Supreme Court on Criminalisation of Politics | 11 Aug 2021

Why in News

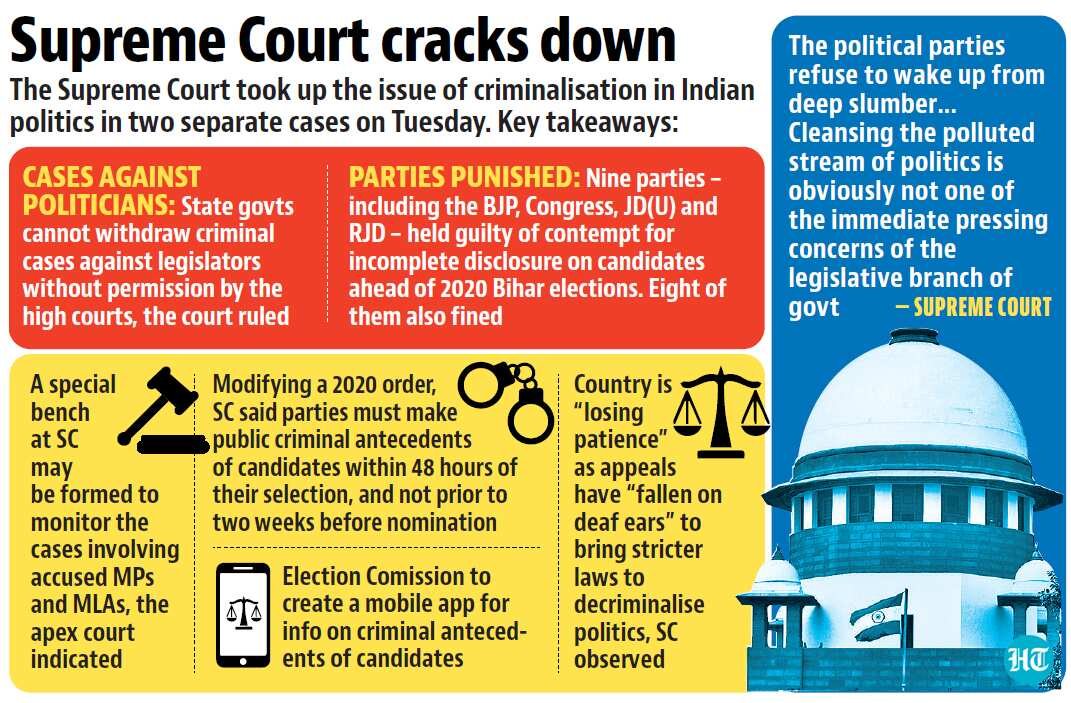

Recently, the Supreme Court in the two different judgements has raised concerns about the menace of criminalisation in politics.

- In one case, it found nine political parties guilty of contempt for not following in letter and spirit its February 13, 2020 direction.

- In another case, it has issued directions that no criminal case against MPs or MLAs can be withdrawn without an approval of the high court of the concerned state.

Key Points

- Case I: Political Parties Parties Penalised for Contempt:

- February 13, 2020 Order:

- The February 2020 order required political parties to publish details of criminal cases against its candidates on their websites, a local vernacular newspaper, national newspaper and social media accounts.

- This is to be done within 48 hours of candidate selection or not less than two weeks before the first date for filing of nominations, whichever is earlier.

- Supreme Court's Directive:

- The court took a lenient view of the matter, as it was the first elections (Bihar assembly Elections 2020) conducted after issuance of its directions.

- Directed political parties to have a caption “candidates with criminal antecedents candidates” on their homepages.

- It asked Election Commission of India (ECI) to create a dedicated mobile application containing information published by candidates regarding their criminal antecedents.

- The court appealed to the conscience of the lawmakers to come up with a law tackling the criminalization of politics.

- February 13, 2020 Order:

- Case II: Approval of High Court for Withdrawing Criminal Cases against MPs/MLAs:

- Background:

- The Bench was hearing a pending PIL (Public Interest Litigation) seeking establishment of fast-track courts for cases against legislators.

- In November 2017, the Supreme Court had ordered setting-up of Special Courts in each state to try the pending cases.

- Accordingly, 12 such courts were set up across the country.

- Supreme Court's Directive:

- Examine the withdrawals, whether pending or disposed of since last year.

- High court Chief Justices to constitute Special Benches to monitor the progress of criminal cases against sitting and former legislators.

- Judicial officers presiding over Special Courts or CBI Courts involving prosecution of MPs or MLAs shall not be transferred until further orders.

- Asked all the high courts to furnish details of posting of judges and the number of pending and disposed cases before them.

- Significance of the Judgment:

- It was a move that significantly clips the powers of the state governments at a time when the top court has expressed grave concern over the criminalisation of politics.

- Section 321 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973:

- Under this provision, the public prosecutor or assistant public prosecutor may, with the consent of the court, withdraw from the prosecution of a case at any time before the judgment is pronounced.

- Several states have withdrawn cases against legislators, under this section.

- Under this provision, the public prosecutor or assistant public prosecutor may, with the consent of the court, withdraw from the prosecution of a case at any time before the judgment is pronounced.

- Background:

Criminalisation of Politics

- About:

- It means the participation of criminals in politics which includes that criminals can contest in the elections and get elected as members of the Parliament and the State legislature.

- It takes place primarily due to the nexus between politicians and criminals.

- Reasons:

- Lack of Political Will:

- In spite of taking appropriate measures to amend the Representation of the People Act, 1951 there has been an unsaid understanding among the political parties which deters Parliament to make strong law curbing criminalisation of politics.

- Lack of Enforcement:

- Several laws and court judgments have not helped much, due to the lack of enforcement of laws and judgments.

- Narrow Self-interests:

- Publishing of the entire criminal history of candidates fielded by political parties may not be very effective, as a major chunk of voters tend to vote through a narrow prism of community interests like caste or religion.

- Use of Muscle and Money Power:

- Candidates with serious records seem to do well despite their public image, largely due to their ability to finance their own elections and bring substantive resources to their respective parties.

- Also, sometimes voters are left with no options, as all competing candidates have criminal records.

- Lack of Political Will:

- Effects:

- Against the Principle of Free and Fair Election:

- It limits the choice of voters to elect a suitable candidate.

- It is against the ethos of free and fair election which is the bedrock of a democracy.

- Affecting Good Governance:

- The major problem is that the law-breakers become law-makers, this affects the efficacy of the democratic process in delivering good governance.

- These unhealthy tendencies in the democratic system reflect a poor image of the nature of India’s state institutions and the quality of its elected representatives.

- Affecting Integrity of Public Servants:

- It also leads to increased circulation of black money during and after elections, which in turn increases corruption in society and affects the working of public servants.

- Causes Social Disharmony:

- It introduces a culture of violence in society and sets a bad precedent for the youth to follow and reduces people's faith in democracy as a system of governance.

- Against the Principle of Free and Fair Election:

Landmark Decisions in Decriminalising Politics

- In 2002, the Supreme Court, in Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR) v. Union of India, mandated the disclosure of information relating to criminal antecedents, educational qualification, and personal assets of a candidate contesting elections.

- The Supreme Court in Lily Thomas v. Union of India (2013) case, struck down as unconstitutional Section 8(4) of the Representation of the People Act that allowed convicted lawmakers a three-month period for filing appeal to the higher court and to get a stay on the conviction and sentence.

- In People’s Union for Civil Liberties v. Union of India (2013), the SC recognised negative voting as a constitutional right of a voter and directed the Government to provide the ‘NOTA’ option in electronic voting machines.

- In Public Interest Foundation and Ors. v Union of India (2014) based on recommendations made by the Law Commission in its 244th report, the SC had ordered that trials, in relation to sitting MPs and MLAs be concluded within a year of charges against them being framed.

- The Supreme Court’s decision on information disclosure (Lok Prahari v. Union of India, 2018) paves a way for future constitutional interventions in India’s political party funding regime, including the scheme of electoral bonds.

Way Forward

- The nature of the government machinery needs to change to make it more transparent, accountable and pervade.

- Awareness among people (voters) about their rights and they should vote for the right person should be created.

- Given the reluctance by the political parties to curb criminalisation of politics and its growing detrimental effects on Indian democracy, Indian courts must now seriously consider banning people accused with serious criminal charges from contesting elections.