India’s Roadmap to Transform Maoist-Affected Areas | 13 Dec 2025

This editorial is based on "Message to Maoists, from one of their own: Violence doesn’t work” which was published in The Indian Express on 05/12/2025. The article shows the limitation of a violence based movement to achieve social justice and inclusive development. Further it shows the multifaceted approach of the government to eliminate the Red Terror.

For Prelims: Forest Rights Act Left Wing Extremism PMGSY Operation Black Forest Operation Greyhound Samadhan Framework

For Mains: History of the Naxal Movement in India, Key Approaches Taken By The Government To Eradicate The Naxal Menace.

In recent years, the armed insurgency has witnessed a dramatic erosion of strength and influence. What once spanned over 200-plus districts across the so-called “Red Corridor” has now shrunk to 11 districts largely confined to small pockets in central India (Red Pocket). Compared to the period of 2004-14, the period of 2014–24 saw a 73% reduction in security personnel deaths and a 74% reduction in civilian deaths. In 2024, the highest number of Naxalites (290) were neutralized in a single year. These trends clearly illustrate a significant erosion of the Naxal movement itself, marked by dwindling cadre strength, shrinking territorial presence, and weakening ideological mobilisation

What is the History of the Naxal Movement in India?

- Origins and Ideological Roots

- Birth of the Movement (1967): Naxalism, officially termed Left-Wing Extremism (LWE), originated from the peasant uprising in Naxalbari village, West Bengal, led by Charu Majumdar, Kanu Sanyal, and Jangal Santhal.

- Ideological Foundation: The movement drew inspiration from Mao Zedong’s doctrine of a prolonged “people’s war,” advocating armed struggle against the state.

- Socio-Economic Context

- Deep Structural Inequalities: Early Naxalism emerged from severe socio-economic distortions such as unequal land ownership, bonded labour, caste oppression, forest-land dispossession, and chronic political marginalization of tribal communities.

- Failure of Land Reforms: Inadequate implementation of land reforms in the 1950s–60s further aggravated rural distress.

- Neglect of Tribal Regions: The state’s limited presence in remote tribal districts created a vacuum, enabling radical groups to mobilize discontent.

- Armed Revolt as a Perceived Solution: For the poorest cultivators and landless labourers, armed resistance came to be viewed as the only path to justice.

- Early Expansion and Escalation (1970s–1980s)

- Peak Violence in 1971: Independent India witnessed a high point with 3,620 violent incidents linked to Naxalism.

- Spread Across States: During the 1980s, the People’s War Group expanded operations into Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Chhattisgarh, Uttar Pradesh, Jharkhand, Bihar, and Kerala.

- Consolidation of LWE Groups

- Mergers and Unification: After the 1980s, various Left-wing extremist groups began merging.

- Formation of CPI (Maoist) in 2004: The unification of major factions led to the creation of the CPI (Maoist), intensifying violence and organizational strength.

What Strategies Has India Implemented to Address Maoist Insurgency?

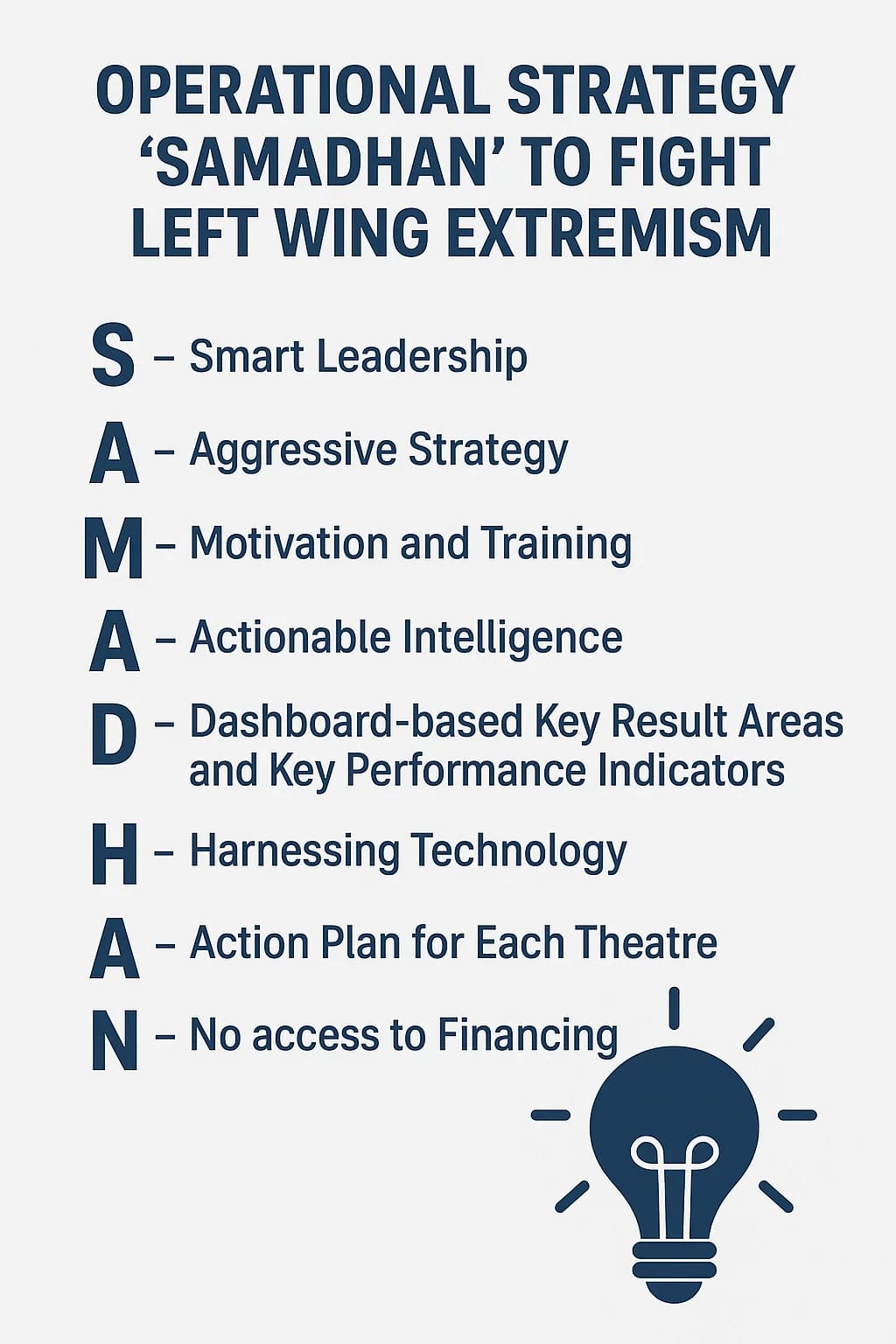

- SAMADHAN Framework: It is MHA’s integrated, multi-dimensional strategy to counter Left Wing Extremism through coordinated security action, technology, leadership, and development. It combines policing reforms with targeted operations and denial of Maoist finances.

- Surrender and Rehabilitation Policy: Offers Naxal/Maoist cadres a dignified exit: if they lay down arms they receive financial aid, vocational-training, monthly stipend or lump sum grants, and social reintegration support.

- In 2025 alone, official police data shows over 1,040 cadres have surrendered so far.

- Security Measures

- Operation Steeplechase: In the early 1970’s during the President's rule, Operation Steeplechase, a joint Army-CRPF-Police operation, was launched against the Naxalites in the bordering districts of West Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa, which were worst affected.

- Salwa Judum Movement: The Salwa Judum movement was the counter-Naxal operation that ran from 2004 to 2009.

- Under this, a force of volunteers was trained by the security forces for the defence of villages in Naxal-affected areas and to offer an alternative to the youths who were being compelled by the CPI-Maoist cadres to join them.

- Operation Green Hunt: It was launched in 2009 against insurgents in Chhattisgarh, the epicentre of violence between Maoist fighters and security forces. The Operation dealt a severe blow to the Naxal insurgency and practically cleansed Andhra Pradesh of CPI-Maoist footprints.

- Operation Octopus(2022): Targeted CRPF-led operation focused on Burha Pahar / Garhwa / other corridor strongholds to clear heavily mined Naxal pockets.

- Operation Double Bull: Intensive multi-day CRPF operations targeted at disrupting Naxal funding/logistics. Numerous caches seized, arrests made leading to reduction in local Naxal activity.

- Operation Black Forest (April 2025): A decisive campaign on the Chhattisgarh–Telangana border (Kareguttalu/Kurraguttalu hills / Abujhmad fringe) that “cleared” key terrain and targeted top Maoist commanders.

- Infrastructure & Connectivity: Between 2014 and 2024, 12,000 kilometers of roads have been constructed in Left-Wing Extremism–affected states, budgets have been approved for 17,500 roads, and 5,000 mobile towers have been installed at a cost of ₹6,300 crore.

- The government’s infrastructure initiatives in Left-Wing Extremism (LWE)-affected areas include road, rail, and telecom projects to improve connectivity and administration.

- Key schemes are the Road Connectivity Project for LWE Areas (RCP–LWE), Pradhan Mantri Gram Sadak Yojana (PMGSY) with LWE focus, and LWE Special Infrastructure Scheme (LWE-SIS), along with special rail projects in Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, and Odisha.

- Additionally, telecom expansion through BharatNet (Optical Fibre to Gram Panchayats) and LWE mobile towers ensures high-speed broadband and communication in remote tribal regions.

- The government’s infrastructure initiatives in Left-Wing Extremism (LWE)-affected areas include road, rail, and telecom projects to improve connectivity and administration.

- Governance Measures: Panchayat Extension To Scheduled Areas Act (PESA) and Forest Rights Act 2006: PESA strengthens tribal self-governance through empowered Gram Sabhas, while FRA secures land and forest rights, including control over Minor Forest Produce. Together, they enhance tribal autonomy and reduce vulnerability to Naxal influence.

What Factors Continue to Make India Vulnerable to Maoist Insurgency?

- Tactical Asymmetry and "Contactless" Warfare: The insurgency has shifted from direct guerilla confrontations to "invisible enemy" tactics, heavily relying on Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs) and potential drone usage to negate the numerical superiority of security forces (SFs).

- This asymmetrical warfare allows a shrinking cadre to inflict disproportionate psychological and physical damage while avoiding direct engagements.

- In January 2025, an IED explosion in Bijapur resulted in the death of 8 security personnel, highlighting the continuing threat of Left-Wing Extremism in central India.

- Governance Deficit in Tribal Land Rights (FRA & PESA): Vulnerability stems from the "trust deficit" created by the poor implementation of the Forest Rights Act (FRA) and PESA, where rejection of land claims and delays in community rights recognition feed the Maoist narrative of "state exploitation."

- The perception that the state prioritizes corporate mining over tribal welfare remains a potent recruitment tool for the rebels.

- For instance, over 38% of all claims over land made under the Forest Rights Act (FRA), 2006 till November 2022, have been rejected.

- Recent protests in the Hasdeo Arand region highlight continuing tribal anxiety over displacement and resource extraction.

- Historical Socio-Economic Deprivation: Chronic poverty and social exclusion in tribal belts create fertile ground for insurgent mobilisation.

- For instance, over 40–50% households in core LWE districts fall under deprivation indicators.

- Backward districts like Sukma, Malkangiri and Gadchiroli rank among India’s poorest, sustaining resentment against the state.

- Persisting poverty and exclusion can lead to dilution of gains made .

- Difficult Terrain and Inadequate State Penetration: Dense forests, hilly terrain and porous state borders create natural safe havens and facilitate mobility.

- For example the Dandakaranya region spanning Chhattisgarh–Maharashtra–Odisha remains a key guerrilla base due to its difficult terrain.

- Inter-State Coordination Challenges: LWE areas straddle multiple states, complicating intelligence sharing and joint operations.

- For instance, The 2013 Darbha Valley attack exploited gaps between Odisha–Chhattisgarh coordination.

- Youth Unemployment and Lack of Livelihood Options: Limited non-farm opportunities and skill training may push youth towards re-recruitment.

- As per NITI Aayog, Core LWE districts have higher than national average youth unemployment .

How Can India Transform Maoist-Affected Areas into Thriving Development Hubs?

- Hyper-Localized "Smart" Governance via PESA Integration: To bridge the trust deficit, the state must move beyond symbolic representation to active "Digital Sovereignty" for tribal bodies by empowering Gram Sabhas under PESA with real-time digital dashboards for fund utilization.

- Implementing a "Bottom-Up" planning model allows local communities to veto or approve development projects, ensuring that infrastructure aligns with tribal ecological values rather than perceived corporate greed.

- This digital democratization transforms the narrative from "state imposition" to "participatory development," effectively neutralizing the Maoist propaganda of state exploitation.

- "Forest-to-Market" Value Chain Sovereignty: Economic transformation requires shifting from raw material extraction to local value addition by establishing a dense network of Van Dhan Vikas Kendras (VDVKs) equipped with processing technology for Minor Forest Produce (MFP).

- By creating a "Tribal-Start-up Ecosystem" that brands and exports products like Mahua and wild honey directly to global markets, the state can ensure wealth retention within the community.

- This "Bio-Economy" approach dismantles the exploitative middleman structure that insurgents often leverage for levies, replacing it with sustainable, community-owned wealth generation.

- Transparent and Participatory Mining & Resource Management: Introduce fair compensation, R&R and share of mineral royalties to local communities through the DMF (District Mineral Foundation)

- Also Encourage community-led monitoring to prevent displacement grievances exploited by Maoists.

- Encouraging Private Investment and Public–Private Partnerships: Offer risk guarantees, tax incentives, and infrastructure support to attract industries in agro-processing, textiles, food parks, and renewable energy.

- For instance, Dantewada’s Steel Slurry Pipeline and NMDC-based industrial corridor catalysed local jobs and services.

- Leveraging Technology for Governance and Development: Use GIS mapping, drones, and e-governance platforms for service delivery and monitoring.

- Expand digital payments and DBT to eliminate leakages, building trust in state institutions.

- Reconciliation, Trust-Building, and Reintegration: Strengthen surrender and rehabilitation policies by promoting uniform policies across states with assured livelihoods, housing, and skill training.

- Over 1,600 Maoists surrendered in Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand (2018–2023) due to improved welfare incentives.

Conclusion:

Accelerated settlement of land and forest rights, credible grievance redress, and strict enforcement of welfare entitlements are vital to rebuilding state legitimacy. Strengthening PRIs, empowering Gram Sabhas, and widening access to justice through legal-aid clinics can deepen democratic participation. Ultimately, durable peace will rest on a participatory, tribal-sensitive governance framework that addresses structural inequities while preventing the re-emergence of insurgent influence.

|

Drishti Mains Question: “Economic marginalization and resource alienation created the original social base for Naxalism, but development interventions must go beyond physical infrastructure to achieve sustainable peace.” Discuss |

FAQs:

Q. Why is a rights-based development approach essential in post-LWE regions?

A rights-based approach addresses long-standing structural grievances—land alienation, exclusion from forest rights, and weak public services. By ensuring legal entitlements and accountable governance, it builds state legitimacy and prevents relapse into conflict.

Q. How do strengthened PRIs contribute to long-term peace in former Naxal areas?

Empowered PRIs deepen democratic participation, improve local planning, and enhance oversight of development schemes. In tribal belts, functional Gram Sabhas ensure culturally sensitive decision-making, reducing the political vacuum exploited by extremists.

Q. Why is grievance redress critical after security operations?

Clearance operations remove the immediate threat but unresolved grievances—land disputes, compensation delays, or service delivery failures—can fuel renewed alienation. Responsive mechanisms restore trust and enhance administrative credibility.

Q. What role do livelihoods play in consolidating gains against LWE?

Sustainable livelihoods reduce economic vulnerability and dependency on insurgent networks. Strengthening agriculture, MFP value chains, skill programmes, and market linkages stabilises incomes and anchors communities to state systems.

Q. Why is justice access a priority in LWE-affected districts?

For decades, insurgents filled the vacuum of quick dispute settlement. Expanding legal-aid clinics, mobile courts, and grievance camps ensures timely justice, restores faith in constitutional institutions, and reinforces rule-of-law based governance.

UPSC Civil Services Examination, Prelims Practice Question

Mains

Q. Naxalism is a social, economic and developmental issue manifesting as a violent internal security threat. In this context, discuss the emerging issues and suggest a multilayered strategy to tackle the menace of Naxalism ( 2022).

Q. What are the determinants of left-wing extremism in Eastern India? What strategy should the Government of India, civil administration, and security forces adopt to counter the threat in affected areas? ( 2020).

Q. Left Wing Extremism (LWE) is showing a downward trend, but still affects many parts of the country. Briefly explain the Government of India’s approach to counter the challenges posed by LWE. ( 2018)

Q. The government’s development drives for large industries in backward areas have isolated tribal populations facing multiple displacements. With Malkangiri and Naxalbari as case studies, discuss corrective strategies needed to reintegrate affected citizens into mainstream social and economic growth. ( 2015)