Child Adoption in India | 12 Apr 2022

For Prelims: Adoption (First Amendment) Regulations, 2021, CARA.

For Mains: Child Adoption in India and related issues, Issues Related to Children.

Why in News?

Recently, the Supreme Court agreed to hear a plea seeking to simplify the legal process for child adoption in India.

- In 2021, Adoption (First Amendment) Regulations, 2021 was notified which allowed Indian diplomatic missions abroad to be in charge of safeguarding adopted children whose parents move overseas with the child within two years of adoption.

What are the Issues Related to Child Adoption in India?

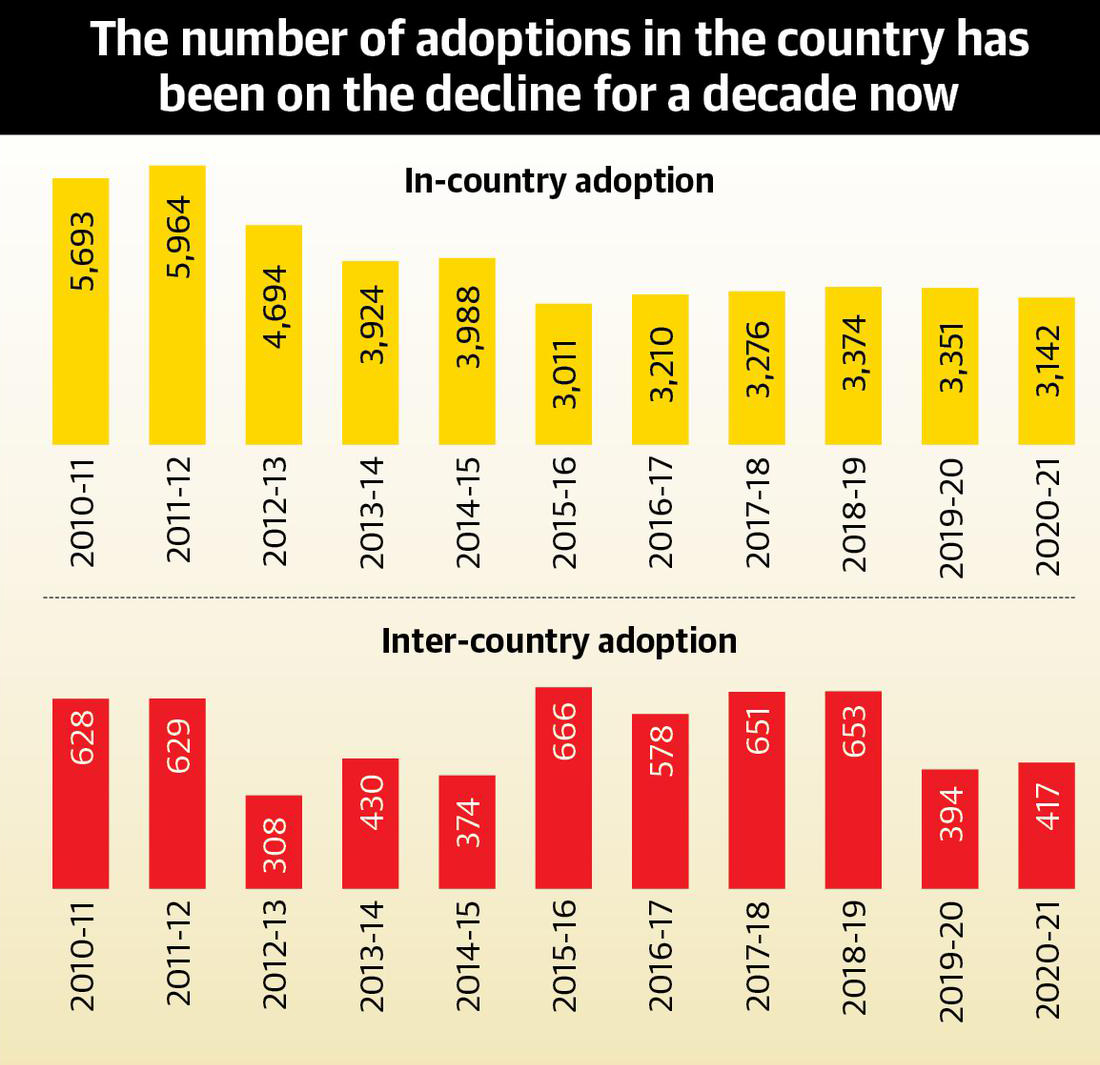

- Declining Statistics and Institutional Apathy:

- There is a wide gap between adoptable children and prospective parents, which may increase the length of the adoption process.

- Data shows that while more than 29,000 prospective parents are willing to adopt, just 2,317 children are available for adoption.

- Returning Children after Adoption:

- Between 2017-19, the Central Adoption Resource Authority (CARA) faced an unusual upsurge in adoptive parents returning children after adopting.

- Central Adoption Resource Authority (CARA) is a statutory body of the Ministry of Women & Child Development. It functions as the nodal body for adoption of Indian children and is mandated to monitor and regulate in-country and inter-country adoptions.

- According to the data, 60% of all children returned were girls, 24% were children with special needs, and many were older than six.

- The primary reason these ‘disruptions’ occur is that disabled children and older children take much longer to adjust to their adoptive families.

- This is primarily because older children find it challenging to adjust to a new environment because institutions do not prepare or counsel children about living with a new family.

- Between 2017-19, the Central Adoption Resource Authority (CARA) faced an unusual upsurge in adoptive parents returning children after adopting.

- Disability and Adoption:

- Only 40 children with disabilities were adopted between 2018 and 2019, accounting for approximately 1% of the total number of children adopted in the year.

- Annual trends reveal that domestic adoptions of children with special needs are dwindling with each passing year.

- Manufactured Orphans and Child Trafficking:

- In 2018, Ranchi’s Mother Teresa’s Missionaries of Charity came under fire for its “baby-selling racket” after a nun from the shelter confessed to selling four children.

- Similar instances are becoming increasingly common as the pool of children available for adoption shrinks and waitlisted parents grow restless.

- Also, during the pandemic, cases of threat of child trafficking and illegal adoption rackets came into play.

- These rackets usually source children from poor or marginalised families, and unwed women are coaxed or misled into submitting their children to trafficking organisations.

- In 2018, Ranchi’s Mother Teresa’s Missionaries of Charity came under fire for its “baby-selling racket” after a nun from the shelter confessed to selling four children.

- LGBTQ+ Parenthood and Reproductive Autonomy:

- Despite the constant evolution of the definition of a family, the ‘ideal’ Indian family nucleus still constitutes a husband, a wife and daughter(s) and son(s).

- In February 2021, while addressing petitions seeking the legal recognition of LGBTQI+ marriages, the government opined that LGBTQI+ relationships could not be compared to the “Indian family unit concept” of a husband, wife and children.

- The invalidity of LGBTQI+ marriages and relationships in the eyes of the law obstructs LGBTQI+ persons from becoming parents because the minimum eligibility for a couple to adopt a child is the proof of their marriage.

- To negotiate these unfavourable legalities, illegal adoptions are becoming increasingly common among queer communities.

- Moreover, provisions under the Surrogacy (Regulation) Bill, 2020 and Assisted Reproductive Technology (Regulation) Bill, 2020 completely exclude LGBTQI+ families, stripping them of their reproductive autonomy.

- Despite the constant evolution of the definition of a family, the ‘ideal’ Indian family nucleus still constitutes a husband, a wife and daughter(s) and son(s).

What are the Laws to Adopt a Child in India?

- The adoption in India takes place under Hindu Adoptions and Maintenance Act, 1956 (HAMA) and the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2015 (JJ Act).

- HAMA, 1956 falls in the domain of Ministry of Law and Justice and JJ Act, 2015 pertains to the Ministry of Women and Child Development.

- As per the government rules, Hindus, Buddhists, Jains, and Sikhs are legalized to adopt kids.

- Until the JJ Act, the Guardians and Ward Act (GWA), 1980 was the only means for non-Hindu individuals to become guardians of children from their community.

- However, since the GWA appoints individuals as legal guardians and not natural parents, guardianship is terminated once the ward turns 21 and the ward assumes individual identity.

Way Forward

- Need to Prioritise Children’s Welfare:

- The primary purpose of giving a child in adoption is his welfare and restoring his or her right to family.

- CARA and the ministry must accord attention to the vulnerable and invisible community of children silently suffering in our institutions.

- Need to Strengthen the Institutional Mandates:

- The adoption ecosystem needs to transition from a parent-centric perspective to a child-centric approach.

- Need to Adopt an Inclusive Approach:

- There is a need to adopt an inclusive approach that focuses on the needs of a child to create an environment of acceptance, growth, and well being, thus recognising children as equal stakeholders in the adoption process.

- Adoption Process Needs to Simplified:

- The process of adoption needs to be simplified by taking a close relook at the various regulations guiding the procedure of adoption.

- The ministry can engage with concerned experts working in this field to get feedback on the practical difficulties which prospective parents are facing.