India–EU FTA and Strategic Realignment | 29 Jan 2026

This editorial is based on “India-EU ties: Stagnation to strategic realignment” which was published in The Hindustan times on 27/01/2026. The article examines the transformation of India–EU relations from prolonged stagnation to strategic realignment. It highlights how the India–EU FTA and deeper cooperation in trade, technology, security, and sustainability position the partnership as a key pillar of the emerging multipolar order.

For Prelims:CBAM,Carbon Credit Trading Scheme, INDIA-EU FTA,TRIPS,Non Tariff Barriers.

For Mains: India-EU ties over time, Phases of India EU FTA signing, key areas of convergence and divergence between India-EU, Measures needed to strengthen ties.

In a world marked by fractured supply chains, sanctions, politics, and sharpening great-power rivalry, India and the European Union have taken a decisive geopolitical step by signing the India–EU Free Trade Agreement. With bilateral trade at $136 billion, the EU contributing 16% of India’s FDI, and the FTA expected to unlock $75 billion in additional exports, economic integration is now reinforcing strategic alignment. For Europe, the agreement enables diversification away from China and the US and for India, it secures access to the world’s largest single market. Together, the two partners are positioning themselves as anchors of stability in an emerging multipolar, rules-based global order.

How India-EU Ties have Evolved Over Time?

- Phase I: Normative Engagement (1990s–2004)

- Post–Cold War reorientation led to economic and political engagement driven by trade, development assistance, and shared democratic values, culminating in the Strategic Partnership in 2004.

- Phase II: Institutional Optimism, Limited Convergence (2005–2013)

- The Joint Action Plan (2005) and Broad-based Trade and Investment Agreement (BTIA) talks (2007) expanded dialogue architecture, but progress stalled due to Eurozone crises, regulatory divergence, and lack of political push,revealing a gap between ambition and delivery.

- Phase III: Strategic Drift amid Global Uncertainty (2014–2019)

- Despite growing trade, ties remained under-leveraged as Europe turned inward and India diversified partnerships; the relationship remained economically transactional and geopolitically underdeveloped.

- Phase IV: Strategic Recalibration (2020–2024)

- Covid-19, supply-chain shocks, and China’s assertiveness triggered convergence on resilience, technology, and the Indo-Pacific, leading to revival of trade talks and the Trade and Technology Council (2022).

- Both sides began reassessing the FTA not merely as a commercial instrument but as a tool for resilience, diversification, and strategic autonomy.

- Covid-19, supply-chain shocks, and China’s assertiveness triggered convergence on resilience, technology, and the Indo-Pacific, leading to revival of trade talks and the Trade and Technology Council (2022).

- Phase V: Strategic Consolidation (2025–present)

- The signing of the India–EU FTA, security and defence partnership, and mobility frameworks mark a shift from sectoral cooperation to comprehensive strategic alignment, positioning India and the EU as co-architects of a stable multipolar order.

What are the Key Provisions of the INDIA-EU FTA?

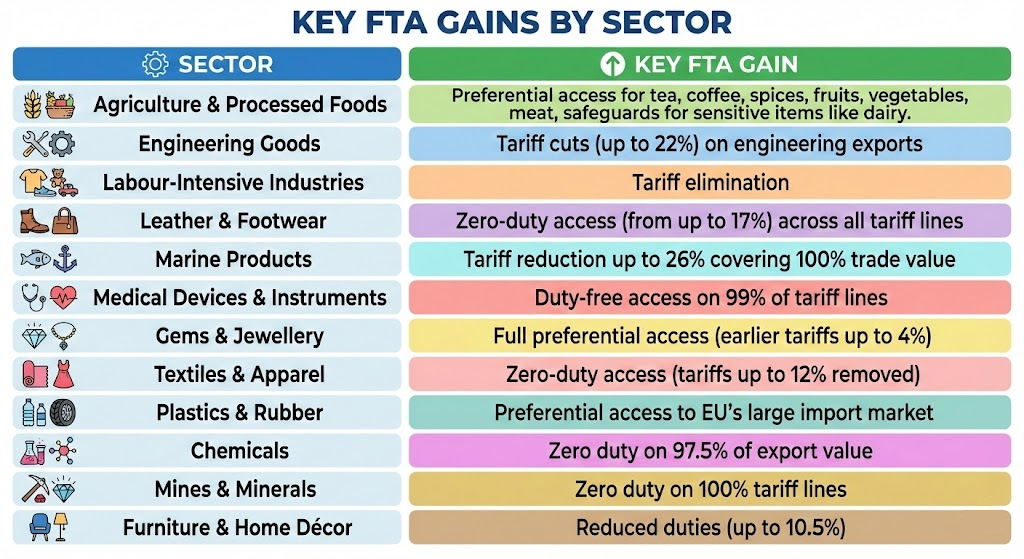

- Unprecedented Tariff Liberalisation in Goods Trade: Preferential access for over 99% of India’s exports (by value) to the EU.

- Immediate zero-duty access for a large share of labour-intensive sectors.

- Phased tariff elimination and calibrated tariff reductions for select sensitive products.

- Use of Tariff Rate Quotas (TRQs) for automobiles, steel, select agri and marine products to balance market access with domestic protection.

- Calibrated Reciprocal Market Access for EU Exports: India offers tariff concessions on 92.1% of tariff lines covering 97.5% of EU exports.

- Gradual tariff elimination over 5–10 years for sensitive industrial goods.

- Controlled liberalisation in agriculture through TRQs for limited fruit categories.

- Facilitates access to high-technology EU inputs, lowering production costs and enhancing competitiveness of Indian industry.

- Product-Specific Rules of Origin (PSRs): Clearly defined origin criteria ensuring substantial processing within India or the EU.

- Alignment with existing global value chains to prevent trade deflection.

- Flexibility for sourcing non-originating inputs, particularly benefiting MSMEs.

- Provision for self-certification (Statement of Origin) to reduce compliance costs.

- Safeguarded Agricultural Liberalisation

- The EU has committed to providing favourable and preferential market access to Indian agricultural and processed food exports.

- This includes key products such as tea, coffee, spices, fresh fruits and vegetables, and processed food items, where India enjoys strong comparative advantage.

- India has adopted a cautious and calibrated approach in agriculture by not granting market access to the EU in sensitive sectors.

- These include dairy, cereals, poultry, soymeal, and certain fruits and vegetables, which are critical for domestic food security, farmer livelihoods, and rural employment.

- The EU has committed to providing favourable and preferential market access to Indian agricultural and processed food exports.

- Services Trade: High-Value Commitments

- The EU has undertaken commercially meaningful and predictable commitments in the services sector by opening 144 services sub sectors to Indian service suppliers.

- These include key areas such as IT and IT-enabled services, professional services, other business services, and education services. The EU has also assured non-discriminatory treatment and regulatory certainty.

- India has committed to opening 102 services subsectors to EU service providers under the FTA.

- These commitments aim to facilitate the entry of high-technology services, investment, and global best practices from the EU into the Indian economy.

- The EU has undertaken commercially meaningful and predictable commitments in the services sector by opening 144 services sub sectors to Indian service suppliers.

- Mobility & Movement of Professionals

- The EU has agreed to a facilitative and predictable mobility framework covering multiple categories of professionals.

- This includes access for Intra-Corporate Transferees (ICTs) and business visitors, along with commitments in 37 sectors for Contractual Service Suppliers (CSS) and 17 sectors for Independent Professionals (IP).

- Moreover the EU has extended entry and working rights to dependents and family members of ICTs, as well as provisions supporting student mobility and post-study work opportunities.

- Also, in EU member states where regulations do not exist, AYUSH practitioners will be able to provide their services based on professional qualifications earned in India

- This includes access for Intra-Corporate Transferees (ICTs) and business visitors, along with commitments in 37 sectors for Contractual Service Suppliers (CSS) and 17 sectors for Independent Professionals (IP).

- The FTA establishes a predictable and facilitative framework for business mobility, covering short-term, temporary, and business travel in both directions.

- Additionally, India has secured a framework for constructive engagement on Social Security Agreements over a five-year horizon, aimed at reducing the burden of double social security contributions and facilitating smoother professional mobility between the two regions.

- The EU has agreed to a facilitative and predictable mobility framework covering multiple categories of professionals.

- Non-Tariff Barriers & Trade Facilitation

- The EU has committed to reducing non-tariff barriers through enhanced regulatory transparency, simplified customs procedures, and improved Sanitary and Phytosanitary (SPS) measures.

- These steps aim to address procedural and compliance challenges faced by Indian exporters, particularly in agriculture, food, and manufactured goods.

- India has agreed to strengthen cooperation on customs, trade facilitation, SPS, and Technical Barriers to Trade (TBT) disciplines.

- The EU has committed to reducing non-tariff barriers through enhanced regulatory transparency, simplified customs procedures, and improved Sanitary and Phytosanitary (SPS) measures.

- CBAM & Climate-Trade Interface

- Under the FTA, the EU has provided forward-looking assurances related to the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM).

- The agreement provides India with a Most-Favoured-Nation assurance, under which any flexibilities accorded by the EU to third countries under the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism will be applicable to India.

- India has agreed to constructive engagement and dialogue on CBAM-related issues while safeguarding its development priorities.

- Through cooperation rather than coercion, India seeks to align climate action with trade competitiveness, ensuring that environmental standards do not become disguised trade barriers.

- Under the FTA, the EU has provided forward-looking assurances related to the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM).

Note: Under the India–EU FTA, tariffs on car imports into India will gradually reduce from 110% to 10% under an annual quota of 250,000 vehicles, while electric vehicles remain excluded from tariff relief.

- This move is expected to benefit European automakers, which currently hold less than 4% of India’s car market, and may attract fresh investments.

- However, there are concerns that early tariff cuts could hinder the growth of India’s domestic automobile industries before they achieve global competitiveness, potentially affecting local manufacturers and the emerging EV ecosystem.

What are the Other Areas of Convergence in India-EU Relations?

- Strategic Autonomy & Multipolar World Order: India and the EU converge on resisting bloc politics and preserving strategic autonomy amid US–China rivalry.

- Both prefer issue-based coalitions, sovereignty, and flexibility over alliance entanglements.

- This alignment positions them as stabilising middle powers shaping a multipolar order rather than followers of great-power binaries.

- The Joint India-European Union Comprehensive Strategic Agenda reaffirmed commitment to prosperity and sustainability. EU leaders were chief guests at India’s 77th Republic Day, signalling political recalibration.

- Both prefer issue-based coalitions, sovereignty, and flexibility over alliance entanglements.

- Defence, Maritime Security & Indo-Pacific Stability: Security convergence has deepened as both face disruptions to sea lanes, cyber threats, and grey-zone coercion in the Indo-Pacific.

- India brings regional presence and naval capability, while the EU contributes capacity-building and maritime domain awareness. Security cooperation now complements economic engagement.

- The Security and Defence Partnership (SDP) expands cooperation in maritime security, cyber-defence, and counter-terrorism and joint naval exercises.

- Supply Chain Resilience & De-Risking from China: Both India and the EU seek to reduce overdependence on concentrated manufacturing hubs, especially China, without abrupt decoupling.

- India offers scale, demographics, and manufacturing potential, while the EU provides capital, technology, and standards. This convergence is driven by risk management rather than ideology.

- EU leaders have framed India as a trusted partner for diversification. For instance, EU firms account for 16% of total FDI into India with over 6,000 companies operating locally.

- European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen has strongly endorsed the sentiment that a growing India benefits the world. Specifically, during the finalization of a major EU-India trade deal, she stated: "When India succeeds, the world is more stable, more prosperous and more secure, and we all benefit".

- Technology Governance & Trusted Digital Ecosystems: India and the EU converge on the need for democratic governance of technology—balancing innovation with regulation.

- Unlike the US’s market-led approach or China’s state-centric model, both favour rules-based digital ecosystems. Cooperation spans AI, semiconductors, cyber norms, and digital public infrastructure.

- The India–EU Trade and Technology Council (2022) institutionalised cooperation on trusted tech, supply chains, and green technologies; multiple TTC working groups are now operational.

- Multilateralism & Global Governance Reform: India and the EU converge in defending multilateral institutions at a time of fragmentation, sanctions politics, and rule erosion. Both see reformed multilateralism—not unilateralism—as essential for global stability. India’s rise and EU’s normative weight are increasingly complementary.

Data/Example:- India and EU coordinate positions in forums like G20, WTO reform debates, and climate negotiations.

What are the Key Areas of Divergence in India-EU Relations?

- "Green Protectionism"-The CBAM Deadlock: The primary economic friction is the EU's Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), which India views as a discriminatory "green tax" disguised as climate action.

- India argues this unilateral levy penalizes its developing industrial base by ignoring "Common But Differentiated Responsibilities" (CBDR), effectively neutralizing the tariff benefits gained under the new FTA by adding a 20-35% cost layer to exports.

- While the recent India–EU FTA signals progress through an MFN clause on CBAM-related flexibilities, its practical effectiveness in shielding Indian exports remains uncertain.

- Geopolitical Dissonance- The "Russia-Ukraine" Litmus Test: A sharp strategic divide persists over the Russia-Ukraine conflict, where the EU demands alignment on sanctions as a "values-based" prerequisite, while India maintains "Strategic Autonomy."

- The EU views India's purchase of Russian oil as indirectly funding the war against Europe, whereas India frames it as a non-negotiable energy security imperative for its 1.4 billion population, creating a permanent diplomatic irritant.

- India was the third highest buyer of Russian fossil fuels, importing a total of €2.3 billion of Russian hydrocarbons in December 2025 (CREA), while the EU urged tighter sanctions.

- Further, India abstained on key UN resolutions criticizing Russia, diverging from the EU's unified block vote.

- Digital Sovereignty-GDPR vs. DPDP Act Alignment: While the EU considers its General Data Protection Regulation the "gold standard" for data adequacy, India’s Digital Personal Data Protection (DPDP) Act, 2023, prioritizes government access for national security, creating a fundamental "adequacy gap."

- The EU is hesitant to grant India "Data Secure" status, crucial for high-value IT outsourcing, citing the lack of an independent regulator (India's Data Protection Board is government-appointed) and broad state surveillance exemptions.

- EU-India data cooperation is currently hindered by concerns over the broad exemptions granted to government agencies under Section 17 of India’s DPDP Act, 2023.

- This forces Indian IT firms to use costly Standard Contractual Clauses (SCCs), adding to their compliance costs for EU clients compared to the Philippines or Vietnam.

- Mobility Asymmetry- "Fortress Europe" vs. "Talent Export": While the EU seeks "circular migration" (temporary entry) strictly to fill its aging workforce gaps, India demands permanent and easier "Mode 4" access (movement of professionals) for its IT and healthcare workers.

- The divergence lies in the EU’s security-centric approach prioritizing the return of "illegal migrants" versus India’s economic approach, which views restrictive visa regimes and non-recognition of Indian degrees as a primary trade barrier.

- While the EU sets no official cap on Blue Cards, the 2026 mobility pact guarantees a minimum of 35,000 graduate permits against an annual target of 100,000 multi-year work visas for Indians.

- This guaranteed floor remains significantly below India’s vast supply of millions of graduates, creating a competitive bottleneck for those seeking formal entry.

- WTO Subsidy Wars- "Public Stockholding" Conflict: At the WTO, the EU alongside other developed nations like the US, aggressively challenges India’s Minimum Support Price (MSP) and food grain procurement as "trade-distorting" subsidies that breach the 10% limit, while simultaneously shielding its own farmers with massive "Green Box" (non-trade distorting) subsidies.

- For instance, at recent preparatory meetings for the 14th WTO Ministerial Conference (MC14) to be held in March 2026, the EU has proposed introducing “responsible consensus”, diluting the Most-Favoured-Nation (MFN) principle, restricting Special and Differential Treatment (S&DT) for developing countries, and deferring the restoration of a robust dispute settlement mechanism until core WTO reforms are completed.

- It is an approach that conflicts with India’s stance, which strongly supports the revival of a fair and effective multilateral dispute settlement system to safeguard developing-country interests.

- For instance, at recent preparatory meetings for the 14th WTO Ministerial Conference (MC14) to be held in March 2026, the EU has proposed introducing “responsible consensus”, diluting the Most-Favoured-Nation (MFN) principle, restricting Special and Differential Treatment (S&DT) for developing countries, and deferring the restoration of a robust dispute settlement mechanism until core WTO reforms are completed.

What Measures are Needed to Enhance India-EU Cooperation?

- Establishing a "Green Equivalence" Framework for CBAM: To defuse the carbon tax tension, both sides should negotiate a "Sovereign Carbon Credit Reciprocity" agreement where India’s domestic "Carbon Credit Trading Scheme" (CCTS)" is technically harmonized with the EU’s ETS.

- By validating Indian carbon certificates as "equivalent offsets" at the source, exporters can pay the carbon price domestically rather than to Brussels, ensuring the revenue remains within India for green transition funding while satisfying the EU’s requirement for a level playing field.

- Creating "GDPR-Aligned Data Enclaves" (Regulatory Sandboxes): To bypass the deadlock on national data adequacy, India should designate specific Special Economic Zones (like GIFT City) as "Data Adequacy Islands" that operate under stricter, GDPR-equivalent privacy norms independent of broader state surveillance laws.

- This "zonal adequacy" approach allows high-value data processing for EU clients to continue seamlessly within these ring-fenced enclaves, decoupling commercial data flow needs from the complex national security debates surrounding the DPDP Act.

- Operationalizing "Third-Market Co-Creation" in the Global South: To dilute the bilateral geopolitical fixation on Russia, the partnership should pivot to a "Joint Infrastructure Platform" for Africa and the Indo-Pacific, combining EU capital (Global Gateway) with India’s cost-effective execution capabilities.

- This "Strategic De-hyphenation" focuses energy on shared constructive goals like building resilient power grids in Kenya or digital payment systems in Vietnam creating a functional success track that insulates the broader relationship from specific diplomatic disagreements.

- A "Critical Raw Materials Club" with Value-Addition Guarantees: Rather than the EU simply extracting resources, a "Co-dependency Compact" should be signed where the EU transfers advanced metallurgical processing technology to India in exchange for secured lithium or rare earth supplies.

- This moves the relationship beyond a "buyer-seller" dynamic to a "joint-processor" alliance, ensuring India captures the high-value intermediate manufacturing stage while the EU secures a diversified supply chain free from Chinese monopoly.

- Establishing "India-EU Innovation Hubs" for Critical Technologies: As outlined in the Joint India-EU Comprehensive Strategic Agenda, both sides should operationalize dedicated "Innovation Hubs" to facilitate the co-development of critical and emerging technologies like 6G, Quantum Computing, and Advanced Semiconductors.

- This measure moves beyond simple "technology transfer" to a "co-creation" model where Indian design strengths (in AI and chip prototyping) are integrated with European research infrastructure, effectively building a democratic tech supply chain that serves as a resilient alternative to monopolistic global actors.

Conclusion:

The India–EU partnership is evolving from episodic engagement to strategic convergence, anchored in multipolarity, strategic autonomy, and rules-based order. The FTA acts as a catalyst, but the relationship now spans security, technology, climate governance, and human capital. Managing divergences through dialogue rather than coercion will be critical. Together, India and the EU can emerge as pillars of stability in a fractured global system.

|

Drishti Mains Question Discuss how the India–EU Free Trade Agreement reflects India’s evolving trade strategy in an era of supply-chain de-risking and green regulation. Examine its potential benefits and key implementation challenges. |

FAQs

1. Why is the India–EU partnership strategically important today?

It aligns two major democratic actors to promote strategic autonomy, multipolarity, and a rules-based global order amid great-power rivalry.

2. What makes the India–EU FTA a game-changer?

It grants preferential access to over 99% of Indian exports while embedding trade within technology, mobility, and climate cooperation.

3. How does the partnership address supply-chain risks?

Through de-risking from China, trusted manufacturing, and integration of Indian firms into EU-centric global value chains.

4. What is the main friction point in India–EU ties?

EU’s CBAM and regulatory standards, which India views as green protectionism impacting export competitiveness.

5. What is the way forward for India–EU relations?

Institutionalised dialogue on climate, data, mobility, and technology co-creation to convert divergences into convergence.

UPSC Civil Services Examination Previous Year Questions (PYQs)

Prelims:

Q. Consider the following statements: (2023)

The ‘Stability and Growth Pact’ of the European Union is a treaty that

- Limits the levels of the budgetary deficit of the countries of the European Union.

- Makes the countries of the European Union to share their infrastructure facilities

- Enables the countries of the European Union to share their technologies

How many of the above statements are correct

(a) Only one

(b) Only two

(c) All three

(d) None

Ans: (a)

Mains:

Q. The expansion and strengthening of NATO and a stronger US-Europe strategic partnership works well for India.' What is your opinion about this statement? Give reasons and examples to support your answer.