Indian Polity

Issue of Naga Insurgency

- 08 Sep 2020

- 14 min read

This editorial analysis is based on the article The search for an end to the complex Naga conflict which was published in The Hindu on 8th of September 2020. It analyses the issue of Naga insurgency and the issues related to it.

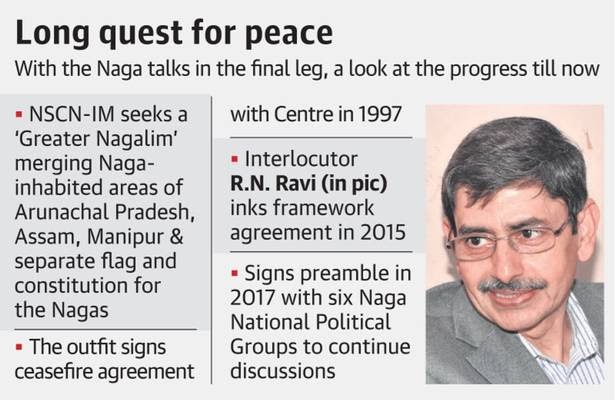

The Naga peace process appears to have again hit a roadblock after decades of negotiations. The non-flexibility of the National Socialist Council of Nagaland (NSCN-IM) on the “Naga national flag” and “Naga Yezhabo (constitution) among many more are said to be the primary reasons. But the issue is more complex than the twin conditions, as it affects Nagaland’s neighbours in northeast India.

How did it start?

- The Naga Hills became part of British India in 1881.

- The effort to bring scattered Naga tribes together resulted in the formation of the Naga Club in 1918.

- The Naga club rejected the Simon Commission in 1929 and asked them “to leave us alone to determine for ourselves as in ancient times”.

- The club metamorphosed into the Naga National Council (NNC) in 1946.

- Under the leadership of Angami Zapu Phizo, the NNC declared Nagaland as an independent State on August 14, 1947, and conducted a “referendum” in May 1951 to claim that 99.9% of the Nagas supported a “sovereign Nagaland”.

- On March 22, 1952, Phizo formed the underground Naga Federal Government (NFG) and the Naga Federal Army.

- The government of India sent in the Army to crush the insurgency and, in 1958, enacted the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act.

- In 1975, when the government signed the Shillong Accord, under which this section of NNC and NFG agreed to give up arms.

- A group of about 140 members led by Thuingaleng Muivah, who was at that time in China, refused to accept the Shillong Accord and formed the National Socialist Council of Nagaland (NSCN) in 1980.

- Muivah also had Isak Chisi Swu and S S Khaplang with him.

- In 1988, the NSCN split into NSCN (IM) and NSCN (K) after a violent clash.

- While the NNC began to fade away, and Phizo died in London in 1991, the NSCN (IM) came to be seen as the “mother of all insurgencies” in the region.

The History of Peace Process

- In June 1947, Assam Governor Sir Akbar Hydari signed the Nine-Point Agreement with the moderates in the NNC but the main leaders of the movement like Phizo were not taken into confidence and hence Phizo rejected it outrightly.

- A 16-point Agreement followed in July 1960 leading to the creation of Nagaland on December 1, 1963. In this case, the agreement was with the Naga People’s Convention that moderate Nagas formed in August 1957 during a violent phase and not with the NNC.

- In April 1964, a Peace Mission was formed for an agreement on suspension of operations with the NNC, but it was abandoned in 1967 after six rounds of talks.

- On November 11, 1975, the government signed the Shillong Accord, under which this section of NNC and NFG agreed to give up arms.

- However, a faction within the group refused to accept the Shillong Accord and formed the National Socialist Council of Nagaland in 1980.

Naga Peace Process Under Different Prime Ministers

- The Nagas had been demanding sovereignty even before India’s independence, claiming that they had not been part of British India.

- Pandit Nehru rejected the demand, but he kept Naga matters under a director in the ministry of external affairs.

- Indira Gandhi offered them “anything but independence”, but transferred the issue to the home ministry, further angering the Nagas.

- The first olive branch from an Indian Prime Minister was waived by P.V. Narasimha Rao.

- His government secretly talked with the NSCN-IM and the same was followed by H.D. Deve Gowda.

- Indra Kumar Gujaral was able to conclude a ceasefire agreement with them but it failed to conclude a long-lasting peace.

- Atal Bihari Vajpayee recognised the “unique history and the situation of the Nagas” and created a ceasefire monitoring group in 2001.

- Manmohan Singh also tried to negotiate with the NSCN-IM but nothing could be finalised.

- The incumbent government and the National Socialist Council of Nagalim (Isak-Muivah), or the NSCN-IM, had signed a Naga Peace Accord in August 2015 which was claimed a historic achievement at that time. But a final accord has remained elusive since then.

The Hurdle

- Recognition of Naga sovereignty, integration of all Naga-speaking areas into a Greater Nagaland, Separate Constitution and Separate Flag are the demands that the union government may find difficult to fulfil.

- The current demands of the NSCN (IM) have toned down from complete sovereignty to greater autonomous region within the Indian constitutional framework with due regard to the uniqueness of Naga history and traditions.

- However, negotiations with the NSCN-IM have remained complicated, as Nagas are demanding the integration of their ancestral homelands, which include territories in Assam, Manipur and Arunachal Pradesh.

- All three states have refused to cede territory to the Nagas.

- Manipur has protested in a petition that any compromise with Manipur’s territorial integrity would not be tolerated.

- The other two States have made it clear that they won’t compromise with their territorial integrity.

- Another significant issue is how the weapons in the NSCN-IM camps are going to be managed. As a ‘ceasefire’ group, its cadres are supposed to retain their weapons inside the designated camps for self-defence only, but more often than not, many influential cadres are seen moving with weapons in civilian localities, leading to many problems.

- It would be an uphill task for the Centre to ensure that all weapons are surrendered at the time of the final accord.

- In the early phase, the Naga insurgents were provided with what has come to be known as ‘safe haven’ in Myanmar.

- India’s adversaries (China and Pakistan) also provided them with vital external support at one point in time.

- The porous border and rugged terrain make it different for the Security Forces as they cross borders where they are sheltered and fed.

Immediate Stalemate

- A letter written by the Governor to the CM of Nagaland has become the latest irritant.

- Mr. R.N. Ravi, the Governor had expressed his anguish over the culture of extortion and the collapse of general law and order situation in Nagaland, where organised armed gangs run their own parallel ‘tax collection’ regimes.

- Extortions in the name of taxes have been a thorny facet of the Naga issue.

- The ‘taxes’ levied by insurgent groups are intricately intertwined in almost all developmental activities in Nagaland and one of the major aims of the NSCN-IM has been to acquire formal recognition of this informal practice through negotiations.

Other Side’s Story

- A section of people in Nagaland has criticized the Governor for approaching Nagaland like a "law and order issue" instead of a political one.

- They claim that the government would not have signed a framework agreement with NSCN-IM in 2015 if Nagaland was a “law and order issue."

- Misunderstandings surrounding the history and identity of the Naga people have further complicated the negotiations.

- The Central Government views Nagaland as a "disturbed area" and has kept the state under a draconian Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA).

- The act extends wide-ranging powers to the army, including the use of force and arrests without warrants.

Way Forward

- The Centre must negotiate with all the factions and groups of the Insurgents to have a long-lasting peace.

- The Government too realised that privileging one insurgent group could eventually distort the contours of the final peace accord and it subsequently enlarged the peace process by roping in seven other Naga insurgent groups under the umbrella of Naga National Political Groups (NNPG).

- However, another important group, the NSCN- Khaplang, whose cadres are reported to be inside Myanmar, is still outside the formal process.

- Nagas are culturally heterogeneous groups of different communities/tribes having a different set of problems from the mainstream population.

- In order to achieve the long-lasting solution, their cultural, historical and territorial extent must be taken into consideration.

- Another way of dealing with the issue can be maximum decentralisation of powers to the tribal heads and minimum centralisation at the apex level, which should mainly work towards facilitating governance and undertaking large development projects.

- For any peace framework to be effective, it should not threaten the present territorial boundaries of the states of Assam, Manipur and Arunachal Pradesh. As it will not be acceptable to these states.

- Greater autonomy for the Naga inhabited areas in these states can be provided which would encompass separate budget allocations for the Naga inhabited areas with regard to their culture and development issues.

- A new body should be constituted that would look after the rights of the Nagas in the other north-eastern states besides Nagaland.

- Moreover, the Centre must keep in mind that most of the armed insurgencies across the world do not end in either total victory or comprehensive defeat, but in a grey zone called ‘compromise’.

Nagas

- Nagas are a hill people who are estimated to number about 2. 5 million (1.8 million in Nagaland, 0.6 million in Manipur and 0.1 million in Arunachal states) and living in the remote and mountainous country between the Indian state of Assam and Burma.

- There are also Naga groups in Burma.

- The Nagas are not a single tribe, but an ethnic community that comprises several tribes who live in the state of Nagaland and its neighbourhood.

- Nagas belong to the Indo-Mongoloid Family.

- There are nineteen major Naga tribes, namely, Aos, Angamis, Changs, Chakesang, Kabuis, Kacharis, Khain-Mangas, Konyaks, Kukis, Lothas (Lothas), Maos, Mikirs, Phoms, Rengmas, Sangtams, Semas, Tankhuls, Yamchumgar and Zeeliang.

|

Drishti Mains Question Critically analyse the Naga Conundrum and the reasons responsible for it. How can an everlasting peace in Nagaland be ensured? |

This editorial is based on “Mission Karmayogi shouldn't become an exercise of political vindictiveness” which was published in the Business Standard on September 4th, 2020. Now watch this on our Youtube channel.