India’s Nutritional Security Push

This editorial is based on “Addressing nutrition along with hunger: Funding and policy push vital” which was published in The Business Standard on 15/02/2026. This editorial examines India’s transition from food security to nutritional security, highlighting persistent deficits in micronutrients, maternal and child health, and diet diversity despite expansive welfare schemes. It argues that sustained funding, policy convergence, and nutrition-centric agriculture are vital to secure India’s future human capital.

For Prelims: Poshan Abhiyaan, Poshan Tracker,One Nation One Ration Card, Climate-Smart Agriculture.

For Mains: Current status of nutritional security in India, Key development , Issues associated with nutritional security, measures needed to achieve nutritional security.

While the Green Revolution successfully decoupled India from the threat of mass starvation, it inadvertently prioritized caloric quantity over nutritional quality. Today, the nation faces a "hidden hunger" where staple-heavy diets provide sufficient energy but lack the critical micronutrients necessary for healthy development. Shifting the focus from food security to nutritional security is no longer a choice but a biological imperative to improve the productivity and health of India's future human capital.

What is the Current Status of Nutritional Security in India?

- Undernourishment & Hunger

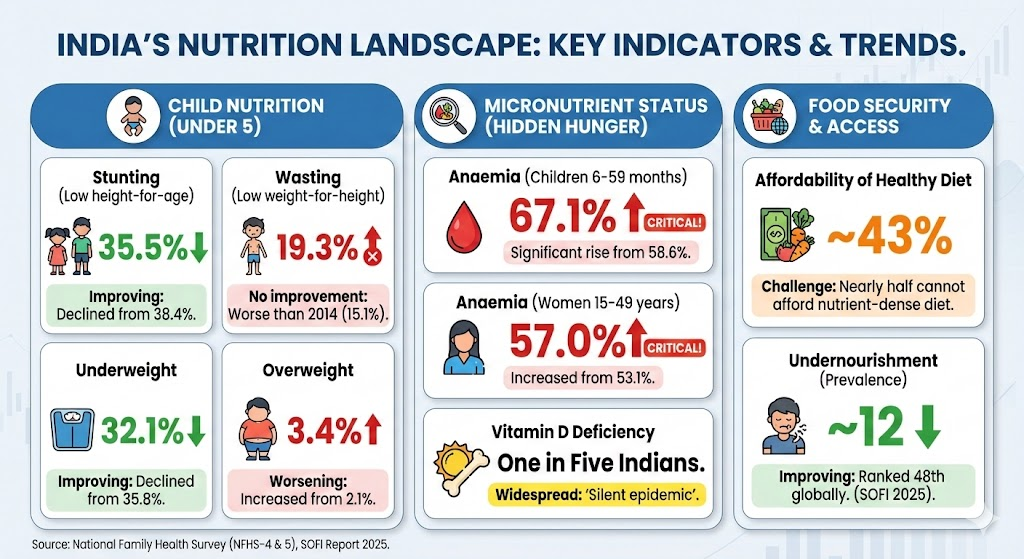

- About ~12% of India’s population remains undernourished (~172 million people), a significant reduction from past years but still large.

- India ranks low on the Global Hunger Index (GHI 2025) around 102th out of 123 countries with a “serious” level of hunger.

- Child Malnutrition

- According to recent estimates:

- Stunting (low height-for-age): ~35% of under-5 children, indicates chronic undernutrition.

- Wasting (low weight-for-height): 18.7% , one of the highest in the world, signaling acute malnutrition.

- Overweight/obesity among children is also rising, a sign of the double burden of malnutrition.

- According to recent estimates:

- Micronutrient Deficiencies

- Anaemia is widespread, especially among women and young children:

- 67.1% of children and 59.1% of adolescent girls in India are anemic (NFHS-5).

- High rates of micronutrient deficiency (iron, zinc, vitamin A etc.) indicate hidden hunger, where caloric needs are met but essential micronutrients are lacking.

- Anaemia is widespread, especially among women and young children:

- Diet Quality & Affordability

- 40.4% of people cannot afford a healthy diet (as of 2024- State of Food and Nutrition in the World’ (SOFI) 2025 report), food price inflation makes nutrient-rich diets expensive.

- Many households can access calories through subsidised grains, but quality nutrition (proteins, fruits, vegetables, micronutrients) remains out of reach for large sections.

What are the Key Developments in India’s Shift Towards Nutritional Security?

- Shift to "Genetic" Nutrition: The agricultural paradigm is decisively shifting from "caloric sufficiency" to "nutrient density," using bio-fortified crops to passively deliver micronutrients like Zinc and Iron to the population without requiring behavioral changes in diet.

- For instance, ICAR has developed over 150 biofortified varieties. The biofortified varieties are 1.5 to 3.0 times more nutritious than the traditional varieties.

- For instance, the rice variety CR DHAN 315 has excess zinc, the Wheat variety HD 3298 is enriched with protein and iron. The Pusa Mustard 32 is enriched with low Araucic Acid, while Girnar 4 and 5 varieties of Peanuts are rich in increased Oleic Acid.

- Universal Rice Fortification: The "Rice Fortification" push has matured from a pilot scheme to a nationwide safety net, effectively turning the Public Distribution System (PDS) into a massive vehicle for delivering iron, folic acid, and Vitamin B12 to the poorest demographics.

- 100% of the custom-milled rice (CMR) supplied to the Central Pool by the Food Corporation of India (FCI) and state agencies is now fortified.

- A notable efficacy study in the Chandauli (an aspirational district of Uttar Pradesh) showed a 7.5% reduction in anemia levels following the consistent supply of fortified rice.

- Poshan Tracker" & Digital Governance: The governance of nutrition has moved from manual registers to real-time algorithmic auditing, where the Poshan Tracker app now closes the "delivery gap" by tracking actual consumption rather than just distribution at Anganwadis.

- For last mile tracking of service delivery, Facial Recognition System (FRS) has been introduced in Poshan Tracker app for distribution of Take-Home Ration to ensure that benefit is given only to the intended beneficiary registered in Poshan Tracker.

- Mainstreaming "Shree Anna": Post-International Year of Millets (IYOM) 2023, policy incentives have successfully integrated climate-resilient millets into the state procurement basket, addressing the "diabetes-malnutrition" double burden by replacing refined carbohydrates with high-fiber, mineral-rich alternatives.

- For example, Odisha has integrated millet laddus into mid-day meals.

- Moreover, for the Kharif Marketing Season (KMS) 2025-26, the MSP for Jowar (Hybrid) was increased by ₹328 per quintal. Further, Ragi saw one of the highest absolute increases in MSP for the 2025-26 season, rising by ₹596 per quintal.

- Increased Focus on The "First 1000 Days" Interventions have become hyper-targeted towards the critical "conception-to-age-two" window, recognizing that stunting (32.9%) is largely irreversible after this period,this shifts strategy to Conditional Cash Transfers (CCTs) linked strictly to Antenatal Care (ANC) and immunization compliance to ensure early health tracking..

- PMMVY 2.0 coverage expanded to the second child (if a girl) with higher cash transfers (₹6,000).

- Also, Under Mission Poshan 2.0, 2 lakh Anganwadi Centres located in Government buildings are to be strengthened as Saksham Anganwadis for delivery of improved nutrition and for Early Childhood Care and Education in the 15th Finance Commission cycle.

- Climate-Smart Nutritional Security: Recognizing that rising CO2 levels reduce the nutrient density of staple crops, the new agricultural roadmap prioritizes "nutrition-per-drop" and heat-tolerant varieties to prevent a collapse in dietary quality due to climate stress.

- To strengthen nutritional security, the National Mission on Natural Farming has been rolled out across 17,267 clusters covering 8.52 lakh hectares (January 2025), with a focus on pulse cultivation in rainfed areas to ensure protein availability amid erratic monsoons.

- Tackling "Hidden Hunger" via Social Audit: The "Jan Andolan" (People's Movement) strategy has decentralized accountability, empowering "Poshan Panchayats" to conduct social audits and manage localized nutritional gardens to supplement carb-heavy rations with fresh micronutrients.

- Under nutrition-focused interventions, more than 4 lakh Poshan Vatikas (Nutri-gardens) have been established at Anganwadis (March 2023), with rural pilot areas reporting higher green leafy vegetable intake among pregnant women.

- Addressing the "Double Burden": Nutritional policy has broadened to tackle the simultaneous crisis of undernutrition and obesity/NCDs, with FSSAI implementing aggressive "Front-of-Pack Labeling" (FOPL) to discourage consumption of ultra-processed foods.

- Also, recently the Supreme Court has urged FSSAI to examine the introduction of mandatory front-of-package warning labels (FOPL) on packaged foods high in sugar, salt, and saturated fats.

- The Court emphasized that such regulatory steps are necessary to protect citizens’ right to health.

- One Nation One Ration Card (ONORC): The ONORC platform has dissolved geographical barriers to food access, acting as the single most critical nutritional safety net for the 450 million migrant workforce who historically faced starvation during transit or migration.

- Demonstrating the scale of food security portability, over 197 crore transactions have been recorded under the scheme since 2019 (as of December 2025).

- PM-JANMAN-Reaching the "Last Mile" (Tribal Nutrition): Targeting the most marginalized, PM-JANMAN focuses on Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups (PVTGs), acknowledging that standard coverage often misses remote habitations, it creates a saturation model ensuring basic nutritional infrastructure (Anganwadis) reaches these isolated hamlets first.

- Under PM JANMAN for the targeted development of 75 Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups (PVTGs), a total of 2,500 Anganwadi Centres (AWCs) has been sanctioned for construction across the country.

What are the Key Issues Associated with Nutrition Security in India?

- The "Calorie-Nutrient" Mismatch: India’s food system suffers from a "Green Revolution hangover," still to an extent prioritizing caloric sufficiency (yields) over nutrient density, leading to a population that is "full but malnourished" due to micronutrient-deficient staple grains.

- India's safety net is heavily skewed towards carbohydrate-rich cereals (Rice/Wheat) at the expense of proteins and pulses, failing to provide a balanced "thali" necessary to combat muscle wasting and cognitive deficits.

- A recent nationwide survey revealed a significant nutritional crisis: nearly 60% of urban Indians suffer from Protein Deficiency.

- The Economic Survey 2026 highlights the need for greater awareness regarding health supplements and raises concerns over the increasing prevalence of lifestyle diseases linked to nutritional deficiencies.

- India's safety net is heavily skewed towards carbohydrate-rich cereals (Rice/Wheat) at the expense of proteins and pulses, failing to provide a balanced "thali" necessary to combat muscle wasting and cognitive deficits.

- Persistent Child Stunting & Wasting: Structural malnutrition remains dangerously high due to intergenerational poverty and poor maternal health, creating a cycle where undernourished mothers birth undernourished children, stalling human capital development.

- Despite extensive food security measures, GHI 2025 ranks India 102nd, underscoring continuing nutritional deficits.

- The high prevalence of stunting and wasting among under-5 children places the country in the “serious” hunger category.

- The Anemia Burden in Women: Gender-based nutritional inequality persists, with women eating "last and least," leading to chronic iron deficiency that directly impacts productivity and newborn health, resisting decades of supplementation programs.

- Malnutrition remains rampant among lactating mothers, with over 50% of women of reproductive age still anemic, highlighting that biofortified crop introductions have yet to translate into broad nutritional gains.

- Slow Adoption of Biofortified Crops: Despite the development of nutrient-rich seeds (Iron-Pearl Millet, Zinc-Wheat), the "lab-to-land" transfer is sluggish because farmers prioritize older, high-yield varieties without guaranteed premium pricing for nutritional quality.

- Although 100+ biofortified varieties are released, they still cover a minority of total acreage. Further widely grown commercial crops still lack essential micronutrients.

- Climate Change Impact on Nutrient Quality: Rising atmospheric CO2 and temperature stress are actively reducing the protein, iron, and zinc content of staple crops, meaning the same quantity of food now delivers less nutrition than it did decades ago.

- A recent study suggests that rising CO₂ levels could lower the protein content in rice by about 10% and reduce its iron levels by nearly 8%.

- Economic Inaccessibility of "Protective Foods": While staples are subsidized, inflation in "protective foods" (eggs, vegetables, fruits) puts a diverse diet out of reach for the working poor, forcing reliance on cheap, empty calories.

- Even as cereals are subsidised, inflation in protective foods like eggs, fruits and vegetables has made balanced diets unaffordable for the working poor, pushing households toward cheap, calorie-dense but nutrient-poor foods.

- A critical lack of cold chain infrastructure causes a significant portion of India’s horticulture produce to rot before reaching the consumer, keeping nutrient-dense fruits and vegetables artificially expensive and inaccessible to the poor, effectively nullifying gains in production.

- The Rising "Double Burden": India is simultaneously battling malnutrition and rising obesity/non-communicable diseases (NCDs) as urbanization shifts diets toward processed, sugar-heavy foods before undernutrition is fully eradicated.

- NCDs such as cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, cancer, and chronic respiratory ailments now account for nearly 63–65% of all deaths in India

- Urban slums show paradoxical trends where stunting coexists with obesity in the same households due to poor-quality, energy-dense but nutrient-poor processed food consumption.

- Policy Implementation Gaps: Nutrition demands a "convergence" approach (Sanitation + Health + Food), but silos between ministries and leakage in delivery mechanisms dilute the impact of well-intentioned schemes like Poshan Abhiyaan.

- Nutritional intake is often nullified by poor Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene (WASH) which causes Environmental Enteropathy (gut dysfunction), this prevents nutrient absorption, meaning "feeding" programs fail to "nourish" because the child’s compromised gut constantly leaks nutrients.

- Antibiotic Resistance (AMR)- The "Gut Health" Sabotage: The rampant, unregulated use of growth-promoting antibiotics in the Indian poultry and dairy sectors is breeding drug-resistant bacteria that enter the human gut through food, causing dysbiosis (gut imbalance) that physically prevents the absorption of nutrients, rendering good diets ineffective.

- For instance, a study conducted by researchers at Kerala Veterinary University found a significant presence of antimicrobial-resistant (AMR) Escherichia coli (E. coli) in chicken samples collected from six districts of the state.

- Lack of Nutritional Awareness & Dietary Diversity: Cultural habits and a lack of nutritional literacy lead to poor dietary choices even among those who can afford better, with a heavy reliance on monotonous diets lacking in fruits, vegetables, and coarse grains.

- Aggressive marketing of ultra-processed foods and rising urban lifestyles have further shifted consumption patterns toward calorie-dense but nutrient-poor diets.

- Inadequate emphasis on locally available, seasonal, and traditional foods has also weakened dietary diversity, aggravating hidden hunger and micronutrient deficiencies.

What Measures are Needed to Strengthen Nutritional Security in India?

- Nutrition-Linked Minimum Support Price (MSP): To make nutrition economically viable for farmers, the agricultural procurement policy must transition to a "Nutrition-Linked MSP" structure.

- By offering a distinct price premium for biofortified varieties (like High-Zinc Wheat or Iron-Pearl Millet) over conventional grains, the state can naturally incentivize the shift from "volume-centric" to "quality-centric" farming.

- This ensures that the Public Distribution System (PDS) becomes passively enriched with essential micronutrients without requiring complex post-harvest fortification logistics.

- Decentralized "Nutri-Basket" Procurement: The PDS needs to evolve from a centralized cereal silo into a localized "Nutri-Basket" system that mandates the inclusion of regionally relevant coarse grains and pulses.

- Empowering districts to procure and distribute local superfoods (like Ragi in the south or Bajra in the west) drastically reduces the carbon footprint of logistics while ensuring beneficiaries receive culturally palatable, high-fiber diets that actively combat the rising incidence of diabetes and obesity among the poor.

- Convergence for the "First 1000 Days": Interventions must rigorously enforce a "Lifecycle Convergence Framework" that integrates maternal health, sanitation (WASH), and immunization into a single delivery vertical for the critical conception-to-age-two window.

- Legally linking maternity entitlements to antenatal nutrition compliance and exclusive breastfeeding milestones shifts the paradigm from treating malnourished children to preventing "intrauterine growth restriction," thereby arresting stunting before a child is even born.

- Dynamic "Hotspot" Targeting via AI: Leveraging India’s Digital Public Infrastructure, the administration should utilize AI-driven analytics on Poshan Tracker data to identify real-time "Nutritional Hotspots" instead of relying on lagging survey data.

- This allows for the surgical, dynamic allocation of supplementary nutrition and medical officers to specific high-burden blocks or slums, ensuring that fiscal resources are concentrated on the most vulnerable demographics before acute malnutrition becomes irreversible.

- Community-Led Social Audits: To plug leakage and ensure quality, the governance of Anganwadis must be democratized through "Community-Led Social Audits" empowered by local Self-Help Groups (SHGs).

- Transforming nutrition from a bureaucratic deliverable into a community-owned asset ensures that funds for supplementary nutrition are actually spent on milk and eggs, while fostering a bottom-up culture of accountability where the village itself monitors the growth charts of its children.

- Mandatory "Passive Fortification" Standards: Regulatory bodies must aggressively enforce "Mandatory Fortification Standards" for open-market essentials like edible oil, milk, and salt to create a passive immunity shield for the urban poor who fall outside the PDS net.

- By collaborating with the private sector to standardize micronutrient premixes and subsidizing compliance costs for MSMEs, the state ensures that even non-subsidized, daily-wage food purchases contribute to lifting the national baseline of Vitamin A and D levels.

- Climate-Resilient "Agro-Nutritional" Zones: Agricultural planning must pivot towards establishing "Agro-Nutritional Zones" that align crop patterns with local ecological carrying capacity to prevent the "Nutrient Dilution" effect caused by rising carbon dioxide levels.

- This ensures sustainable food production that does not compromise on nutritional quality, safeguarding future generations against the "hidden hunger" exacerbated by climate change while simultaneously reducing water and fertilizer dependence.

- Urban "Migrant-Specific" Nutrition Corridors: Recognizing the unique nutritional vulnerability of India’s transient workforce, the "One Nation One Ration Card" (ONORC) must be expanded into "Urban Nutrition Corridors" that offer subsidized, energy-dense cooked meals.

- Establishing "Community Kitchens" at major industrial clusters ensures that migrant laborers, who often lack access to cooking fuel and potable water, receive adequate calories and protein without relying on unsafe street food.

- Behavioral "Nudging" via SBCC: A sustained "Social and Behavioural Change Communication" (SBCC) campaign is essential to dismantle dietary myths and promote the consumption of diverse, locally available "protective foods" over aspirational processed goods.

- Integrating nutritional literacy into school curricula creates a demand-side pull for healthy eating, ensuring that increased purchasing power translates into improved nutritional outcomes rather than just higher consumption of refined carbohydrates.

- "One Health" Zoonotic Surveillance: Adopting a "One Health" Framework is crucial to monitor and control the quality of animal-source foods (milk, eggs, meat), which are vital for combating protein deficiency in a vegetarian-dominant society.

- Strengthening veterinary services ensures that the livestock sector delivers safe, high-protein nutrition without introducing zoonotic diseases or antibiotic residues into the human food chain, thereby protecting both nutritional status and public health safety.

Conclusion

India’s nutritional challenge today is not scarcity of food, but scarcity of quality nutrition. Despite robust safety nets like PDS and PM-GKAY, high stunting, wasting, and anemia reveal deep structural and dietary gaps. Recent policy shifts toward biofortification, millets, digital governance, and first-1000-days interventions mark a decisive course correction. Achieving this is a prerequisite to fulfilling SDG 2 (Zero Hunger), specifically Target 2.2, which mandates ending all forms of malnutrition by 2030.

|

Drishti Mains Question Despite large-scale welfare schemes, India continues to face high levels of child stunting and anemia. Analyze the structural causes and suggest solutions. |

FAQs

1. What is hidden hunger?

Adequate calories but deficiency of essential micronutrients.

2. Why are millets promoted for nutrition?

They are climate-resilient and rich in fiber and minerals.

3. What is the first 1000 days approach?

Nutrition focuses from conception to two years of age.

4. Why is anemia persistent in India?

Gender inequality, poor diet diversity, and low absorption.

5. What role does PDS play in nutrition?

Ensures calorie access but remains cereal-centric.

UPSC Civil Services Examination, Previous Year Question (PYQ)

Prelims

Q1. In the context of India’s preparation for Climate-Smart Agriculture, consider the following statements: (2021)

- The ‘Climate-Smart Village’ approach in India is a part of a project led by the Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS), an international research programme.

- The project of CCAFS is carried out under Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) headquartered in France.

- The International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT) in India is one of the CGIAR’s research centres.

Which of the statements given above are correct?

(a) 1 and 2 only

(b) 2 and 3 only

(c) 1 and 3 only

(d) 1, 2 and 3

Ans: (d)

Q2. With reference to the provisions made under the National Food Security Act, 2013, consider the following statements: (2018)

- The families coming under the category of ‘below poverty line (BPL)’ only are eligible to receive subsidised food grains.

- The eldest woman in a household, of age 18 years or above, shall be the head of the household for the purpose of issuance of a ration card.

- Pregnant women and lactating mothers are entitled to a ‘take-home ration’ of 1600 calories per day during pregnancy and for six months thereafter.

Which of the statements given above is/are correct?

(a) 1 and 2 only

(b) 2 only

(c) 1 and 3 only

(d) 3 only

Ans: (b)