US Retreat from Multilateralism

For Prelims: Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), Paris Agreement 2015, World Health Organization (WHO), UN Human Rights Council (UNHRC), UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), UN Population Fund (UNFPA), International Solar Alliance (ISA), Coalition for Disaster Resilient Infrastructure (CDRI), Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanisms (CBAM), National Green Hydrogen Mission (NGHM) 2023, Small Modular Reactors (SMRs)

For Mains: Implications of US withdrawal from international organizations and agreements, and steps needed by India to overcome these challenges.

Why in News?

The US has withdrawn from 66 international organisations, including 31 UN bodies, citing national interest considerations under the “America First” approach—echoing similar exits during the earlier Trump presidency.

- By stepping away from key climate institutions such as the UNFCCC, the US risks weakening global climate governance and constraining climate finance for developing countries.

What are the Likely Implications of US Withdrawal from International Bodies?

- Geopolitical and Strategic Vacuum: China has systematically increased representation in UN technical bodies (ITU, FAO, ICAO). US withdrawal removes a counterbalancing veto-player, not just a voice.

- Historically, similar actions (e.g., US withdrawal from UNESCO in 2017, later reversed) led to a 22% funding gap in that organization.

- Climate Governance & Finance: Withdrawing from the UNFCCC would legally remove the US, the largest cumulative emitter (around 24% of historical CO₂), from the climate treaty, ending its formal role in shaping critical COP rules. This move would also damage its international reputation, making it harder to negotiate effectively in other unrelated areas.

- This exit risks giving cover to other reluctant governments and hardening the positions of developing countries who see it as a failure of leadership from a top current emitter (12.7% of global CO₂ in 2024).

- Adaptation finance is already far below the estimated USD 310–365 billion per year, and reduced US willingness to contribute can worsen North–South trust asymmetry and harden developing country positions in negotiations.

- Peacebuilding/Human Security Spillovers: The US withdrawal from UN peacebuilding mechanisms undermines its security goals and risks destabilization that can create future security threats requiring costlier military solutions. By cutting funding for efforts addressing health, climate displacement, and conflict prevention, it endangers human rights and may exacerbate climate-induced migration for up to 200 million people by 2050.

- Economic/Trade Competitiveness: US exporters become more exposed to foreign climate-linked trade measures, such as carbon border adjustments, as the US forfeits its role in shaping these international norms. This raises the overall “cost of doing climate business” and risks isolating US industry from evolving global standards.

- Reduced Aid and Technical Assistance: US withdrawals from UN bodies often correlate with aid cuts, such as the 2017 defunding of the UN Population Fund (UNFPA), which impacted reproductive health programs in Africa and Asia. Furthermore, exits from science and education bodies restrict vital technology transfer to the Global South.

Major International Organizations and Agreements from Which the United States has Withdrawn

- UN Treaties and Climate Bodies:

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC): The core global climate treaty underpinning COP negotiations and the Paris Agreement 2015.

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC): The world’s leading scientific body assessing climate change.

- Climate, Environment, and Biodiversity Institutions:

- International Solar Alliance (ISA): India-led initiative that promotes global cooperation on solar energy.

- International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN): Global authority on biodiversity conservation.

- Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES): Assesses biodiversity and ecosystem health.

- UN Collaborative Programme on Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD+): Combat climate change by making forests more valuable standing than cut down.

- UN Energy: Coordinates UN system-wide energy-related work.

- Intergovernmental Forum on Mining, Minerals, Metals, and Sustainable Development: Works closely with the UN on sustainable mining.

- Demography and Electoral Bodies:

- UN Population Fund (UNFPA): Focuses on reproductive health, population data, and gender equality.

- International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (IDEA): Supports democratic institutions and processes.

- Security and Counter-Terrorism: Global Counter-Terrorism Forum (GCTF), a multilateral platform for counter-terrorism cooperation.

- Previously Withdrawn: Paris Agreement, World Health Organization (WHO), UN Human Rights Council (UNHRC) and UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).

How can India Respond to the US Withdrawal from Multilateral Institutions?

- Lead Climate Coalitions Proactively: India should move from participation to agenda-setting leadership in platforms like the International Solar Alliance (ISA) and the Coalition for Disaster Resilient Infrastructure (CDRI), helping sustain global climate momentum amid US disengagement.

- Secure Alternative Climate Finance: To counteract likely frozen US contributions to the Green Climate Fund (GCF) and Global Environment Facility (GEF), India must diversify its climate finance by aggressively pitching projects to other donors (EU, UK, Japan, Nordic countries) and blending finance from multilateral development banks (MDBs).

- Build Resilience to Carbon Border Measures: Anticipating that the US exit may accelerate EU-style Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanisms (CBAM), India must decarbonize key export sectors like steel, cement, and aluminium by accelerating its National Green Hydrogen Mission (NGHM) 2023 and Carbon Credit Trading Scheme (CCTS).

- Become a Green Tech Hub: Aim for Atmanirbharta by scaling up PLI schemes for solar PV, batteries, and electrolyzers, and by becoming a global exporter of IAEA-safeguarded small modular reactors (SMRs) as a low-carbon baseload alternative.

- Invest in Science, Technology, and Innovation: To counter reduced US involvement, India must strengthen climate science networks and support technology transfer in green hydrogen, battery storage, and carbon capture. It must also significantly increase its public and private R&D expenditure in climate technology to drive innovation and competitiveness.

Conclusion

The US withdrawal from multilateral bodies creates a vacuum in global governance, jeopardizing climate action, finance, and security. India must respond by championing reformed multilateralism, leading climate coalitions, securing alternative finance, and enhancing green-tech self-reliance to protect its national interests and those of the Global South.

|

Drishti Mains Question: How does US disengagement from multilateral institutions reshape global geopolitics and climate finance architecture? |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why is the US withdrawal from UNFCCC problematic?

It removes the world’s largest cumulative emitter (around 24% historical CO₂) from the core legal framework governing COP negotiations and Paris Agreement implementation.

2. How does US exit affect climate finance for developing countries?

It weakens funding predictability for mechanisms like the GCF and GEF, impacting adaptation, mitigation, and loss-and-damage finance.

3. What are the geopolitical consequences of US withdrawal?

It creates a leadership vacuum in global governance, allowing rivals like China to gain agenda-setting influence in UN institutions.

UPSC Civil Services Examination Previous Year Question (PYQ)

Prelims

Q. With reference to the Agreement at the UNFCCC Meeting in Paris in 2015, which of the following statements is/are correct? (2016)

- The Agreement was signed by all the member countries of the UN, and it will go into effect in 2017.

- The Agreement aims to limit the greenhouse gas emissions so that the rise in average global temperature by the end of this century does not exceed 2ºC or even 1.5ºC above pre-industrial levels.

- Developed countries acknowledged their historical responsibility in global warming and committed to donate $ 1000 billion a year from 2020 to help developing countries to cope with climate change.

Select the correct answer using the code given below:

(a) 1 and 3 only

(b) 2 only

(c) 2 and 3 only

(d) 1, 2 and 3

Ans: (b)

Mains

Q. Describe the major outcomes of the 26th session of the Conference of the Parties (COP) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). What are the commitments made by India in this conference? (2021)

Q. Explain the purpose of the Green Grid Initiative launched at the World Leaders Summit of the COP26 UN Climate Change Conference in Glasgow in November 2021. When was this idea first floated in the International Solar Alliance (ISA)? (2021)

Age of Consent and Adolescent Autonomy

For Prelims: Supreme Court of India, Age of Consent, Protection of Children from Sexual Offenses (POCSO) Act, 2012

For Mains: Child rights and protection laws in India, Adolescent autonomy and evolving capacities

Why in News?

In State of Uttar Pradesh versus Anurudh & Anr. (2026), the Supreme Court of India flagged the rising use of the Protection of Children from Sexual Offenses (POCSO) Act, 2012 in cases involving consensual adolescent relationships.

- Noting that a law meant to protect children from sexual abuse is often invoked by families against young couples when one partner is under 18, the Court urged the Union government to consider corrective measures.

- This observation has revived the long-standing debate on whether India should reconsider the age of consent.

Summary

- The Supreme Court’s observations highlight how the POCSO Act, while aimed at child protection, is increasingly used in cases of consensual adolescent relationships, raising concerns of over-criminalisation and mismatch with social realities.

- The debate calls for a balanced, nuanced approach that protects children from exploitation while recognising adolescent autonomy through judicial clarity, targeted legal safeguards, and stronger emphasis on education and support systems.

What Does “Age of Consent” Mean under Indian Law?

- Age of Consent: It is the legally fixed age at which a person is considered capable of consenting to sexual activity. In India, this age is 18 years, under the gender-neutral POCSO Act, 2012.

- Anyone below 18 is legally treated as a “child”, and their consent has no legal validity. Sexual activity with a minor is automatically classified as statutory rape, regardless of willingness.

- Section 19 of POCSO Act, 2012 makes reporting mandatory for anyone who knows or even suspects an offence.

- Legal Evolution: In India age of consent was originally fixed at 10 years under the Indian Penal Code (IPC), 1860 then raised to 12 by the Age of Consent Act, 1891, and subsequently increased to 14 and later 16.

- In 2012, the POCSO Act raised the age of consent to 18 years, and this position was reinforced by the Criminal Law (Amendment) Act, 2013, which aligned the IPC’s rape provisions with the POCSO framework.

- This standard has been retained under the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023, where Section 63 defines rape to include sexual acts with or without consent if the woman is below 18 years of age.

- Notably, the age of consent is distinct from the minimum age of marriage, which remains 18 years for women and 21 years for men under Prohibition of Child Marriage Act, 2006.

- Judicial Views:

- State v. Hitesh (2025), Delhi High Court: The Court held that the law should recognise consensual romantic relationships among adolescents and respect their autonomy, provided such relationships are free from coercion, exploitation, or abuse.

- It emphasised the need for legal and societal approaches to evolve in line with adolescent realities.

- Ashik Ramjaii Ansari v. State of Maharashtra (2023), Bombay High Court: The Court ruled that sexual autonomy includes both the right to engage in consensual sexual activity and the right to protection from sexual aggression, and that recognising both is essential to uphold human dignity.

- Mohd. Rafayat Ali v. State of Delhi, Delhi High Court (2025): The Court reaffirmed that under the POCSO Act, consent is legally irrelevant if the victim is below 18 years, and any sexual act with a minor constitutes an offence irrespective of willingness.

- State v. Hitesh (2025), Delhi High Court: The Court held that the law should recognise consensual romantic relationships among adolescents and respect their autonomy, provided such relationships are free from coercion, exploitation, or abuse.

What are the Arguments Regarding the Lowering the Age of Consent?

Arguments in Favour

- Recognition of Adolescent Autonomy: Adolescents aged 16–18 are increasingly capable of making informed choices about relationships due to greater access to education, awareness of rights, exposure to digital information, and improved cognitive maturity, yet the current law overlooks their evolving capacity for consent.

- Fourth National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4) shows that 39% of Indian girls had their first sexual experience before 18, while Enfold and Project 39A studies (2016–20) found that about one-fourth of POCSO cases involved consensual adolescent relationships, making the law out of sync with ground realities.

- Misuse of POCSO in Consensual Relationships: A significant number of POCSO cases involve consensual romantic relationships between teenagers, often triggered by parental disapproval rather than sexual exploitation.

- The blanket 18-year threshold turns consensual intimacy into statutory rape, leading to arrest, incarceration, and long trials that harm both the boy and the girl.

- International practices: Many countries set the age of consent at 16 and provide “close-in-age” exemptions to avoid criminalising peers in consensual relationships.

- Shift towards Education Rather than Punishment: Supporters argue that comprehensive sex education and awareness are more effective than criminal law in ensuring safe adolescent behaviour.

- Need for a Nuanced Legal Approach: Advocates suggest recognising consent for those above 16 while retaining safeguards against coercion, exploitation, or abuse of authority.

Arguments Against

- Protection of Children from Exploitation: Lowering the age risks weakening safeguards against sexual abuse, trafficking, and coercion, particularly in a society with deep power imbalances.

- Consent May be Illusory: A 2007 study by the Ministry of Women and Child Development found over 50% of abusers were known to the child (family members, teachers, neighbours), where apparent consent may actually be the result of fear, manipulation, or dependency.

- A strict age threshold acts as a strong deterrent against adult predators who may otherwise exploit minors under the guise of consent.

- Risk of Silencing Victims: Diluting the POCSO could discourage reporting and legitimise coercive behaviour, undermining child protection goals.

- Parliamentary and Expert Opposition: Parliamentary Standing Committees (2011, 2012) opposed recognising minor consent or close-in-age exemptions.

- Law Commission (283rd Report, 2023) warned that lowering the age would make POCSO ineffective and weaken efforts against child marriage, prostitution, and trafficking.

- Broader social consequences: Concerns exist that reducing the age may encourage premature sexual activity without adequate emotional maturity or social support.

What Measures can Strengthen Child Safety and Protection While Reconsidering the Age of Consent?

- Legislative Domain with Judicial Guidance: While any change in the age of consent lies within Parliament’s domain, the Supreme Court of India must clarify the growing interpretational divide between statutory law and High Court rulings to ensure uniform application by police and lower courts.

- Need for a Holistic Response: Legal reform alone cannot address adolescent realities and must be supported by sex education, accessible health services, gender-sensitive policing, and family and community support, particularly for adolescent girls who often face parental opposition in matters of choice and relationships.

- Focus on Differentiation, not Dilution: Instead of a mechanical debate over whether the age of consent should be 16 or 18, the law should be reshaped to prioritise child protection by clearly distinguishing consensual, age-appropriate peer relationships from situations involving coercion, power imbalance, or exploitation, ensuring justice without over-criminalisation.

- Allow consensual relationships among 16–18-year-olds within a narrow age gap, such as 3–4 years. Mandatory judicial scrutiny can help identify abuse or power imbalance.

- Build an Empathetic Framework: The goal should be protection without over-criminalisation. A balanced approach can safeguard children while respecting adolescent autonomy and dignity.

Conclusion

The age of consent debate calls for balance, not extremes. The law must protect children from exploitation while avoiding the criminalisation of consensual adolescent relationships through a more nuanced and empathetic approach.

|

Drishti Mains Question: The misuse of the POCSO Act in consensual adolescent relationships reflects a gap between law and social reality. Examine. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the age of consent under Indian law?

It is 18 years under the POCSO Act, 2012, and any sexual act with a minor is treated as statutory rape, irrespective of consent.

2. Why is POCSO criticised in consensual adolescent cases?

Many cases involve consensual relationships between teenagers, often reported by disapproving families, leading to over-criminalisation.

3. What did the Supreme Court observe in Anurudh (2026)?

The Supreme Court of India noted rising misuse of POCSO in consensual adolescent relationships and urged corrective measures.

4. What is a ‘close-in-age’ exemption?

It allows consensual relationships between adolescents within a narrow age gap, while still protecting against coercion and exploitation.

UPSC Civil Services Examination Previous Year Question (PYQ)

Q. With reference to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, consider the following: (2010)

- The Right to Development

- The Right to Expression

- The Right to Recreation

Which of the above is/are the Rights of the child?

(a) 1 only

(b) 1 and 3 only

(c) 2 and 3 only

(d) 1, 2 and 3

Ans: (d)

Conservation of Grasslands

For Prelims: Grasslands, UNFCCC, International Year of Rangelands and Pastoralists (IYRP), Carbon sinks, Sustainable Development Goals

For Mains: Grasslands as carbon sinks and their role in climate mitigation, Forest-centric bias in global and national climate policies, Institutional and legal gaps in grassland conservation in India

Why in News?

Grasslands remain underrepresented in global and national climate plans, as discussions at the UNFCCC COP30 continued to prioritise forests, even as the United Nations declared 2026 as the International Year of Rangelands and Pastoralists (IYRP).

Summary

- Grasslands are critical for climate regulation, biodiversity, and livelihoods, yet remain underrepresented in climate and conservation policies due to forest-centric approaches, institutional silos, and weak legal protection.

- Recognising grasslands as distinct ecosystems, integrating them into climate commitments, and empowering pastoral communities—especially under IYRP 2026—is essential for sustainable and inclusive ecosystem governance.

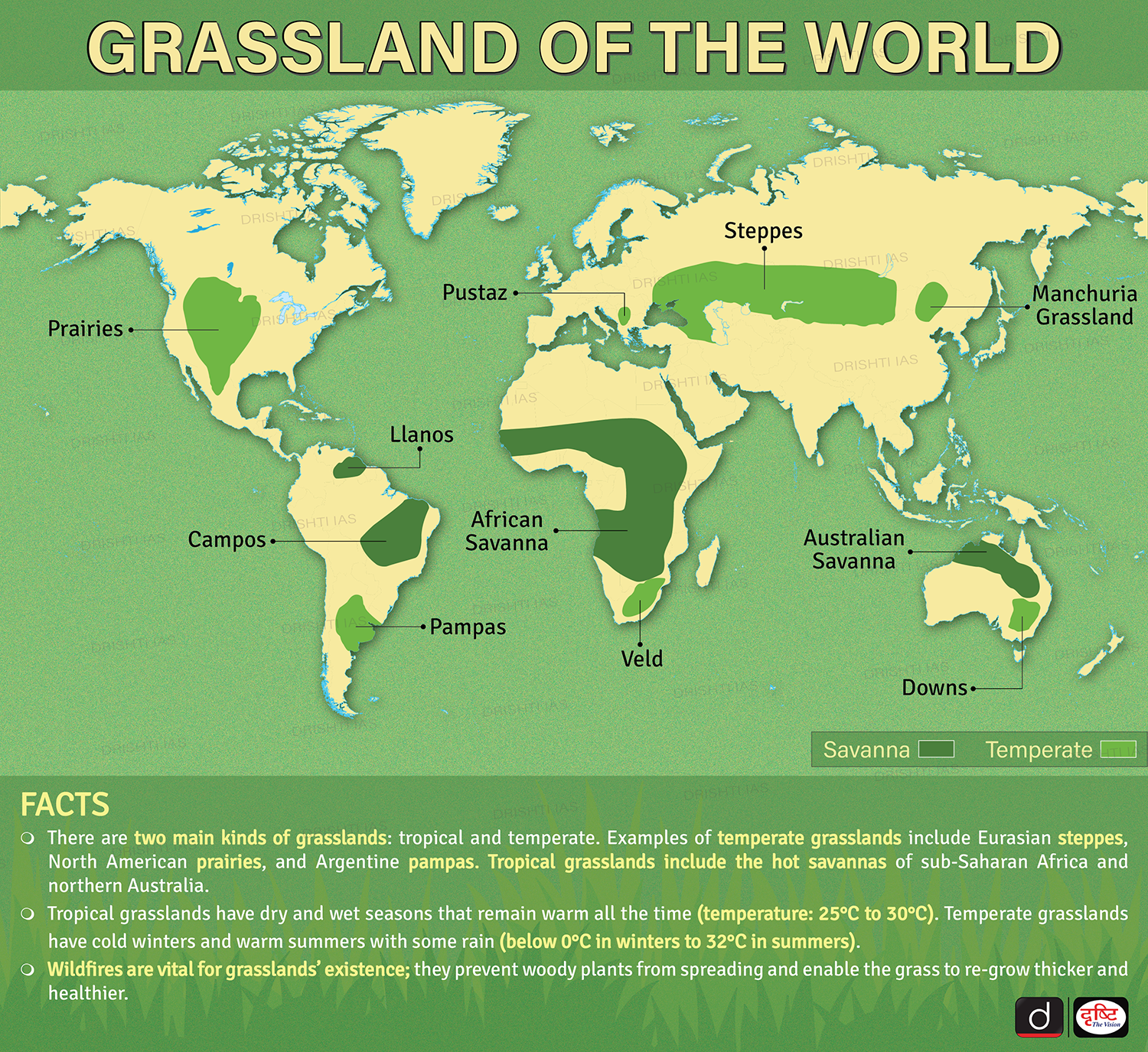

What are Grasslands?

- About: Grasslands are open terrestrial ecosystems dominated by grasses, with sparse or no tree cover, adapted to seasonal droughts, grazing, and fires. They include savannas, rangelands, and pasture commons.

- UNESCO defines them as land with less than 10% tree and shrub cover, while wooded grasslands have 10–40% cover.

- Grasslands are among the largest ecosystems, covering about 40.5% of Earth’s terrestrial area (excluding Greenland and Antarctica), far exceeding the extent of woody savannahs, shrublands, and tundra.

- They play a crucial ecological role, with tropical and sub-tropical grasslands storing nearly 15% of global terrestrial carbon.

- They support the livelihoods of around 20% of the world’s population, especially pastoral and agro-pastoral communities, and rely on natural disturbance regimes such as fire and grazing to maintain biodiversity and ecosystem balance.

- Grasslands in India: They occupy about 24% of India’s geographical area, yet they have witnessed severe decline over time.

- Major grassland regions in India are found in Rajasthan, Gujarat, Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, Karnataka, Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, the Terai–Duar belt of Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Assam and West Bengal, and the alpine grasslands of Himachal Pradesh and Ladakh.

- Banni Grassland, located in Kutch district of Gujarat, is the largest grassland in Asia.

- Despite their ecological and livelihood value, less than 1% of India’s grasslands are protected under the formal conservation network.

- Role of Grasslands:

- Climate Regulation: Act as major carbon sinks, especially tropical grasslands, helping mitigate climate change.

- Livelihood Support: Sustain pastoral and agro-pastoral communities by providing grazing land, fodder, fuel, and food.

- Biodiversity Conservation: Serve as habitats for diverse plant species, birds, and grassland-dependent wildlife.

- Water & Soil Regulation: Aid groundwater recharge, reduce soil erosion, and regulate local hydrology.

- Ecosystem Stability: Depend on natural fire and grazing regimes that maintain ecological balance and resilience.

Note: The United Nations General Assembly declared 2026 as the International Year of Rangelands and Pastoralists, led by the Food and Agriculture Organization.

- Rangelands consisting of grasslands, savannahs, deserts, and shrublands, are vital for biodiversity, ecosystem regulation, and climate resilience.

- Rangelands cover over half of the Earth’s land surface and support more than 500 million pastoralists (communities that depend on rangelands for herding livestock).

- The initiative seeks to raise awareness, promote responsible investment, secure pastoralists’ land and mobility rights, strengthen inclusive governance, and improve rangeland management, contributing to sustainable livelihoods and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

What are the Gaps in Grassland Conservation?

- Misclassification and Policy Blindness: Grasslands are routinely labelled as degraded forests or wastelands, leading to afforestation, plantations, or diversion for infrastructure, despite being natural, biodiversity-rich ecosystems.

- Indian grasslands are governed by nearly 18 ministries with conflicting mandates. The Environment Ministry treats them as afforestation targets, while the Rural Development Ministry labels many as “wastelands”.

- This policy fragmentation leads to misclassification and weak protection of grasslands.

- Indian grasslands are governed by nearly 18 ministries with conflicting mandates. The Environment Ministry treats them as afforestation targets, while the Rural Development Ministry labels many as “wastelands”.

- Institutional Silos: Climate action (UNFCCC), biodiversity (Convention on Biological Diversity), and land degradation (UN Convention to Combat Desertification) are handled separately, preventing integrated ecosystem protection and leaving grasslands trapped in governance gaps.

- Despite the UN Convention to Combat Desertification (COP16) formally recognising rangelands as complex socio-ecological systems and Resolution L15 calling for prioritised investment and improved land-tenure security, grasslands still lack a dedicated legal framework, unlike forests and wetlands.

- In India, laws such as the Forest (Conservation) Act, 1980 are inconsistently applied to naturally occurring grasslands, leaving them legally vulnerable and weakly protected.

- Forestry-Centric Climate Policies: Climate and carbon policies prioritise tree cover (REDD+, afforestation drives), often promoting plantations on ecologically unsuitable grasslands, causing biodiversity loss and altered fire regimes.

- Neglect of Disturbance Ecology: Suppression of natural processes like controlled burning and grazing ignores the ecological reality that grasslands depend on disturbance regimes for regeneration and resilience.

- Inadequate Data and Monitoring: There is no comprehensive national inventory or standardised indicators to assess grassland extent, condition, or ecosystem service value, weakening evidence-based policymaking.

- Marginalisation of Pastoral Communities: Traditional pastoral and indigenous management systems are sidelined, despite their proven role in sustainable grazing, fire management, and biodiversity conservation.

- Developmental Bias in Land-Use Decisions: Large-scale diversion for defence, energy, and industrial projects is often justified by branding grasslands as “unused” land, bypassing ecological impact assessments and local consent.

What Measures Can Strengthen Grassland Conservation?

- Correct Ecological Classification: Officially recognise grasslands as distinct natural ecosystems, not degraded forests or wastelands, and classify them as a major land-use category alongside forests and wetlands.

- Explicitly include grasslands in India’s Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) as carbon sinks, focusing on soil carbon, native species, and ecosystem resilience rather than tree plantations.

- Dedicated Legal Protection: Enact a National Grassland Conservation and Grazing Policy, and extend safeguards under existing laws such as the Forest Conservation Act and Wildlife Protection Act to naturally occurring grasslands.

- Adopt Ecosystem-Based Management: Use systems approaches like the Driver-Pressure-State-Impact-Response Framework (DPSIR) to guide land-use decisions, assess cumulative impacts, and align conservation with livelihoods and development needs.

- DPSIR explains environmental change as a cause–effect chain from driving forces and pressures to state changes, impacts, and policy responses. It helps policymakers assess environmental quality and design informed interventions, though applying it is complex due to multiple interacting causes.

- Empower Pastoral and Indigenous Communities: Secure tenure rights over commons, revive customary grazing and fire management practices, and legally recognise community-led stewardship models.

- Science-Driven Restoration: Prioritise restoration of native grass species, regulate invasive plants, and avoid afforestation in ecologically inappropriate grassland landscapes.

- Strengthen Data and Monitoring Systems: Create a national grassland inventory with standardised indicators for biodiversity, carbon storage, fodder capacity, and hydrological services.

- Make environmental impact assessments mandatory for grassland diversion and ensure Gram Sabha consent for the use of common lands.

Conclusion

Grasslands are vital for climate resilience, biodiversity, and livelihoods but remain poorly recognised and protected. Correcting policy blind spots, empowering pastoral communities, and integrating grasslands into climate and legal frameworks is essential. IYRP 2026 provides a crucial window to mainstream grassland conservation.

|

Drishti Mains Question: Grasslands are victims of policy invisibility rather than ecological fragility.Examine the statement in the context of climate governance in India and globally. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why are grasslands often misclassified in policy frameworks?

Grasslands are labelled as wastelands or degraded forests, leading to afforestation, plantations, and diversion despite being natural, biodiversity-rich ecosystems.

2. What is the significance of the International Year of Rangelands and Pastoralists 2026?

It aims to raise awareness, promote responsible investment, secure pastoral land rights, and improve sustainable rangeland management aligned with the SDGs.

3. Why do grasslands fall through global governance gaps?

Climate, biodiversity, and land degradation are handled separately under UNFCCC, CBD, and UNCCD, preventing integrated ecosystem protection.

4. What is the status of grassland protection in India?

Grasslands cover about 24% of India’s area, but less than 1% are under formal protection, with laws like the Forest (Conservation) Act, 1980 applied inconsistently.

UPSC Civil Services Examination, Previous Year Question (PYQ)

Prelims:

Q. In the grasslands, trees do not replace the grasses as a part of an ecological succession because of (2013)

(a) Insects and fungi

(b) Limited sunlight and paucity of nutrients

(c) Water limits and fire

(d) None of the above

Ans: C

Q. The vegetation of savannah consists of grassland with scattered small trees, but extensive areas have no trees. The forest development in such areas is generally kept in check by one or more or a combination of some conditions. Which of the following are such conditions?(2021)

- Burrowing animals and termites

- Fire

- Grazing herbivores

- Seasonal rainfall

- Soil properties

Select the correct answer using the code given below.

(a) 1 and 2

(b) 4 and 5

(c) 2, 3 and 4

(d) 1, 3 and 5

Ans: C

Pax Silica & India’s Inclusion

Why in News?

The United States’ newly appointed Ambassador to India, Sergio Gor, stated that India will be invited to join “Pax Silica,” a US-led coalition aimed at securing and strengthening the critical minerals supply chain.

What is Pax Silica?

- About: It is a US led coalition aimed at building a secure, resilient, and innovation-driven silicon and Artificial Intelligence (AI) supply chain ecosystem through deep cooperation with trusted global partners.

- The inaugural Pax Silica Summit was held in Washington, D.C. in December, 2025.

- Objective: It aims to reduce coercive dependencies on a single country, protect AI-critical materials and enable aligned nations to develop and deploy transformative technologies at scale.

- China dominates the critical minerals supply chain needed for the silicon and AI supply chain ecosystem , refining over 60% of lithium, cobalt, and rare earths. Global diversification efforts are accelerating after China’s restrictions on rare earth magnets disrupted supply chains.

- Participating Nations: Japan, Republic of Korea, Singapore, the Netherlands, United Kingdom, Israel, United Arab Emirates, and Australia.

- Partner countries host key firms such as Sony, Hitachi, Fujitsu, Samsung, SK Hynix, Temasek, DeepMind, MGX, Rio Tinto, and ASML, which power the global AI supply chain.

- Core Commitments: Joint projects to address AI supply chain vulnerabilities across critical minerals, semiconductor design, fabrication and packaging, compute infrastructure, and energy grids, along with protecting sensitive technologies from countries of concern.

Pax Silica and India

- India’s Earlier Exclusion: India currently lacks the critical edge technologies that Pax Silica prioritizes and is not a major repository of critical minerals, which limited its inclusion in the grouping.

- However, just as India joined the US-led Minerals Security Partnership (MSP) (2022), a year after its launch in 2023, becoming its 14th member, India could similarly be inducted into Pax Silica at a later stage.

What are India's Initiatives to Support Silicon and AI Supply Chain?

- India’s Semiconductor Push: Under the USD 10 billion India Semiconductor Mission (ISM, 2021), India aims to build an indigenous semiconductor ecosystem.

- 10 projects approved, involving Rs 1.6 trillion investment, covering fabrication and packaging.

- India’s AI Strategy: Rs 10,372 crore IndiaAI Mission (2024) focuses on indigenous Large Language Models (LLMs) and domestic AI capacity.

- Graphics processing units (GPUs) capacity expanded to 34,333 GPUs, nearly doubling earlier levels.

- Supports a shared cloud-based compute platform for AI training and inference, critical for foundational models tailored to Indian data and context.

- National Critical Mineral Mission (NCMM): It aims to secure India's self-reliance in critical minerals for high-tech, clean energy, and defense.

- The mission covers the full chain—from exploration and mining to processing and recycling—encouraging overseas asset acquisition and international trade ties.

- It will establish mineral parks, promote recycling, and support research, including a Centre of Excellence.

- Minerals Security Partnership (MSP): The MSP, a US initiative, aims to strengthen critical mineral supply chains by ensuring minerals are produced, processed, and recycled to maximize their economic development benefits.

- It directly supports India's mineral self-reliance strategy, complementing domestic actions like the National Critical Minerals Mission and overseas acquisitions by KABIL. It bolsters India’s position in the global race for critical minerals vital for future industries and the energy transition.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is Pax Silica?

Pax Silica is a US-led coalition of nine countries aimed at securing a resilient, innovation-driven semiconductor and AI supply chain.

2. Which countries are part of Pax Silica?

Japan, Republic of Korea, Singapore, Netherlands, UK, Israel, UAE, Australia, and the US.

3. What are India’s key initiatives in semiconductors and AI?

India Semiconductor Mission (ISM), IndiaAI Mission, and National Critical Mineral Mission (NCMM) aim to build indigenous supply chains, AI infrastructure, and critical mineral security.

UPSC Civil Services Examination, Previous Year Questions (PYQs)

Q. Recently, there has been a concern over the short supply of a group of elements called ‘rare earth metals’. Why? (2012)

- China, which is the largest producer of these elements, has imposed some restrictions on their export.

- Other than China, Australia, Canada and Chile, these elements are not found in any country.

- Rare earth metals are essential for the manufacture of various kinds of electronic items and there is a growing demand for these elements.

Which of the statements given above is/are correct?

(a) 1 only

(b) 2 and 3 only

(c) 1 and 3 only

(d) 1, 2 and 3

Ans: (c)

World Hindi Day

The Third Technical Hindi Symposium “Abhyuday-3” was organised with the collaboration of CSIR-National Institute of Science Communication and Policy Research, Indian Institute of Technology Indore, and Indian Institute of Technology Jodhpur to promote Technical Hindi and inclusive science outreach.

- Abhyuday-3 reflected India’s push to expand science and technology outreach through Indian languages, especially Hindi, aligning with World Hindi Day’s goal of strengthening Hindi’s global and functional use.

- World Hindi Day: 10th January is observed annually as World Hindi Day. It was on this day in 1975 that the first World Hindi Conference was held in Nagpur under the auspices of Rashtra Bhasha Prachar Samiti, Wardha (organization founded by Mahatma Gandhi).

- The official observance of World Hindi Day began in 2006, following its announcement by then Prime Minister Dr. Manmohan Singh, distinct from National Hindi Diwas celebrated on 14th September.

- National Hindi Diwas: It commemorates the adoption of Hindi in the Devanagari script as an official language of India by the Constituent Assembly in 1949.

- Hindi Language: Hindi derives its name from the Persian word “Hind”, meaning the land of the Indus River, a term used by Turk invaders in the early 11th century to describe the language of the region.

- It is one of India’s official languages, with English as the other, and is also spoken in countries such as Mauritius, Fiji, Suriname, Guyana, Trinidad and Tobago, and Nepal.

- Hindi evolved from Sanskrit to Prakrit and Apabhramsa, with Khari Boli forming its direct foundation. It later incorporated Persian and Arabic influences.

- The modern Devanagari script took shape in the 11th century, giving Hindi its present written structure.

- Hindi is the third most spoken language in the world, after English and Chinese, with around 600 million speakers. UNESCO recognised Hindi as an official language in 1948, and it was first used in the United Nations General Assembly in 1949.

- Constitutional Provisions Related to the Hindi Language:

|

Article |

Provision |

|

Article 343 |

Declares Hindi in Devanagari script as the official language of the Union; allows continued use of English for official purposes. |

|

Article 344 |

Provides for a Language Commission and Parliamentary Committee to review and recommend the progressive use of Hindi. |

|

Article 351 |

Directs the Union to promote the spread and development of Hindi, enriching it from Sanskrit and other Indian languages. |

|

Article 120 |

Permits the use of Hindi or English in Parliament; other languages allowed with permission of the Chair. |

|

Article 210 |

Allows Hindi, or English, or the official State language to be used in State Legislature proceedings. |

| Read more: World Hindi Day |

Nipah Virus

Two suspected Nipah virus infections among healthcare workers in West Bengal have triggered an urgent state and central public health response, highlighting India’s preparedness against high-risk zoonotic diseases.

- Nipah virus (NiV): It is a highly infectious zoonotic virus, first identified in 1998–99 in Kampung Sungai Nipah, Malaysia.

- According to the World Health Organization (WHO), it is transmitted from animals to humans, with fruit bats (Pteropodidae) as the natural reservoir and pigs as intermediate hosts. The virus belongs to the Henipavirus genus of the Paramyxoviridae family.

- It has the potential for human-to-human transmission, making it a serious public health threat that requires rapid surveillance and containment.

- Symptoms and Clinical Features: Nipah infection usually begins with influenza-like symptoms such as fever, muscle pain, sore throat, and respiratory distress.

- In severe cases, it can progress to acute encephalitis, leading to convulsions, disorientation, coma, and even death.

- Importantly, asymptomatic infections are also reported, complicating containment efforts.

- Diagnosis and Testing: NiV is classified as a Biosafety Level-4 (BSL-4) pathogen, requiring testing in high-security laboratories.

- Diagnosis is confirmed using real time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), ELISA, serum neutralisation tests, histopathology, and virus isolation techniques.

- Treatment and Prevention: There is no approved vaccine for Nipah virus in humans or animals.

- Treatment relies on intensive supportive care and isolation. India, particularly Kerala, has improved outcomes by using monoclonal antibodies and antiviral drugs such as Remdesivir, reducing mortality from 91% in 2018 to around 33% by 2023–25.

- India and Nipah outbreaks: India has witnessed Nipah outbreaks in West Bengal (2007) and Kerala (2018, 2023, and 2025), making early detection, contact tracing, and rapid medical response critical for public health preparedness.

| Read more: Nipah Virus |

Aadhaar Mascot Udai

The Unique Identification Authority of India (UIDAI) has introduced ‘Udai’, a resident-friendly Aadhaar mascot, as a communication tool to make Aadhaar services more accessible and relatable to the public.

- It aims to simplify updates, authentication, offline verification, selective sharing of information, and responsible usage.

Aadhaar

- About: Aadhaar is a 12-digit biometric identification number issued by the UIDAI, serving as a proof of identity and address for residents across India. It is not proof of citizenship or date of birth, and cannot be used to establish nationality.

- Aadhaar is issued by UIDAI, a statutory authority under the Aadhaar Act, 2016.

- Eligibility: Any individual, including foreign nationals, who has resided in India for 182 days or more in the 12 months before the enrolment application date is eligible, subject to submission of one of the 18 notified identity and address documents.

- Utility: Aadhaar facilitates access to direct benefit transfer (DBT), banking services, mobile connections, and various Government and Non-Government services.

- Judicial Stand: In the Justice KS Puttaswamy vs Union of India case 2017, the Supreme Court upheld Aadhaar’s constitutional validity and clarified that, under Section 9 of the Aadhaar Act, 2016, the Aadhaar number itself does not confer or prove citizenship or domicile.

| Read More: Aadhaar is Not a Proof of Citizenship |

Rising FTA Trade Deficit

A NITI Aayog Trade Watch Quarterly report notes that India’s trade deficit with free trade agreement (FTA) partner countries has widened sharply, even as the country recorded strong export growth in electronics and other sunrise sectors.

Key Findings from the NITI Aayog Report

- Sharp Deficit Increase: India's trade deficit with FTA partners widened by 59.2% in Q1 FY26 (April and June). Exports fell 9% to USD 38.7 billion, while imports rose 10% to USD 65.3 billion.

- Structural Export Shift: Electronics emerged as a top performer, growing 47% year-on-year (YoY), now constituting over 11% of total exports. This contrasts with a sharp decline in petroleum exports.

- ASEAN as Key Driver of Deficit: The overall deficit was driven by a 16.9% contraction in exports to ASEAN, India's largest FTA export market. Major declines were seen in Malaysia (-39.7%) and Singapore (-13.2%).

- Import Surge & Diversification: Imports from the UAE surged 28.7%, propelled by new imports of gold compounds and increased petroleum. Imports from China grew 16.3%, led by electronic components.

- Geopolitical & Negotiation Context: The data is critical as India actively negotiates FTAs (e.g., EU, US) and has recently concluded pacts with Oman, New Zealand, and the UK (2025). It also follows a missed 2025 deadline to re-negotiate the ASEAN FTA.

India’s Foreign Trade Pattern

- India’s Export Growth: India’s total exports reached USD 778.21 billion in 2023–24 (Merchandise exports: USD 437.10 billion and service exports USD 341.11 billion).

- Regional Distribution: North America emerged as the largest export destination, followed by strong growth in the EU, West Asia, and ASEAN.

- Largest Export Destinations: United States, United Arab Emirates (UAE), China, Netherlands etc.

- Largest Import Sources: China, Russia, United Arab Emirates (UAE), United States etc.

| Read More: India's Strategic Turn to Free Trade Agreements |