Climate Change and Ocean Currents | 23 Sep 2019

A new study suggests a link between Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) and the Indian Ocean.

- For thousands of years, Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) has remained stable but in the last 15 years, signs show that AMOC may be slowing, which could have drastic consequences on the global climate.

- However, the rising temperatures in the Indian Ocean can help to boost the AMOC and delay slow down.

- Warming in the Indian Ocean generates additional precipitation, which, in turn, draws more air from other parts of the world, including the Atlantic.

- With so much precipitation in the Indian Ocean, there will be less precipitation in the Atlantic Ocean.

- Lesser precipitation leads to higher salinity in the waters of the tropical portion of the Atlantic — because there won’t be as much rainwater to dilute it.

- This saltier water in the Atlantic, as it comes north via AMOC, will get cold much quicker than usual and sink faster.

- The above process would act as a jump start for AMOC, intensifying the circulation.

- But if other tropical ocean’s warming, especially the Pacific's, catches up with the Indian Ocean, the advantage of intensification for AMOC may stop.

- Moreover, it isn't clear whether the slowdown of AMOC is caused by global warming alone or it is a short-term anomaly related to natural ocean variability.

- Slow down of AMOC had taken place 15,000 to 17,000 years ago which caused harsh winters in Europe, with more storms or a drier Sahel in Africa due to the downward shift of the tropical rain belt.

- Alternating oceanic system patterns like ENSO also affects rainfall distribution in the tropics and can have a strong influence on weather in other parts of the world.

Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC)

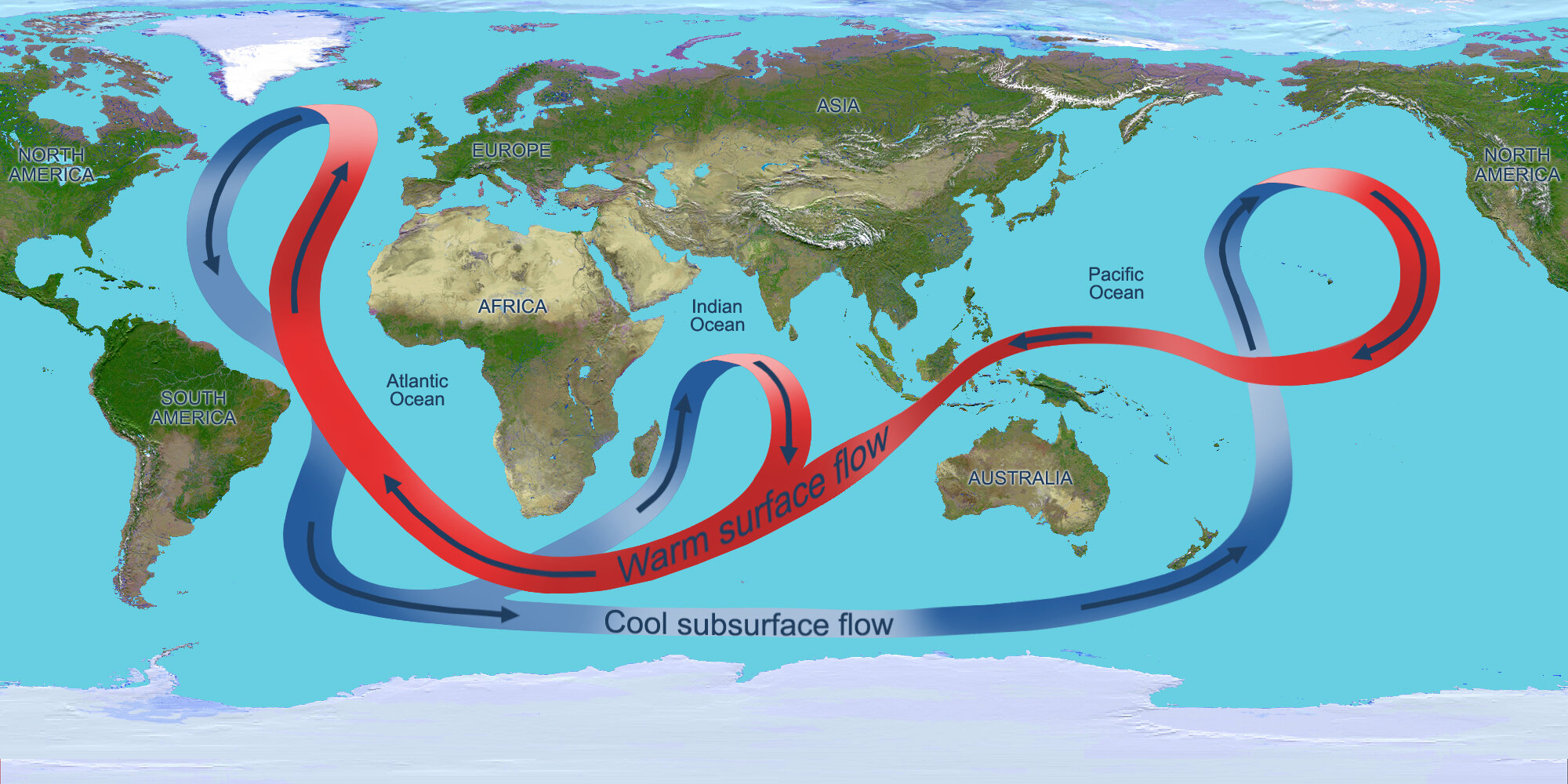

- Atlantic meridional overturning circulation (AMOC) — which is sometimes referred to as the “Atlantic conveyor belt” — is one of the Earth’s largest water circulation systems where ocean currents move warm, salty water from the tropics to regions further north, such as western Europe and sends colder water south.

- As warm water flows northwards in the Atlantic, it cools, while evaporation increases its salt content.

- Low temperature and high salt content increases the density of the water, causing it to sink deep into the ocean.

- The cold, dense water deep below slowly spreads southward.

- Eventually, it gets pulled back to the surface and warms again, and the circulation is complete.

- This continual mixing of the oceans and the distribution of heat and energy around the planet contributes to the global climate.

- Atlantic Meridional Overturning Current (AMOC) ensures the oceans are continually mixed, and heat and energy are distributed around Earth.

El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO)

- It involves temperature changes of 1°-3°C in the central and eastern tropical Pacific Ocean, over periods between three and seven years.

- El Niño refers to the warming of the ocean surface and La Niña to cooling, while “Neutral” is between these extremes.