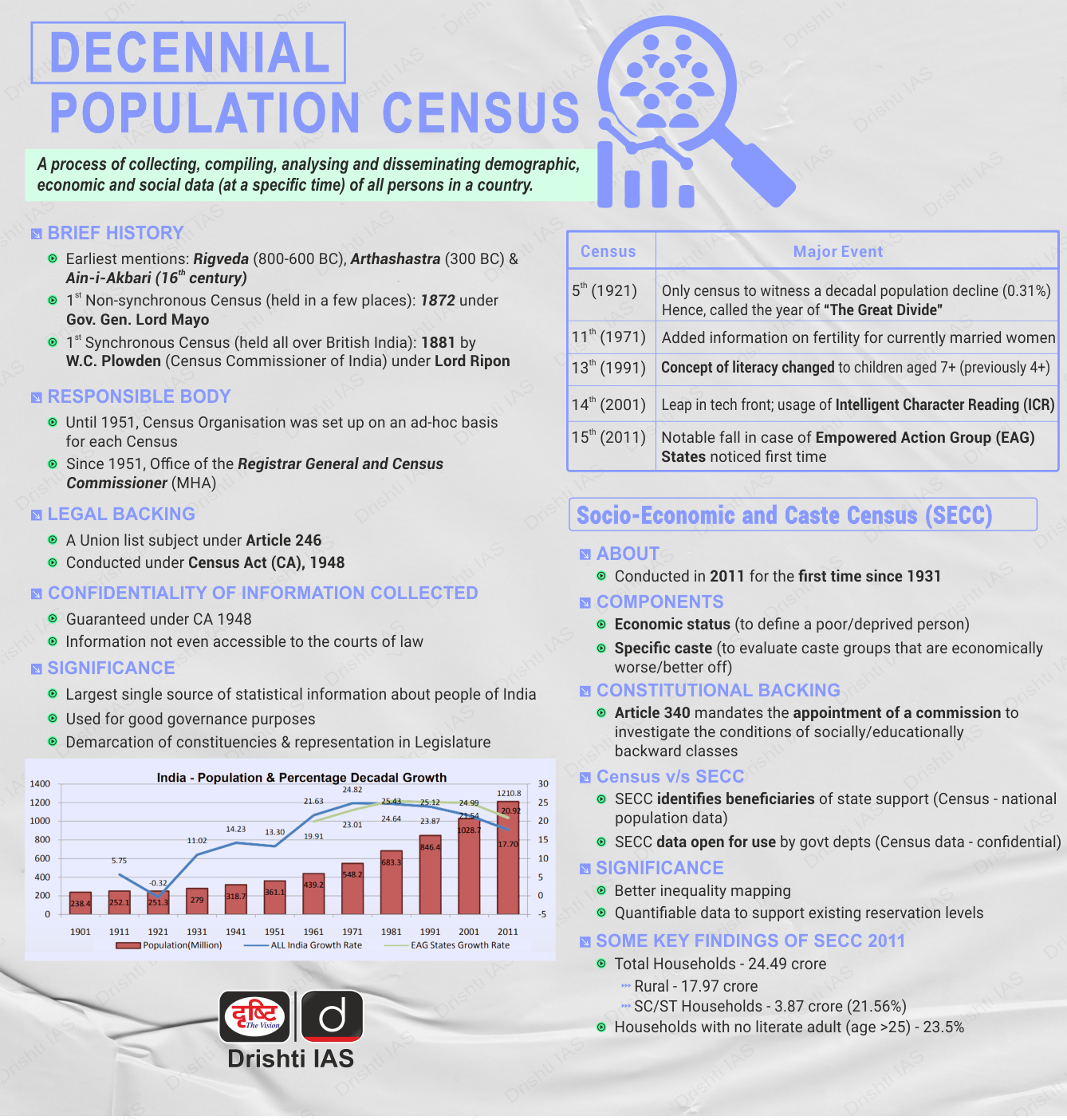

- Historical Context of Caste Enumeration: Caste enumeration was a regular feature of census exercises during British rule from 1881 to 1931, while the 1941 Census also collected caste information but did not publish it due to the onset of World War II.

- Since the 1951 Census, caste enumeration was discontinued for all except Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs), leaving no reliable national data on Other Backward Classes (OBCs) and other caste groups.

- In 1961, the central government allowed states to conduct surveys and compile state-specific lists of OBCs.

- The last national caste data collection was in 2011 through the Socio-Economic and Caste Census (SECC), aimed at assessing households' socio-economic conditions along with caste information.

- State-level Surveys: States like Bihar, Karnataka, and Telangana recently conducted their own caste surveys.

What is the Difference Between Caste Census and Caste Survey?Click Here to Read More: Caste Survey and Caste Census |

What is the Need for a Caste Census?

- Current Gap: While data exists for SCs and STs, there is no reliable, updated national data on OBCs and other caste groups, hindering effective policy formulation.

- Addressing Challenges from Previous Surveys: The 2011 SECC had significant flaws, particularly the lack of a comprehensive caste list.

- The National Commission for Backward Classes (NCBC), pointed out, the 2011 SECC proforma allowed citizens to enter any caste, leading to an overwhelming and inaccurate number of caste entries.

- This rendered the data unreliable and impractical. The upcoming caste census aims to address these issues by ensuring a more accurate and inclusive process.

- Reshaping Affirmative Action: The caste census can provide updated data to reassess reservation quotas and affirmative action programs.

- The absence of caste data has left OBC population estimates unclear; the last available data from the 1931 Census showed OBCs at 52%, which influenced the Mandal Commission’s 1980 reservation recommendations.

- Bihar's 2023 caste survey found OBCs and EBCs make up over 63% of the state's population, fueling calls for national-level caste data to guide policy decisions on reservations and social welfare.

- Sub-Categorization Within Broad Groups: Detailed data enables the sub-categorization of OBCs, as recommended by the Rohini Commission (2017), to ensure equitable distribution of reservation benefits.

- Political and Electoral Implications: Accurate caste data can lead to better political representation of marginalized groups, especially in state and national elections.

- Push for Equality and Inclusivity: Caste-based inequalities intersect with poverty, region, and gender.

- A caste census can highlight these disparities, aiding targeted policies. It is seen as a step toward addressing entrenched inequalities and creating more inclusive, equitable policies for diverse communities.

What are the Concerns Regarding a Caste Census in India?

- Risk of Reinforcing Caste Identities: Critics argue that a caste Census could entrench caste consciousness, legitimizing divisions rather than working toward a caste-less society.

- May deepen social segmentation and hierarchies, contradicting the constitutional goal of promoting fraternity and equality.

- Equity vs. Equality: While larger groups may benefit from representation, micro-quota fragmentation harms social cohesion.

- Disproportionately excludes minorities within the backward classes due to scale bias.

- Hyper-fragmentation risks undermining affirmative action meant for historically oppressed groups.

- Political Exploitation and Competitive Backwardness: Accurate caste data may fuel vote-bank politics, with parties tailoring policies for electoral gain.

- It could trigger demands for OBC/ST/SC status by politically dominant or upper caste groups, increasing pressures on reservation quotas.

- May lead to "competitive backwardness", where groups seek lower status for benefits.

- Constitutional and Legal Ambiguities: Though Article 340 permits the identification of backward classes, there is no constitutional mandate for caste enumeration in the general Census.

- Issues with Proportional Representation: Fresh caste data may challenge policies based on 1931 estimates, triggering demands for proportionate reservations and calls to revise the 51% cap set by the Indra Sawhney judgment, 1992.

- This shift might also encourage larger communities to seek greater benefits, undermining population control programs and affecting their effectiveness.

What are the Challenges in Conducting an Accurate Caste Census?

- Lack of a Standardized Caste List: A key challenge in conducting a caste Census is the lack of a standardized caste code list, no unified OBC list exists, the Central OBC list (used for central schemes) differs from more expansive state-specific lists.

- The SECC 2011’s open-ended self-reporting led to 46.7 lakh caste entries and over 8 crore errors, highlighting the difficulty of classifying India’s thousands of castes and sub-castes in a consistent, reliable manner.

- Caste Self-reporting and Mobility Claims: Individuals may claim affiliation with a higher caste due to its prestige, as seen in the colonial censuses where communities alternated between identifying as Kshatriya, Rajput, Brahmin, or Vaishya.

- In the post-independence period, some individuals may falsely identify with lower castes to gain benefits from reservations (e.g., some upper castes seeking OBC status).

- Caste identities are often fluid, and self-reporting can vary across regions or generations.

- Misclassification of Castes: Confusion Due to similar surnames like ‘Dhanak’, ‘Dhankia’, ‘Dhanuk’, and ‘Dhanka’ belong to different caste categories (SC, ST, etc.), leading to errors.

- Additionally, differing classifications across states further complicate the census, for example, the Meena community is classified as ST in Rajasthan but as OBC in Madhya Pradesh.

- Given the sensitivity of caste in India, enumerators may avoid direct questions and rely on assumptions based on surnames, often leading to inaccurate entries.

- Institutional and Administrative Capacity Constraints: The Census lacks a dedicated verification and coding unit, which may lead to the new caste census data being as unreliable as the SECC 2011 data.

What Measures Can Ensure the Credibility and Accuracy of a Caste Census in India?

- Listing Castes: The first step is to list the castes and communities to be enumerated, considering differing classifications across states. The Registrar General of India and Census Commissioner must consult with academics, caste groups, political parties, and the public to finalize this list.

- Without this, there is a risk of repeating the inconsistencies observed in the 2011 census.

- Data Verification and Grievance Redressal: To improve caste census credibility, integrating Aadhaar can help reduce duplication and ensure accurate identity verification.

- A multi-tier verification mechanism should be established to reduce classification errors, complemented by a transparent grievance redressal system for resolving disputes and misclassifications. Additionally, involving community-level oversight will strengthen local validation and foster public trust in the enumeration process.

- Leverage Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning for accurate data sorting and analysis.

- Sub-categorization for Equity: Implement Justice Rohini Commission's recommendations for sub-categorizing OBCs.

- Aligning with the Supreme Court judgment in State of Punjab v. Davinder Singh (2024), sub-classify SCs and STs within the reservation quota based on varying levels of backwardness, using empirical data and historical evidence.

- Ensure more equitable distribution of reservation benefits and representation among various sub-groups.

- Socio-Economic Integration: Supplement caste data with indicators like the Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI).

- The Tendulkar Committee (2009) found that 29% of below poverty line (BPL) cardholders are poor, while 13% of Above Poverty Line (APL) cardholders are poor.

- This calls for revising outdated poverty measures and conducting an effective socio-economic census to address inclusion and exclusion errors.

- Focus on regional disparities; allow states the flexibility to design welfare schemes beyond a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach.

- The Tendulkar Committee (2009) found that 29% of below poverty line (BPL) cardholders are poor, while 13% of Above Poverty Line (APL) cardholders are poor.

- Ensuring Fair Usage and Avoiding Political Misuse: Treat the caste census as a tool for inclusive development, not vote-bank politics. Use data to rationalize existing policies and target the most disadvantaged.

- Monitor and evaluate policies implemented using census data to ensure intended outcomes.

Conclusion

The caste census marks a pivotal shift in India's data-driven governance, aiming to bridge historical gaps in representation and welfare. While it promises inclusivity and better policy targeting, concerns around accuracy, politicization, and social harmony must be addressed. Robust safeguards and transparent execution, in line with Sustainable Development Goal 16 (enabling data-driven governance), will be key to its success.

|

Drishti Mains Question: A caste census can serve as a powerful tool for social justice, but it also risks reinforcing social divisions. Discuss |

UPSC Civil Services Examination, Previous Year Question

Prelims

Q. Consider the following statements: (2009)

- Between Census 1951 and Census 2001, the density of the population of India has increased more than three times.

- Between Census 1951 and Census 2001, the annual growth rate (exponential) of the population of India has doubled.

Which of the statements given above is/are correct?

(a) 1 only

(b) 2 only

(c) Both 1 and 2

(d) Neither 1 nor 2

Ans: (d)

Exp:

- One of the important indices of population concentration is the density of population. It is defined as the number of persons per square kilometre.

- The population density of India in 2001 was 324 persons per square kilometre and in 1951 it was 117. Thus, the density increased more than twice, but not thrice. Hence, statement 1 is not correct.

- At the beginning of the twentieth century, i.e., in 1901 the density of India was as low as 77 and this steadily increased from one decade to another to reach 324 in 2001.

- The average Annual Growth Rate in 2001 was 1.93 whereas in 1951 it was 1.25. Thus, it increased, but not doubled. Hence, statement 2 is not correct. Therefore, option (d) is the correct answer.

Mains

Q. Why is caste identity in India both fluid and static? (2023)

Q. Has caste lost its relevance in understanding the multi-cultural Indian Society? Elaborate your answer with illustrations. (2020)

Q. “Caste system is assuming new identities and associational forms. Hence, the caste system cannot be eradicated in India.” Comment. (2018)