Towards a Resilient Indian Himalayan Region

This editorial is based on “A dangerous march towards a Himalayan ecocide” which was published in The Hindu on 23/01/2026. The article highlights how unsafe land use, infrastructure overreach and ecological disregard are turning climate stress into recurring disasters in Himalayas .The article argues for prioritising disaster resilience and science-based planning over disaster-prone projects in one of India’s most fragile and vital ecosystems.

For Prelims: Indian Himalayan Region ,BRO,EIA,Nature-Based Solutions , Black Carbon, National Mission on Sustaining Himalayan Ecosystem

For Mains: Significance of Himalayan ecosystem, Key issues in Indian Himalayan Region.

The Himalayas, one of the world’s most climate-sensitive mountain systems, are warming nearly 50% faster than the global average, transforming rare disasters into recurring events. In 2025 alone, over 4,000 lives were lost to climate-linked extremes in India , with Himalayan States bearing a disproportionate burden. What appears as a natural calamity is increasingly a man-made risk, driven by unsafe land use and infrastructure excess in fragile terrain. The Himalayan crisis today is not merely environmental, but a decisive test of India’s development wisdom and disaster resilience.

What is the Significance of Himalayan Ecosystem for India?

- Hydrological Security as the "Water Tower of Asia": The Himalayas function as a critical "Third Pole," storing vast freshwater reserves that feed the perennial river systems (Indus, Ganga, Brahmaputra), sustaining India’s agrarian core.

- This cryospheric reserve releases meltwater during the dry pre-monsoon months, acting as a crucial buffer against drought for the Northern Plains “food bowl.”

- For instance, The Hindu Kush Himalayas (HKH) supports about 240 million mountain residents and nearly 1.65–1.9 billion downstream beneficiaries including India.

- Climatological Thermostat & Monsoonal Engine: This mountain chain acts as a massive climatic barrier, preventing frigid Central Asian katabatic winds from turning North India into a cold desert while simultaneously trapping the moisture-laden Southwest Monsoon winds.

- This "orographic lift" is the primary driver of precipitation for the subcontinent, regulating the wet-dry cycles essential for the Kharif crop cycle.

- The range ensures the Gangetic plains receive 1000+ mm of annual rainfall.

- Strategic "Geopolitical Rampart" & Border Defence: The Himalayas provide a natural high-altitude fortress along the Line of Actual Control (LAC).

- The region is now the focal point of India's "Dual-Use Infrastructure" strategy, balancing troop mobility with civilian connectivity to prevent depopulation of border areas.

- For instance, the Sela Tunnel, operationalized in 2024, ensures all-weather access to Tawang. Also the Vibrant Villages Program has allocated ₹4,800 crore to develop 663 border villages to secure this "living wall."

- This counters the 628 "Xiaokang" defense villages China has constructed along the LAC.

- Green Energy Powerhouse: The Himalayas sit at the heart of India’s renewable energy transition.

- Its steep altitudinal gradients generate high kinetic energy ideal for run-of-the-river projects that can stabilize grid intermittency from solar and wind.

- The region has an estimated hydropower potential of 115,550 MW, of which about 46,850 MW (≈40%) is already installed, making the region the country’s largest hydropower reservoir.

- Biodiversity Reservoir & Pharmacological Goldmine: As one of just four global "Biodiversity Hotspots" in India, the Himalayas serve as a genetic vault for endangered flora and potential pharmaceutical breakthroughs (Ayush).

- This biological richness provides essential ecosystem services like pollination and soil stability.

- For instance, out of the roughly 10,000 vascular plant species in the Himalayan Biodiversity Hotspot, approximately 3,160 species (representing 71 genera) are endemic, meaning they are found nowhere else on Earth.

- Cryospheric Sentinel for Global Warming: The health of Himalayan glaciers serves as the most visible "Climate Dashboard" for India, providing early warnings of planetary tipping points that impact sea-level rise and coastal security thousands of kilometers away.

- The rate of glacial retreat here directly correlates to the future submergence risks of coastal metros like Mumbai and Kolkata due to thermal expansion and meltwater.

- Socio-Economic Corridor & Sustainable Tourism: The region supports a unique "High-Altitude Economy" driven by spiritual tourism and horticulture.

- Sustainable management here is critical to prevent "demographic drainage" where locals migrate out due to disaster risks, leaving strategic border zones uninhabited.

- The Char Dham Pariyojana is an ongoing highway project designed to provide all-weather connectivity to the four shrines namely Kedarnath, Badrinath, Yamunotri, and Gangotri.

What Measures has India taken to Promote Sustainability in the Indian Himalayan Region?

- Eco-Mobility Shift- "Parvat Mala" (National Ropeways Programme): The government is aggressively replacing land-scarring road widening with aerial ropeways to minimize slope destabilization and tectonic triggering.

- It has a target of 1,200 km of ropeways across 250+ projects (Budget 2024-25 )

- For instance, Sonprayag-Kedarnath Ropeway cut travel time from 8 hours to 36 minutes, reducing human pressure on trekking routes.

- This "zero-footprint" mobility model bypasses fragile terrain entirely, offering a high-density transport alternative that significantly lowers landslide risks compared to traditional four-lane highways.

- It has a target of 1,200 km of ropeways across 250+ projects (Budget 2024-25 )

- Community-Led Conservation "SECURE Himalaya" Project: Moving beyond fencing-off forests, this initiative integrates snow leopard conservation with sustainable livelihoods to reduce human-wildlife conflict.

- It covered major landscapes (e.g., Gangotri-Govind, Kanchenjunga) and trained 1,000+ local youth in nature guiding and surveillance.

- By treating local communities as the "first line of defense," it monetizes conservation through eco-tourism and medicinal plant value chains, ensuring that protecting biodiversity becomes economically viable for high-altitude dwellers.

- Judicial "Carrying Capacity" Mandate & Legal Rights: A landmark shift in governance has occurred with the Supreme Court legally recognizing the "Right to be Free from Adverse Climate Effects" as a fundamental right (M.K. Ranjitsinh vs Union of India ).

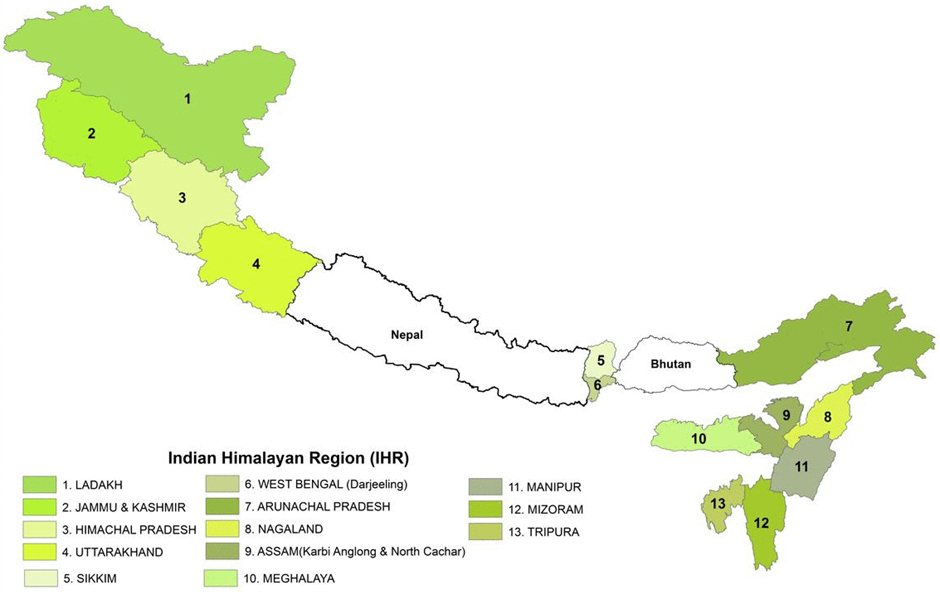

- This has forced the executive to halt the "unlimited growth" model. The Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change has proposed measures to accurately assess the carrying capacity of the 13 Himalayan states.

- In Ashok Kumar Raghav vs Union of India, the Supreme Court also called to address the uncontrolled development in the Indian Himalayan Region (IHR) by pushing for action plans based on "carrying capacity".

- This has forced the executive to halt the "unlimited growth" model. The Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change has proposed measures to accurately assess the carrying capacity of the 13 Himalayan states.

- Decentralized Energy Transition-"PM Surya Ghar" in Hills: To reduce reliance on grid transmission lines (which require deforestation) and diesel generators in remote areas, the government is pushing decentralized rooftop solar micro-grids.

- The government has issued guidelines that offer an additional 10% subsidy per kW for "Special Category States" which include the North-Eastern states and hilly regions like Uttarakhand, Himachal Pradesh, Jammu & Kashmir, and Ladakh.

- This enhances energy security during disasters when main grids fail and reduces the "Black Carbon" emissions from diesel that accelerate glacial melting.

- Hydrological Revival- "Springshed Management" Framework: Recognizing that glaciers are retreating but "springs" (dharas) are the immediate lifeline, NITI Aayog has shifted focus to aquifer recharge over dams.

- This "Dhara Vikas" approach maps underground aquifers to revive drying springs, ensuring water security for hill agriculture without altering natural river flows.

- According to a 2018 report by NITI Aayog, nearly 50% of springs in the IHR are either drying up or have already dried up.

- For instance, project has successfully rejuvenated over 50 lakes and dozens of springs, in Sikkim positioning it as a national model

- "Security Through Sustainability"- Vibrant Villages Programme (VVP): Moving beyond traditional military fortification, this program treats border security as an ecological and demographic challenge.

- The strategy is to reverse "out-migration" from sensitive border zones by creating "climate-smart" livelihoods (eco-tourism, organic clusters), ensuring that border villages remain populated and act as strategic "eyes and ears" without necessitating heavy, ecologically damaging military infrastructure.

- For instance, Kibithoo (Arunachal) transformed into a "smart village" pilot.

- The strategy is to reverse "out-migration" from sensitive border zones by creating "climate-smart" livelihoods (eco-tourism, organic clusters), ensuring that border villages remain populated and act as strategic "eyes and ears" without necessitating heavy, ecologically damaging military infrastructure.

- Circular Economy Pilot- "Deposit Refund Scheme" (DRS) & EPR: To combat the plastic crisis choking Himalayan headwaters, states like Himachal Pradesh are piloting a "buy-back" model.

- This policy forces producers to pay for waste retrieval and incentivizes locals to collect non-biodegradable packaging, effectively putting a "price tag" on litter to create a self-sustaining waste collection economy in difficult terrain.

- The Himachal Pradesh cabinet has launched 'Deposit Refund Scheme 2025', offering cash refunds for returned non-biodegradable packaging to tackle waste.

- Tech-Integrated Resilience- "Glacial Lake Early Warning Systems" (GLEWS): In response to the escalating threat of Glacial Lake Outburst Floods (GLOFs), the NDMA has shifted from reactive relief to proactive, automated surveillance.

- This involves installing Over-the-Horizon (OTH) radars and satellite-linked sensors at high-risk glacial lakes to provide a critical "lead time" (pre-warning) for downstream evacuations, integrating space tech with last-mile community radio connectivity.

- Under the National GLOF Risk Mitigation Programme , early warning systems have been operationalised at South Lhonak Lake (Sikkim) and Shako Cho (Sikkim), combining lake-level sensors, remote sensing and community-based alert dissemination to reduce loss of life from sudden outburst floods.

- Scientific Capacity & "Knowledge-Policy" Bridge (NMSHE Phase-II): The National Mission on Sustaining Himalayan Ecosystem has pivoted from passive observation to active "evidence-based policymaking".

- This institutional mechanism now forces Himalayan states to align their State Action Plans on Climate Change (SAPCC) with rigorous district-level vulnerability maps, replacing ad-hoc decisions with long-term "climate-risk informed" governance.

- Under Phase-II (2021-2026) NMSHE mobilized key Thematic Task Forces (e.g., Himalayan Agriculture, Forest Resources & Plant Diversity etc) and IIT Roorkee's new Centre of Excellence now provides real-time disaster risk data directly to state disaster management authorities.

What Challenges are Associated with the Indian Himalayan Region?

- Cryosphere Collapse and Hydrological Destabilization: The "Third Pole" is witnessing an irreversible cryosphere retreat where rising temperatures are not just melting glaciers but altering precipitation phases (snow to rain), destabilizing the hydrological reliability for downstream agriculture and energy.

- This shift creates a "wet-drought" paradox where intense localized flooding followed by prolonged water scarcity, threatening India's water tower status.

- For instance, 65% faster ice mass loss was recorded in Hindu Kush Himalayas (as per ICIMOD 2024).

- Further, South Lhonak GLOF (Sikkim, October 2023) released 50 cubic million of water, destroying the Teesta III dam.

- Infrastructure-Induced Slope Instability (The "Sinking" Syndrome): Rapid urbanization and strategic mega-projects (highways, tunnels) ignore shear zones and tectonic fragility, leading to severe land subsidence and slope failures.

- The heavy engineering approach (blasting and vertical cutting) without adequate muck disposal or drainage planning has activated dormant landslides, turning habitable towns into disaster zones.

- For instance, an analysis of the Joshimath subsidence shows that between December 2022 and December 2024, parts of Joshimath sank by more than 30 cm.

- Carrying Capacity Overshoot and "Overtourism" Stress: Unregulated religious and adventure tourism has breached the ecological carrying capacity, creating a severe resource-waste imbalance in high-altitude zones.

- The "pump-and-dump" tourism model depletes local springs for luxury consumption while leaving behind non-biodegradable waste that leaches microplastics into headwaters, poisoning the ecosystem at the source.

- For instance, the physical carrying capacity of Kedarnath is around 24,500 visitors per day, but its real carrying capacity is 9,833.

- NITI Aayog and World Bank estimates show that the Indian Himalayan Region now generates 5–8 million metric tonnes of waste annually. Moreover most of these waste are non recyclable.

- Black Carbon and Albedo Feedback Loops: Regional pollution from biomass burning and vehicular emissions deposits Black Carbon on glaciers, darkening the surface and reducing albedo (reflectivity).

- This accelerates melting even in sub-zero temperatures, creating a dangerous feedback loop where "dirty snow" absorbs more heat, amplifying local warming rates beyond the global average.

- A new study (by Climate Trends titled “Impact of Black Carbon on Himalayan Glaciers) suggested that the increase in black carbon emissions has accelerated the melting process in the Himalayas by 4°C over the past two decades, with high concentrations seen in Eastern and Central Himalayas.

- Biodiversity Homogenization and Habitat Fragmentation: Linear infrastructure (railways, transmission lines) is severing wildlife corridors, forcing animals into human settlements and leading to genetic isolation of species like the Snow Leopard.

- Simultaneously, warming allows invasive species to climb to higher altitudes, outcompeting native alpine flora and homogenizing the unique biodiversity of the region.

- A 2024 study by the Indian Institute of Remote Sensing (IIRS) recorded an 11% decline in natural forest cover between 1991 and 2023 in the rapidly urbanising Western Himalaya regions. This loss is primarily driven by an 184% increase in urbanization and infrastructure development.

- Further, Projects like railways and power lines have led to a 71.5% fall in the number of large forest patches across India, significantly increasing "edge-to-interior" ratios and causing habitat fragmentation, especially in Himalayan region.

- Institutional Fragmentation and Policy Dilution: Himalayan governance remains siloed, with roads, hydropower and tourism handled by separate ministries in the absence of a unified, Himalayan-specific building code or integrated ecological oversight.

- The dilution of EIAs for “strategic” projects has weakened legal safeguards, enabling ecologically irreversible interventions.

- Under the Forest (Conservation) Amendment Act, 2023, projects within 100 km of the LAC/International Border are exempt from forest clearance, allowing strategic projects to bypass full EIAs in sensitive landscapes such as Changthang (Ladakh).

- The "Seismic Gap" and Reservoir-Induced Risks: The Central Himalayas lie over an active seismic gap where accumulated tectonic stress is increasingly compounded by the immense water load of mega-dams, heightening the risk of reservoir-induced seismicity.

- Placing rigid concrete structures over active shear zones without adequate seismic buffers turns future earthquakes into cascading failures rather than isolated tremors.

- The NGRI (2025) flags the region as overdue for a nearly M8.5 earthquake, while over 1,500 micro-tremors recorded near the Tehri Dam indicate rising stress on local fault lines.

- Placing rigid concrete structures over active shear zones without adequate seismic buffers turns future earthquakes into cascading failures rather than isolated tremors.

- "Winter Fire" Regimes and Carbon Sink Reversal: A catastrophic ecological inversion is occurring where traditional summer fires now rage in winter due to "snow droughts" and dry biomass accumulation, effectively turning the Himalayan carbon sink into a net emitter.

- This thermal anomaly incinerates dormant seed banks and facilitates the aggressive invasion of flammable chir-pine into moisture-retaining oak forests, permanently desiccating the soil and destroying the mountain's natural water-sponge capability.

- Uttarakhand and the Central Himalayan region are witnessing an abnormally dry winter, with negligible rainfall and snowfall leading to crop losses, hydrological stress, and risks of negative glacier mass balance.

- The severity of this climate anomaly is evident from forest fires reported even in high-altitude protected areas such as the Nanda Devi National Park.

- In Uttarakhand Himalayas between 14th January and 20th January, 2026, there were 440 forest fires compared to 45 in the same period in 2025, nearly a ten-fold increase.

What Measures are Needed for Sustainable Management of Indian Himalayan Region?

- Enforce a Himalayan-Specific Land-Use and Building Code: India needs a legally binding Himalayan Mountain Code that replaces generic plains-based norms with slope-sensitive, geology-aligned standards.

- This code must regulate road width, hill-cut angles, tunnel density, building height, and permissible load in seismic and landslide zones. Development permissions should be conditional on micro-zonation and cumulative impact thresholds.

- Such a code would convert “precaution” from advisory to enforceable law.

- This code must regulate road width, hill-cut angles, tunnel density, building height, and permissible load in seismic and landslide zones. Development permissions should be conditional on micro-zonation and cumulative impact thresholds.

- Shift from Infrastructure-Led Growth to Resilience-Led Planning: Development strategy must pivot from asset creation to risk minimisation, making disaster resilience the primary design parameter.

- Infrastructure should be evaluated not by speed or capacity, but by lifetime stability, maintenance burden and failure consequences.

- This requires embedding geologists, ecologists and disaster scientists at the project design stage rather than post-clearance retrofitting. Resilience-first planning reduces long-term fiscal and human costs.

- Institutionalise Cumulative Impact and Basin-Scale Assessments: Project-wise clearances must give way to landscape and river-basin level planning, especially for hydropower, roads and tourism clusters.

- Basin authorities should cap infrastructure density based on slope stability, sediment load and carrying capacity.

- This prevents the “death by a thousand cuts” effect where individually cleared projects collectively destabilise entire valleys. Integration across sectors is the only way to arrest systemic risk.

- Prioritise Nature-Based Solutions as Core Infrastructure: Forests, wetlands, alpine meadows and riparian buffers should be treated as critical natural infrastructure, not auxiliary conservation assets.

- Slope stabilisation through native afforestation, flood moderation through wetlands and avalanche control through forest belts are often cheaper and more durable than engineering fixes.

- Budgetary allocations must explicitly fund ecosystem restoration as a disaster-risk-reduction strategy. This aligns ecological repair with economic prudence.

- Regulate Tourism Through Carrying Capacity and Spatial Zoning: Tourism policy must move from volume-driven to capacity-regulated and seasonally staggered models.

- Fragile zones should have strict caps on footfall, vehicles and construction, enforced through permits and pricing signals.

- Tourism infrastructure should be decentralised to spread pressure and stabilise local livelihoods. Managed tourism protects both ecosystems and the economic base that depends on them.

- Re-engineer Hydropower and Transport with Context-Sensitive Design:Hydropower and road projects must adopt terrain-adaptive designs, narrower roads, flexible alignments, minimal tunnelling, and distributed energy systems over mega-structures.

- Geological uncertainty should be treated as a design constraint, not an inconvenience.

- Retrofitting unstable projects must be secondary to preventing destabilising designs in the first place. This reduces lock-in of irreversible risk.

- Strengthen Local Institutions and Community Stewardship: Local communities must shift from being project-affected stakeholders to co-managers of landscapes. Empowering panchayats with planning authority, disaster funds and ecological monitoring roles improves compliance and early warning.

- Indigenous knowledge on slope behaviour, water flows and forest management should inform formal decision-making. Decentralised stewardship enhances legitimacy and on-ground effectiveness.

- Integrate Climate, Disaster and Development Governance: Climate adaptation, disaster risk reduction and infrastructure planning should be merged into a single governance framework for the Himalayas. Fragmented mandates dilute accountability and encourage policy evasion.

- Unified planning enables long-term horizon setting, trade-off evaluation and transparent prioritisation. Protecting the Himalayas requires governing them as a connected earth system, not as isolated administrative sectors.

Conclusion:

Protecting the Himalayas is no longer a choice between development and conservation, but a choice between foresight and failure. When fragile mountains are forced to carry plains-based ambitions, disasters become policy-made, not natural. A resilience-led, ecology-first governance framework is the only pathway that secures lives, livelihoods and national security. In the Himalayas, sustainability is not an ideal , it is the last line of defence.

|

Drishti Mains Question “The Himalayan crisis is as much a failure of governance and planning as it is of climate change.” Critically examine this statement in the context of infrastructure development, land-use practices and disaster resilience in the Indian Himalayan Region. |

FAQs

1. Why are disasters increasing in the Himalayas?

Because unsafe land use and infrastructure overreach are amplifying climate-driven extremes in fragile terrain.

2. Is climate change the sole cause of Himalayan disasters?

No. Climate change acts as a risk multiplier; poor planning and ecological disruption are the primary triggers.

3. Why are plains-based development models unsuitable for the Himalayas?

They ignore slope stability, seismicity and carrying capacity, turning development into a source of risk.

4. What is the core policy gap in Himalayan governance?

The absence of a unified, Himalayan-specific land-use and building code and integrated oversight.

5. What is the most effective way forward?

Shift from infrastructure-led growth to resilience-led, ecology-first planning anchored in local governance.

UPSC Civil Services Examination, Previous Year Questions (PYQs)

Prelims:

Q. Consider the following pairs: (2020)

- Peak Mountains

- Namcha Barwa Garhwal Himalaya

- Nanda Devi Kumaon Himalaya

- Nokrek Sikkim Himalaya

Which of the pairs given above is/are correctly matched?

(a) 1 and 2

(b) 2 only

(c) 1 and 3

(d) 3 only

Ans: (b)

Q. If you travel through the Himalayas, you are likely to see which of the following plants are naturally growing there? (2014)

- Oak

- Rhododendron

- Sandalwood

Select the correct answer using the code given below:

(a) 1 and 2 only

(b) 3 only

(c) 1 and 3 only

(d) 1, 2 and 3

Ans: (a)

Q. When you travel in Himalayas, you will see the following: (2012)

- Deep gorges

- U-turn river courses

- Parallel mountain ranges

- Steep gradients causing landsliding

Which of the above can be said to be the evidence for Himalayas being young fold mountains?

(a) 1 and 2 only

(b) 1, 2 and 4 only

(c) 3 and 4 only

(d) 1, 2, 3 and 4

Ans: (d)

Mains:

Q1. Differentiate the causes of landslides in the Himalayan region and Western Ghats. (2021)

Q2. How will the melting of Himalayan glaciers have a far-reaching impact on the water resources of India? (2020)

Q3. “The Himalayas are highly prone to landslides.” Discuss the causes and suggest suitable measures of mitigation. (2016)